- Article

- Political Institutions

Should Civil Servants Offer Allegiance or Expertise?: Lessons from the Moritomo and Kake Scandals

May 1, 2018

The scandals threatening to engulf the Abe administration have their roots in civil service reforms that strengthened the powers of politicians. While supporting efforts to combat sectionalism, Hideaki Tanaka stresses the need for a rigorously meritocratic appointment process to ensure the independence and integrity of the bureaucracy.

* * *

The Moritomo Gakuen scandal that has been dogging Prime Minister Shinzo Abe escalated dramatically in the wake of shocking revelations of document falsification by the Ministry of Finance. To regain the nation’s trust, the government’s first priority must be a full accounting of these irregularities. Beyond that, however, we must come to grips with the underlying flaws in Japan’s civil service system.

Commentators have blamed the Moritomo and Kake Gakuen scandals on the 2014 civil service reforms that strengthened the control of the prime minister and his aides over senior-level appointments and dismissals, creating a strong incentive for officials to curry favor with the political leadership. While I agree that the 2014 reforms may have contributed to the problem, I also believe that a lack of independence is endemic to Japan’s civil service system. In the following, I analyze this fundamental flaw and suggest some necessary reforms.

Overview of Civil Service Reforms

Since the 1990s, the Japanese bureaucracy has been seen as a hotbed of corruption and a basic cause of government inertia and inefficiency. It was criticized for practices like amakudari (providing retiring bureaucrats senior positions in private industry or academia), sectionalism, and control over public policy. But institutional change was slow in coming. The first Abe administration initiated reforms with amendments to the National Public Service Act and related legislation that instituted a more meritocratic personnel evaluation system and cracked down on amakudari by prohibiting agencies from securing post-retirement jobs for their senior officials. These bills became law in June 2007.

In June 2008, under the cabinet of Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda, the Diet passed legislation (the Basic Act on Reform of National Public Officers’ Systems) that opened the way for wholesale reform of the civil service system. However, the bills needed to implement specific changes did not pass the Diet until April 2014, when the second Abe administration pushed through a comprehensive reform package. Included were the personnel reforms that are now under such intense scrutiny.

During Diet deliberations on the bills, Tomomi Inada, then minister for administrative reform summed up their purpose as follows: “These reforms are urgently needed,” she argued, “to allow for strategic deployment of personnel geared to the cabinet’s policy priorities; to address the evils of bureaucratic sectionalism so that the ministries can carry out the work of public administration seamlessly; to enable the government to formulate and pursue comprehensive human-resource strategies; and further, as I see it, to build a system in which all civil servants take pride in and responsibility for their jobs and work not for their respective agencies but for the good of the country and the people” (House of Representatives Cabinet Committee, November 22, 2013).

These are all laudable goals in principle. Now let us take a closer look at the means by which the 2014 reform sought to accomplish them.

The linchpins of the new system were (1) a centralized top-down mechanism governing the appointment and transfer of senior civil servants, (2) creation of a new unit, the Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs, to serve as the central personnel management authority for senior officers, and (3) institution of the post of hosakan —specially appointed civil servants serving as advisers to the prime minister or to a member of the cabinet. Of these, the most critical change was the new mechanism for appointing and dismissing senior bureaucrats.

Under the National Public Service Act, cabinet ministers, not bureaucrats, have long been empowered to appoint officials in their respective ministries. In practice, however, the minister merely endorsed the decisions of each ministry’s personnel department, which promoted career bureaucrats in a routine manner, without regard to merit. This supported an inbred, parochial culture within the ministries and contributed greatly to the problem of bureaucratic sectionalism. As early as 1997, the government attempted to strengthen the hand of the cabinet by requiring that each minister meet with the senior officers of the Cabinet Secretariat before signing off on appointments to the two deputy chief cabinet secretaries and the chief cabinet secretary.

