Several nuclear and thermal power units are currently offline as a result of the recent earthquake and subsequent events. As of late March 2011, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) had a supply capacity of only 38.5 million kilowatts. Calls to conserve energy in homes and offices spread soon after the earthquake, but on March 14 TEPCO began implementing rolling blackouts as an additional measure. A tightrope situation continues nonetheless, with the minister of economy, trade, and industry warning on March 17 of a possible large-scale power outage taking place that evening.

Expected Shortage Levels

Media reports suggest that the rolling blackouts may be temporarily called off around the end of April. But there will no escaping higher electricity demand than current levels in the summer, and stopgap measures will be needed to make it through the summer months.

What, then, will be the extent of the power shortage in the summer?

Peak demand in the TEPCO service area during the scorching summer of 2010 was 60 million kilowatts; in an average summer the figure is about 55 million kilowatts. Supply, meanwhile, is estimated to total no more than about 45 million kilowatts, even counting the thermal power units that are currently shut down due to the disaster or regular inspection. This means that, depending on summer weather conditions, a supply-demand gap of between 10 million and 15 million kilowatts could arise.

According to the media, TEPCO anticipates a shortage of 8.5 million kilowatts, whereas the government gives a somewhat more pessimistic shortfall estimate of around 10 million kilowatts. The March 25 issue of the daily Nihon Keizai Shimbun stated that TEPCO has a plan to augment its capacity by over 10 million kilowatts by newly constructing LNG-fueled thermal power units. But the new units will not go into operation until the winter at the earliest, and on March 28 the Sankei Shimbun pointed out that factories needed for the construction of these units were damaged in the quake and tsunami.

Actual Power Usage

Energy demand by use in the TEPCO service area is as shown in Table 1. About 34% of the total is used by households (given as “lighting” in the table), 31% by offices (“power” and “commercial power”), and 34% by industry (“industrial power”). Even if electricity use is cut down in the industrial sector—to which the large-demand customers belong—by such means as limiting total consumption and shifting to nighttime operations, reductions by offices and households will still be needed.

