- Policy Proposal

- Industry, Business, Technology

Teaming with the Social Sector to Address Society’s Challenges

December 19, 2017

The Tokyo Foundation has stressed the need for closer integration between main business operations and initiatives to address social issues since publishing its first CSR White Paper in 2014. While the pursuit of both corporate and public benefits is an important one as a long-term goal, project leader Takashi Suzuki notes that there is a need to take a closer look at the rapidly changing international and domestic realities that Japanese businesses face today.

* * *

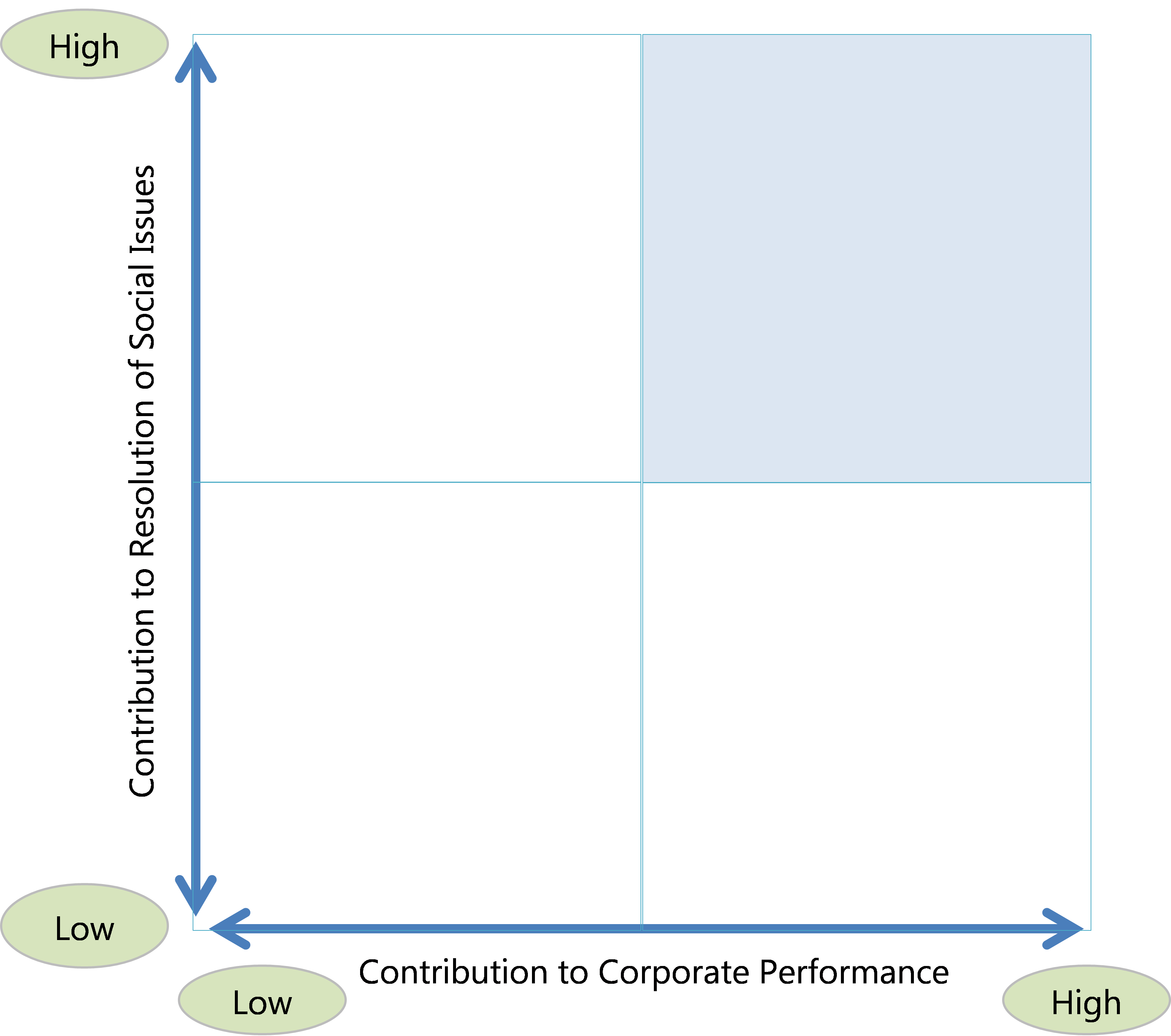

Since 2013, the Tokyo Foundation’s CSR Research Project has been collecting and analyzing information on the business sector’s role in addressing social issues, publishing the results in the form of an annual CSR White Paper. Since the first such report, published in 2014, we have stressed the need for companies to integrate action on social issues into their main business operations. By integration, we mean the pursuit of business strategies and practices that yield both corporate benefits (by contributing to business performance) and public benefits (by addressing the kinds of social issues outlined in the UN Sustainable Development Goals) (Figure 1). The results of our questionnaire surveys and interviews, as described in successive white papers, testify to the wide-ranging and often highly rewarding efforts of Japanese CSR departments, executives, and rank-and-file employees to meet the challenge of integration.

Figure 1. Integration of Corporate and Public Benefits

For all that, looking at our rapidly changing world, can we really say that we are successfully meeting the challenges of our time? To the contrary, humanity’s problems appear more daunting than ever, as social issues proliferate and grow increasingly complex and intertwined.

Meanwhile, the international and domestic environment surrounding corporate citizenship has shifted significantly since the Tokyo Foundation conducted its first CSR Survey in 2013. Taking into account the results of the fourth and latest survey, I would like to highlight certain trends in CSR against the background of those changes, focusing particularly on the challenge of dialogue and collaboration with the social sector.[1]

Big Government and Internationalism in Retreat

One of the most noteworthy changes in the international environment over the past three years is a shift in the climate surrounding international cooperation. In contrast to the global coordination that helped see the world through the 2008 subprime mortgage meltdown and the subsequent European debt crisis, the last few years have brought us the June 2016 Brexit referendum, in which the British people voted to leave the European Union, and the November 2016 election of US President Donald Trump, who ran on pledges to place “America first” in trade (by withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement) and to sharply curtail immigration.