The 2014 reforms legalized, strengthened, and broadened the scope of that mechanism. Under the new system, the prime minister is directly involved in the approval of appointments to all kanbushoku posts—a category that encompasses about 600 government employees, including deputy directors-general (in addition to directors-general and vice-ministers).

More specifically, the new system centralizes control over personnel appointments via the screening and selection process, beginning with “suitability screening.” Potential candidates for top positions, including those recommended by each ministry on the basis of internal evaluations, are screened by the chief and deputy cabinet secretary for their suitability from the standpoint of implementing cabinet policies. Those who pass the screening are registered on a list of candidates for senior executive positions. Each ministry uses the list to draft a plan for senior personnel appointments, which must then be approved in a meeting between the minister, the prime minister, and the chief cabinet secretary. The prime minister and chief cabinet secretary may also initiate consultations with the ministers to recommend specific individuals for hiring or dismissal.

Misuse of Political Discretion

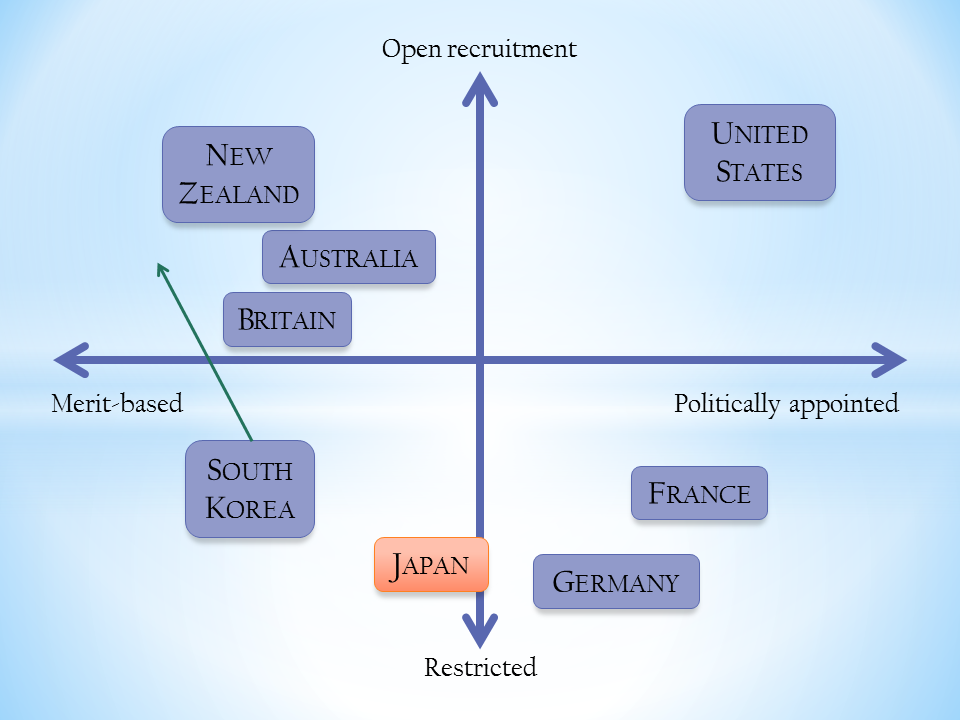

The establishment of a separate administrative structure and appointment system for senior officials, as opposed to middle-managers or rank-and-file bureaucrats, has become fairly standard practice among the world’s major democracies. Japan has taken a step in the right direction by dividing its own government personnel system into two ranks in this manner. Unfortunately, the appointment mechanisms it has chosen do not conform to the best practices adopted in countries like Britain and Australia, as I will elaborate below.

The issues surrounding the appointment of senior officials were deliberated at some length by an advisory council under the prime minister’s Headquarters to Promote Civil Service Reform, a process in which I took part. The council’s report, issued in November 2008, recommended that a list of two or three qualified and suitable candidates (evaluated on the basis of ability and performance) be drawn up for each post and that appointees be selected from that list, in keeping with international norms. We also suggested that candidates be eligible for more than one post, as appropriate. The system instituted in 2014, by contrast, gives the minister (et al.) discretion to select from a list of hundreds of candidates, leaving ample room for decisions that cannot be justified on the basis of merit alone.