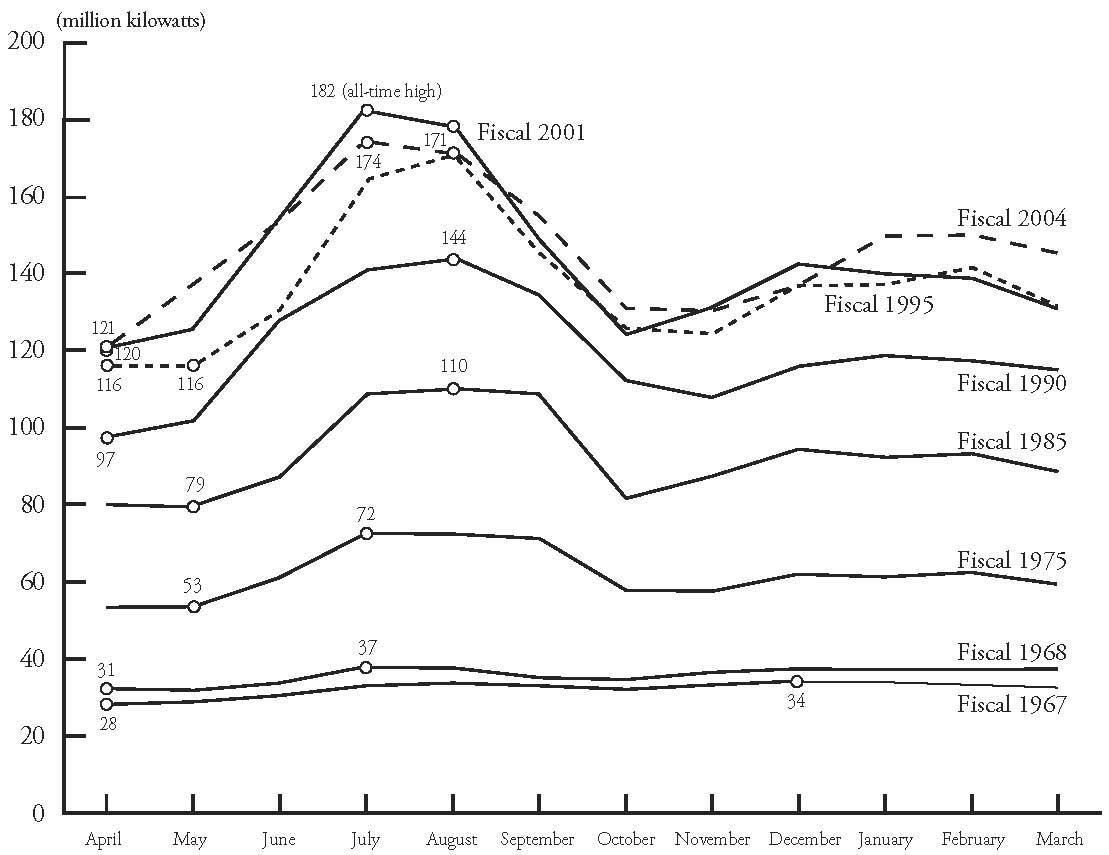

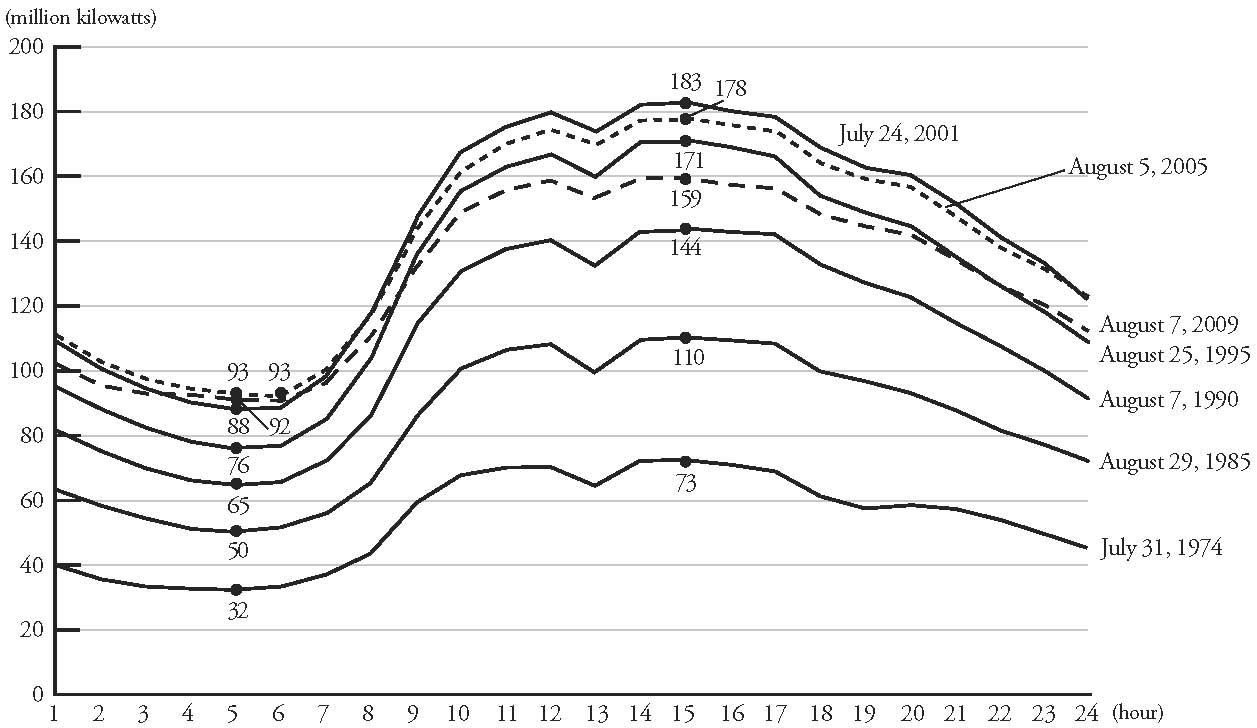

As seen in Figure 1, energy demand peaks in the summer months from June to September, especially July and August. Figure 2 indicates that energy use soars from around 8 am, remains high between 10 am and 6 pm, and gradually decreases thereafter, returning to the 8 am level by around midnight.

If energy use is to be cut back to 45 million kilowatts—compared to 60 million kilowatts last year—the key will be measures to reduce consumption during the peak hours of 9 am to 9 pm from June to August.

Table 1. Energy Demand by Use in the TEPCO Service Area

(billion kilowatt-hours)

| Type of use | Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2008 | Fiscal 2007 | Fiscal 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other than eligible customers | Lighting | 96.09 | 96.06 | 97.60 | 93.21 |

| Power | 11.39 | 11.91 | 12.78 | 12.63 | |

| Lighting and power total | 107.48 | 107.96 | 110.39 | 105.84 | |

| Eligible customers | Commercial power | 76.54 | 77.45 | 77.61 | 74.79 |

| Industrial power | 96.14 | 103.54 | 109.40 | 107.00 | |

| Eligible customers’ total | 172.69 | 180.99 | 187.01 | 181.78 | |

| Total electricity demand | 280.17 | 288.99 | 297.40 | 287.62 | |

Source: Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan, Graphical Flip-Chart of Nuclear and Energy Related Topics 2007.