A number of factors have contributed to this shift, but an important one is unquestionably the mounting problems that have attended the movement of immigrants and refugees, particularly in Europe. The number of refugees from such trouble spots as Syria, Afghanistan, and South Sudan has risen steeply, with the total number of refugees and asylum seekers skyrocketing over the past three years.[2] But amid domestic discontent over growing income inequality, particularly since the Great Recession, government measures to deal with the influx have been inconsistent. With national tax revenues languishing as a result of slow economic growth in the industrialized world, “borderless” policy coordination and cooperation among national governments is becoming increasingly difficult to achieve.

Growing Pressure on Business

Partly as a result, businesses have come under mounting pressure to play a bigger role in the mitigation of social problems.

In September 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, comprising 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 targets. While building on the Millennium Development Goals, the SDGs shift the emphasis from development assistance to global responsibilities shared by the developing and industrial world alike. With the role of government shrinking, international society is looking to industry to play an active role in achieving the SDGs.

In the introductory essay to our 2016 CSR White Paper, we remarked that Japan’s most advanced firms had already begun redesigning their CSR programs with the SDGs in mind. In our latest CSR survey, conducted after the publication of the 2016 white paper, we asked respondents about their companies’ interest in and actions on issues aligned with the 17 SDGs. From their response, it appears that the majority of Japanese businesses (or at least their CSR departments) are already pursuing initiatives of some sort aimed at social issues linked to the SDGs (notwithstanding concerns that alignment with the SDGs could lead to a lack of flexibility in the identification of issues). Outside of companies’ CSR departments, however, we see relatively little awareness and understanding of the SDGs, even though many companies offer such information via in-house training courses.[3]

In the 2016 CSR White Paper, we expressed our hope that the SDGs would provide a new impetus for Japanese firms to marshal their strengths and contribute to the building of a better world, enhancing their own competitiveness in the process. The Tokyo Foundation is determined to help close the gap between that ideal and reality, not merely by reporting on the current state of CSR in Japan but also by discussing concrete steps to improve the situation.