Proponents of administrative reform in Japan have long stressed the need to strengthen top-down political leadership over the bureaucracy. Giving the prime minister and members of his cabinet power to appoint whomever they choose to key bureaucratic posts may seem like an obvious way to strengthen political leadership. But by allowing the prime minister and his circle to “fast-track” officials at their own discretion, the new system opens the door to favoritism in the name of “strategic deployment of personnel.” Of course, Prime Minister Abe and Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga have assured us that their policy is to choose the most appropriate person for each position, but how can we be sure that they are the most qualified? One becomes suspicious when we learn of ministry officials being removed from their posts after expressing disagreement with a political decision.

The new system does create a powerful incentive among high-ranking bureaucrats to adhere to the wishes of the prime minister and his circle, who can make or break their careers. This certainly seems to have been the driving force behind the Kake Gakuen affair, in which the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology expedited approval of a veterinary school run by a friend of Prime Minister Abe. Speaking of the scandal, former Vice-Minister Kihei Maekawa has described an “environment in which you can’t go against the wishes or preferences of the prime minister’s office and others at the center of power.”

Does this mean we should simply revert to the old appointment system? My answer is no. While there are shortcomings in the 2014 reforms, they merely exacerbated the problems already present in Japan’s civil service system. These problems, in my view, boil down to the politicization of our civil servants. By this I mean that they are unable to maintain their independence from politics—from the lobbying activities of politicians representing specific economic interests to the internal rivalries and power struggles within the bureaucracy itself. The basic cause of such politicization is a putatively merit-based appointment system with insufficient built-in mechanisms and safeguards to ensure that appointments are truly based on merit.