Figure 2. Hourly Trends in Electricity Use on Peak Demand Day

Source: Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan, Graphical Flip-Chart of Nuclear and Energy Related Topics 2011.

Rules to Guide Energy-Saving Measures

What sorts of efforts could be made in households and offices? In the government’s Team Minus 6% campaign to raise public awareness about preventing global warming, the key concepts were developing risk awareness and making the issue everyone’s business. Given the circumstances of the recent disaster, however, we are far past a stage at which such ideas are meaningful. Measures that will quickly yield quantitative reductions need to be taken, with awareness raising and voluntary action plans being given no more than a supplementary role.

What is needed first of all is to gain people’s sympathy and understanding so that they will make ongoing efforts to save energy. Furthermore, members of the Diet and government must have the courage and resolve to take the lead in carrying out that which we would ordinarily consider impossible.

For this to happen, it will be important to provide sufficient explanation and information regarding the scientific (effect), economic (burden), and political (lack of disparity) aspects of the measures so that people can make their own judgments. At the same time, the political, administrative, and industrial sectors will need to demonstrate their initiative in energy-saving efforts.

Meanwhile, expecting excessive savings from large-demand customers, such as large-scale manufacturers, could negatively affect employment and the economy. If large-scale manufacturers were to halt operations, small and medium-sized enterprises in the production chain may be forced to do the same, and the resulting economic downturn may lead to shortages in the supplies needed for reconstruction and to lower tax revenues. Such a scenario must be avoided. The measures must strike a balance between energy saving and reconstruction.

Specifically, measures should be regularly checked against the following three fundamental rules to ensure that they are not misguided:

a. Sufficient information is being provided and disclosed regarding the need to save electricity and the burden on each party;

b. Politicians and civil servants are taking the lead; and

c. Regulations are being imposed on industry.

Unilateral measures implemented without sufficient explanation with reference to the above are bound to give rise to suspicions and frustrations over time: Are the measures really benefiting the affected areas? Are efforts resulting in actual reductions? Isn’t there a surplus of electricity at night? Aren’t greater reductions possible at industrial and recreational facilities? Why must we bear such a heavy burden?

Concrete Proposals

In the following section I will consider what measures are feasible, with the above fundamental rules in mind. A crucial point is whether politicians, civil servants, and industry will be able to undertake bold efforts.

Provision and Disclosure of Information

a. Status of electricity supply and consumption and forecasts of energy use in the TEPCO service area

I suggest encouraging media outlets to redistribute this information disclosed on the TEPCO website; some sources, including Yahoo Japan, are already doing this. During the peak electricity demand period from June to September (hereafter referred to as the “summer period”), in particular, actual consumption levels and total supply capacity can be shown during weather forecasts and regular news programs. If possible, it could also be displayed permanently in a corner of the television screen or distributed to mobile phones. When the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Station was shut down in 2003, electricity forecasts were provided via television, radio, Internet, and other means during the summer period from June 23 to September 5.

b. Disclosure of information on energy use by the industrial, commercial (offices, retail outlets, etc.), and household sectors in the TEPCO service area

In order that no one feels a sense of unfairness, daily energy use by the industrial, commercial, and household sectors can be disclosed, giving everyone an idea of how hard each of these sectors have tried to reduce consumption.

In particular, there are growing demands to disclose information regarding supply and demand adjustment contracts with large-demand customers, of which there are over 1,000. TEPCO may not currently have the organizational capacity to get this done. Alternatively, these customers themselves could disclose information, including their energy-saving efforts, to the extent possible. It should be noted, however, that several options exist on the menu of supply and demand adjustment contracts and that the energy-saving potential of these contracts is presumed insufficient to overcome the summer energy crisis, as will be discussed below. The options include summer holiday contracts (shifting company holidays and other measures during the adjustment period specified by TEPCO between July and September), summertime operation adjustment contracts (conducting facility maintenance, repairs, and regular inspections, designating extended vacations, and other means during the adjustment period specified by TEPCO), and peak period adjustment contracts (adjusting peak use by 30 minutes or more between 1 pm and 4 pm, as designated by TEPCO).

c. Presentation of standard energy consumption levels (business-as-usual and recommended values) for offices, retail outlets, and households

Standard energy consumption levels can be disclosed—per unit area for offices and retail outlets and both per unit area and per capita for households. This will allow people to check how much energy they are saving and could lead to further efforts, such as changing the ampere capacity of their account.

d. Provision of information

I suggest summarizing and releasing basic data for reporting on energy saving, information on organizations that could be interviewed, examples of best practices in energy-saving initiatives, and other material.