Spotlight on Dialogue and Collaboration

In the 2017 CSR White Paper, we focus on the topic of dialogue and collaboration with stakeholders, particularly in the social sector. Business is under growing pressure to help solve the sort of global challenges targeted by the SDGs and the Paris Agreement, but there is a limit to what companies can achieve alone. For this reason, we believe businesses need to pursue dialogue and collaboration with a wide range of internal and external stakeholders.

As we have noted over the years, social-sector groups, which focus on social issues on a daily basis, have a particularly important role to play in helping businesses identify issues to address. Yet our surveys have shown that, while most businesses conduct some form of stakeholder dialogue, they are much less likely to engage with the social sector than with other stakeholder groups (shareholders and investors, customers and consumers, employees, the community, and business partners) (see Figure 2). Our latest survey results show no appreciable change in this regard. Moreover, the percentage of companies involved in collaborative initiatives with the social sector actually seems to be on the decline, a trend confirmed by other surveys.[4]

Figure 2. Strengths and Weaknesses of Japanese CSR

In the following, I would like to expand briefly on the vital resources that social-sector groups have to offer and suggest directions for cultivating productive dialogue and collaboration.

Strengths of the Social Sector

Among the many strengths of the social sector, those listed below are most pertinent in terms of what businesses stand to gain from partnering with nonprofits and similar groups. (Note that the social sector encompasses organizations of varying sizes and backgrounds engaged in a wide range of activities, and that not all the attributes below apply to every group.)

・ Expertise: Because of their keen interest in specific social issues, social-sector groups often have a rich fund of knowledge and experience in analyzing and addressing those issues, as well as a network of professional connections to summon in instances where their own expertise is insufficient.

・ Responsiveness: With their concerns and resources concentrated on social issues, social-sector groups tend to be alert to the emergence of new problems (sometimes even anticipating them) and capable of responding quickly and flexibly.

・ Independence, objectivity: Because social-sector groups usually have no direct economic ties with any of the company’s internal stakeholders, they are able to maintain an independent, objective perspective when dealing with them.

・ Ties with the regional community: Social-sector groups that deal with local issues maintain a different quality of relationship with local government agencies, companies, and citizens than do profit-making companies, which interact primarily through the provision of goods and services (except in cases where they play a prominent role as local employers or taxpayers).

Not being primarily oriented to profit-making activity, social-sector organizations may lack extensive financial or organizational resources. These, though, are precisely the areas in which corporations excel. By complementing one another’s strengths and weaknesses, the business and social sectors have the potential to form highly productive partnerships that benefit both sides substantially.

Flagging Momentum

The top reasons companies give for not collaborating more with the social sector are “We have no point of contact with NGOs or NPOs” and “We don’t know which NGOs and NPOs are appropriate as partners.” [5] A comprehensive analysis of the relationship between Japanese businesses and the social sector at home and abroad is beyond the scope of our survey, but our interviews with personnel in both sectors confirm the impression that progress in collaboration has been disappointing and point to the following circumstances as possible explanations.

First, there has been a loss of momentum since the surge of activity following the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami of March 2011. The disaster was a CSR wake-up call for Japanese businesses, driving home the idea that corporations must be a responsible member of the community, since a sustainable society is necessary for a sustainable business. Through their involvement in various post-disaster relief and reconstruction projects, companies acquired a deeper understanding of social issues and gained experience partnering with the social sector. However, six years later, with such projects winding down, many businesses are having trouble charting the way forward.

At the same time, other companies have worked to develop corporate initiatives by which they can make their own unique contribution to society, without the help of social-sector groups, especially internal policies and programs aimed at promoting social inclusion and independence among society’s vulnerable.

Another way to explain the lack of progress is that relatively few companies choose to address the same type of issues targeted by social-sector organizations. This may be particularly true in Japan, where the majority of NPOs and NGOs tend to focus on local problems. This fragmentation of social action can make it difficult for corporations to find promising avenues for collaboration.

Tips for Productive Collaboration

Of course, each case is different and presents its own challenges. Those with experience planning, executing, and evaluating successful collaborationsーcorporate officers, social-sector professionals, and CSR evaluatorsーoffer the following advice for marshaling the complementary strengths of the business and social sectors.