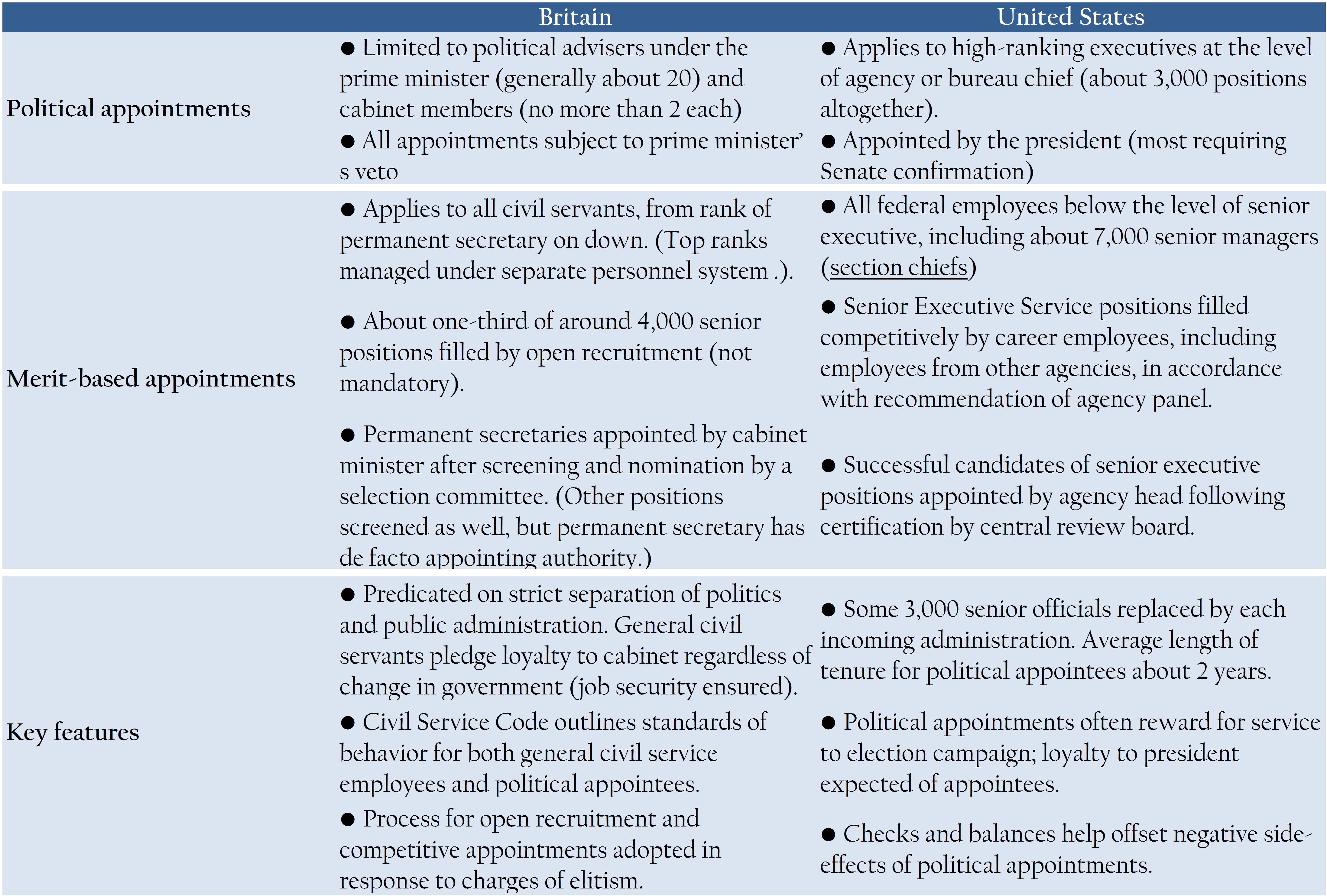

To highlight the problem, we need only compare Japan’s system with Britain’s, in which cabinet ministers have no direct authority to appoint senior officials (with the exception of their own political advisers). Candidates for executive posts are screened and nominated by a selection committee or the central personnel agency based on ability and performance standards, after which they are approved by the prime minister or relevant minister. This indirect appointment process minimizes the potential for political interference. The rationale is that if officials could be hired and fired at the discretion of the minister, they might allow the minister’s wishes and interests to override their own expertise and good sense in everything from policy making to the granting of permits and subsidies.

Political Versus Merit-based Appointments

The British system is firmly grounded in merit-based appointments. However, there are also systems that explicitly call for the political appointment of high-level civil servants.

The United States is a good example of a system that relies on political appointments to fill senior civil service posts. The president has discretion over the appointment of senior federal officials listed the Executive Schedule, including agency heads and their subordinates at the levels of deputy secretary, under secretary, and assistant secretary. This tends to foster a spoils system, in which each new president replaces the senior executives appointed by his predecessor, often with political supporters or friends. It also means that any federal official who incurs the president’s displeasure can be summarily dismissed, as we have seen time and again under the administration of Donald Trump.

Britain and Australia, by contrast, apply the principle of merit-based appointment, filling all civil service posts—from permanent secretary on down—on the basis of ability and performance. Senior positions are generally filled competitively, by open recruitment, on the basis of the candidates’ merits relative to specific job requirements and qualifications. Once appointed, these officials are expected to maintain scrupulous political neutrality. Interaction between civil servants and politicians is strictly limited. Cabinet ministers have no substantive authority over personnel decisions.

Comparison of US and British Civil Service Appointments

Classification of Senior Official Appointments among Major OECD Countries

The difference between these systems boils down to the qualities they seek to foster in senior civil servants. Political appointments foster compliance with political leadership, while a merit-based system emphasizes the value of independent expertise. In countries like the United States, senior officials are expected to serve the current administration’s political agenda. In countries like Britain and Australia, they are expected to be impartial advisers, free from political, personal, or organizational bias. Thus, the choice between the political and merit-based models hinges on one’s basic beliefs regarding the job of a civil servant.