With regard to energy-saving efforts, in particular, the media, private organizations, and individuals are already engaging in various initiatives and information exchange. Fiscal allocations should therefore preferentially go to measures that generate quantitative reductions, and there should be no need for additional funding and personnel for publicity and communication efforts. Publicity should be focused on this summer’s energy-saving measures within the constraints of the current budget, such as through the public relations activities by the Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry, the Ministry of the Environment, and other existing outlets. Moreover, the government should make a point of coordinating with private-sector efforts, such as by providing web links to pages on corporate and personal initiatives; visualizing the cumulative energy saved by means of initiatives like the “light down” campaign, conducted on the summer solstice; and cooperating with lifestyle-related industry groups (such as the retail, restaurant and catering, and transport industries), organizations that have a strong impact on society (such as sports and entertainment), and the media.

Initiatives by Politicians and Civil Servants

a. Adjournment of the Diet

I suggest adjourning the Diet and relocating party headquarters outside the TEPCO service area during the summer period. Activities in Tokyo should be limited to regular meetings of the heads of the ruling and opposition parties and the maintenance of minimal party liaison functions.

b. Partial transfer of government functions

During the summer period, some government functions can be relocated outside the TEPCO service area, and the employees’ place of work and residence can be moved as well. Priority should be given to singles living alone—who can readily move—and households that have parents or relatives living in the destination area who can take in the whole family.

c. Postponement of the budget request schedule

Preparing budget requests accounts for a large part of the work that is done in the summer. I suggest reconsidering these summertime operations, such as shifting the submission deadline of regular budget requests from the end of August to October or later, with the exception of supplementary budget requests relating to post-disaster restoration and reconstruction.

d. Proactive efforts by politicians and civil servants

Employees’ working hours can be strictly managed during the summer period, encouraging them to come to work early in the morning and providing extended lunch breaks from noon to 2 pm, during which lights are turned off and office machines are not used. Air conditioning during working hours can be prohibited; this would involve revising Article 5 of the Ordinance on Health Standards in the Office, made under the Industrial Safety and Health Act, to exempt the Diet and civil service from the requirement to keep room temperatures at 28 degrees Celsius or lower. Meanwhile, the “cool biz” dress code (short sleeves and no jacket or tie) is still not permitted in the Diet (during lower house plenary sessions), but in the light of current conditions, even lighter clothing—possibly T-shirts or polo shirts and shorts—should be allowed for this summer only. Moreover, employees remaining after hours can gather in a meeting room or designated area so that power can be completely shut down in other areas of the office. Finally, employees can be required to take a paid leave of at least one week during the summer period and encouraged to travel outside the TEPCO service area with their families.

Regulation of Industries

a. Relocation of headquarters

Companies can be encouraged to set up temporary headquarters either in western Japan, including and beyond the Kansai region, or to Hokkaido during the summer period and relocate their offices and employees there. In the case of factories, which are likely to have a higher percentage of temporary workers than administrative headquarters, relocation could cause employment problems, such as layoffs of temporary workers. As a general rule, the office divisions should be relocated, while factories should adjust their hours of operation.

b. Staggering of summer holidays

I propose dividing companies (factories and offices) within the TEPCO service area into eight groups and assigning periods of one to two weeks out of the eight weeks between July and August during which they are to suspend operations, with the exception of some companies, such as those that provide financial and transportation services. During this period, only basic liaison functions should be left in operation. Employees can be encouraged to travel outside the TEPCO service area with their families.

c. Restrictions on energy use

Regarding the peak hours of energy use, time restrictions can be applied to neon signs and television broadcasting; nighttime sporting events rescheduled to daytime; events that attract large crowds (such as live concerts and fireworks displays) altered to reduce energy use, postponed to after the summer, or held outside the TEPCO service area; and hours of operation shortened at recreational facilities. Operation of factories and retail outlets can run on a rotating schedule within each business category or region.