Corporate officers say that a company interested in partnering with the social sector should find some shared concern that it wishes to address through a CSR initiative. They also advise that the company articulate, from the earliest stages of dialogue, what it hopes to gain from such activity. The company should treat the partner organization as an equal at all stages and work closely with it to clarify what each side brings to the partnership and to design a collaborative program that assigns an appropriate and meaningful role to both.

The advice from social-sector professionals is that groups should keep in mind that the social sector has a relatively short history and low profile in Japan. Having established a track record within its field of endeavor, an organization needs to interact actively and honestly with its prospective corporate partner, identifying common objectives, defining roles, and deepen mutual understanding. Intermediary support organizations can play a constructive role by facilitating such communication and expanding the scale of social initiatives.[6]

Finally, CSR evaluators tell us that Japanese companies need to become more attentive to their deep-seated, often unconscious assumption that it is job of the state to address social ills and enhance the public good. They also urge companies to do more to support and promote volunteerism and community action among their employees.

It Starts with Dialogue

Perhaps the fundamental message of the foregoing is the need to reaffirm the essential role of dialogue. By establishing communication with people who view things from a different perspectiveーparticularly those whose primary goal in tackling social issues is not the pursuit of profitsーa company can provide employees in every division with opportunities for growth. Even if one cannot, ultimately, take part in concrete action on a given issue, participation in “outside-in” dialogue on ways to address that problem reaffirms one’s ability to make a difference to society, whether individually or as a business.

As things stand, far too few Japanese companies can claim that their own CSR programs and objectives are widely understood and embraced by executives and employees outside the CSR department.[7] In the 2015 CSR White Paper, we discussed this challenge in terms of the “internalization” phase of the CSR process.[8]

With humanity’s challenges proliferating and growing increasingly complex, each company must act now to build an internal consensus on which issues to tackle, how best to contribute, and how to develop into a stronger and better corporation while addressing social problems. It is time to enter into an internal discussion on these issues, making maximum use of the perspective gained from meaningful dialogue with the social sector.

We at the Tokyo Foundation have called for the integration of social action into business operations as a long-term CSR goal. In the months ahead, we intend to reassess whether such a goal is an appropriate one for businesses offering a wide range of goods and services or global corporations with stakeholders in far-flung regions of the world. We will examine what sort of criteria would be appropriate for evaluating external and internal policy and conduct, given the realities of Japanese business today.

[1] Beginning with this year’s report, we have adopted the term “social sector” to refer collectively to nonprofit, nongovernmental, and other civil-society entities.

[2] UNHCR, “Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2016,” www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5943e8a34/global-trendsforced-displacement-2016.html .

[3] Our own findings are confirmed by the results of other surveys. For example, in a survey of Japanese companies conducted by the Business Policy Forum, Japan, in November-December 2016, a “lack of understanding within the company” was chosen by the largest number of respondents (57.7%) as a “problem hindering SDG initiatives.” In a September 2016 survey of companies and organizations in the Global Compact Network Japan, jointly conducted by GCNP and the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, only 28% of responding companies affirmed that top management had embraced the SDGs, and just 5% reported the same for middle management.

[4] For example, the Toyo Keizai CSR Survey has recorded a decline in the number of respondents reporting “cooperation with NPOs and NGOs.”

[5] See Zentaro Kamei, “How Japanese Businesses Practice Social Sustainability: A Profile,” Tokyo Foundation CSR White Paper 2015, https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=391 .

[6] Intermediary support organizations are organizations that help channel support to NGOs and NPOs by linking them with citizens, businesses, government agencies, and one another. In Japan, the ISOs Japan NPO Center and NPO Support Center have helped to organize such programs as the Save Japan Project, jointly sponsored by 60 environmental groups nationwide.

[7] In addition to our own findings, in a CSR survey of Keidanren member companies conducted by the Council for Better Corporate Citizenship, the challenge most frequently identified by respondents as necessary to further progress in CSR was “employee understanding and behavior vis-à-vis CSR.”

[8] See Zentaro Kamei, “Building Responsive Companies: The Tokyo Foundation’s CSR White Paper 2015,” Tokyo Foundation CSR White Paper 2015, https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=469 .