As noted above, Japan’s system purports to be merit-based, but its poorly designed appointment mechanism has caused Japanese bureaucrats to become politicized, conducting analyses and turning out reports that advance this or that special interest instead of impartially serving the people. By consolidating authority for personnel appointments in the Prime Minister’s Office, the 2014 reforms have doubtless helped break down the walls of sectionalism, the better to advance the administration’s interests. But in the process, they have exacerbated an even more basic problem, namely, a fundamental lack of political independence.

The Reforms Japan Needs

What sort of system should Japan adopt, then? I believe there is much to learn from Australia’s experience. At one time, Australia, too, struggled with a powerful bureaucracy in which the interests of individual agencies took precedence over larger considerations and thwarted political leadership. But it was able to overcome sectionalism with the help of civil service reforms instituted in the 1980s and after.

Under Australia’s current system, senior positions equivalent to Japan’s director-general and deputy director-general are defined as senior executives, selected according to a merit-based system, with the vacancy advertised and open to all eligible persons. Screening and selection are carried out by independent selection committees. Secretaries, meanwhile, are generally selected from the ranks of senior executives, but these are fixed-term appointments. This means that one must prove one’s worth through open competition to join the ranks of a senior executive; long service under a particular department is no guarantee of promotion, as it is in Japan. Under the current system, it has also become common to tap people with interdepartmental policymaking experience, such as veterans of the Department of the Prime Minister, to top departmental posts.

Japan’s 2014 reforms did well to place senior government personnel under a central authority. This is essential to free ministry management from the grip of narrow, sectional interests. A central bureau is also needed to provide training to nurture high-level civil servants capable of providing expert policymaking support. But politicization of appointments is not the way to improve policymaking quality. What we need are independent officials who can recommend effective solutions based on objective analysis of reliable data. What specific reforms, then, should we pursue to improve the quality of public administration in Japan?

First, we need to establish a transparent and competitive appointment process. Vacancies should be advertised and open to all eligible persons whenever possible. Screening should be carried out with the participation of politically neutral bodies, such as independent selection committees and the National Personnel Authority. Then a short list of candidates for each post should be submitted to the cabinet minister and prime minister for a final decision.

Second, personnel authorities must be incentivized to acquire accurate information on all civil service officials. The Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs should be able to use that data to review the appointment proposals submitted by cabinet ministers and reject those proposals that do not match merit-based criteria.

Third, we need clear guidelines governing the scope of political appointments. The 2014 legislation instituted a system of special advisers to the prime minister and cabinet ministers. This reform was aimed at strengthening political leadership by giving the prime minister and his cabinet their own policymaking staff and lessening their dependence on bureaucrats. These advisers are politically appointed civil servants, much like the special advisers appointed directly by Britain’s prime minister and cabinet members. The important thing is to clearly distinguish between political and competitive appointments and circumscribe the scope of the former. Even in the United States, where senior positions are appointed by the president, competitive hiring is the rule, including for posts at lower levels of management.

In the final analysis, reform of the civil service means revisiting the question of what we as a nation want from our civil servants. Political appointments are fine if we want them to pursue a political agenda. But if we want them to provide expert analyses and evaluations from a position of political neutrality, then I believe we should embrace the basic model of countries like Britain and Australia.

This is not to recommend the wholesale importation of another country’s systems. One cannot abruptly impose a completely new institution and expect it to work smoothly. The failure of the National Public Service Act to establish a true meritocracy is a case in point.

Civil service reform and political reform are two sides of the same coin. Strengthening political leadership in Japan is a worthy goal, but simply expanding the power of the prime minister and the cabinet to appoint civil servants is not enough. Generally speaking, British administrations have been able to exercise strong political leadership by tapping the unbiased expertise of senior civil servants, not by controlling their appointment. In the absence of a transparent and accountable appointment system with built-in checks and balances, centralization of personnel authority can only lead to a spoils system.