Furthermore, supply and demand adjustment contracts can be utilized vis-à-vis large-demand customers (large-scale manufacturers). As for their energy-saving effect, expected savings at the time of the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant’s shutdown in 2003 came to about 1.4 million kilowatts through planned adjustment contracts and 1.3 million kilowatts through discretionary adjustment contracts, for a total of about 2.7 million kilowatts. But while utilizing the contracts will be imperative for coping with the aftermath of the recent disaster, suspending operations at the factories of large-scale manufacturers could also bring to a standstill the operations of small and medium-sized enterprises in the production chain. In the light of their effect on the provision of goods needed for reconstruction and on the economy and employment, we should not overly rely on supply and demand adjustment contracts.

Other Measures

In addition to the efforts proposed above, economic measures are also conceivable if they could be implemented in time for the summer period.

a. Hiking of electricity prices

TEPCO does not disclose the number of contracts or the amount of electricity sold on a per-contract-ampere basis. In exchanges with a nonprofit organization, however, TEPCO has commented that, with regard to residential accounts, 30-ampere contracts (meter-rate lighting A and B) are the most numerous but the average amperage is 40 amperes. This may mean that, for instance, half of the accounts are on 30-ampere contracts, with 40-ampere, 50-ampere, and 60-ampere contracts accounting for one-third each of the remaining accounts. Economic incentives could be used to drive the contract ampere of each account lower, with a target of 10 amperes per account. In practice, switching from 30 amperes to 20 amperes would probably be difficult. If we suppose that a one-third of 30-ampere contracts are downshifted to 20 amperes, and all 40-ampere to 60-ampere contracts are downshifted by 10 amperes each, this should reduce peak energy by 17%—at least on paper.

Professor Yukio Noguchi of the Waseda University Graduate School of Finance, Accounting, and Law proposes inducing this kind of downward shift in contract amperes by hiking the basic rate of contracts for 40 amperes and over.

The impact of measures tapping into contract amperes hinges, however, on just how the electricity is being used. Downshifting will have little effect if most households use less than the ampere capacity and have a margin of 10 amperes. Depending on actual electricity use, which is not disclosed, it may be the metered rates rather than basic rates that need revision.

As of the end of March 2011, TEPCO was not accepting changes in ampere capacity due to the disaster. It is to be hoped that this will be resumed soon, so that consumers can change the contract ampere of their own accord even if the electricity pricing cannot be revised in time for the summer.

b. Eco point system

Use of energy-saving products could be promoted by means of economic measures. An “eco-point” program for home appliances is already in place, and whether or not to continue the program will largely be a fiscal decision.

Roughly 70% of the energy used in households is consumed by air conditioners (about 25%), refrigerators (about 16%), lighting (about 16%), and televisions (about 10%). In view of their large share of home energy use, replaceability, and need for uninterrupted use, eco points could be limited to refrigerators. It should be possible, moreover, to keep down the budget by awarding points only to replacement purchases made in, or delivered to, the service areas of the Tohoku Electric Power Company and TEPCO during the three-month period from May through July.

c. “Evacuation” to conserve energy

Even if companies are to suspend operations, measures for children will be needed for families to travel outside the TEPCO service area. Supplementary plans could be introduced to promote these efforts.

I suggest that schools, from elementary school to university, close for the summer holidays from July 1 to September 15. During this period, households having relatives elsewhere can “evacuate” from the TEPCO service area for energy-saving purposes, with all members of the family in tow if possible. Local governments outside the TEPCO service area that are capable of taking in these students can organize summer camps, with special local tax grants (or subsidies) being issued on the basis of the number of students accepted. In the case of students being accepted at other organizations that fulfill certain criteria—examples of which include private entities such as nonprofits and educational institutions such as preparatory schools and language schools—grants (or scholarships) can be given out to participants in their programs.

Additionally, the government and businesses will need to formulate plans for contingencies by the end of May, such as adjusting regulations for working at home (relaxing restrictions on what documents and data can be taken home), widely distributing manuals to prepare for a higher incidence of heat stroke due to energy saving efforts, and so forth.

In Conclusion

This article has discussed measures to deal with the energy crisis expected in the summer. It is likely, however, that the problem of supply-demand gaps will not be limited to this summer. The crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station is certain to give rise to a grueling nationwide debate on nuclear power. Even if, in the medium to long term, we are to pin our hopes on replacing nuclear power with other energy sources, such as renewable energy and highly efficient thermal power generation fired with coal or gas, curbing energy demand to the greatest extent possible will be a prerequisite to making this happen.

Achieving a low-carbon society to counter climate change is an urgent issue for Japan in the first place. The short-term energy-saving measures implemented to weather the current crisis will also serve as a litmus test for medium- and long-term measures to be taken in the future. In order facilitate smooth implementation, the ruling and oppositions parties will need to reach an agreement on policies, including energy-saving measures, to be taken across party lines.