- Article

- Fiscal Policy & Social Security

Japanese Healthcare at a Crossroads (2): Rethinking Reimbursement for Integrated, Cost-Effective Care

November 28, 2017

Japan’s fee-for-service healthcare reimbursement system, while limiting the cost of individual services, provides almost no incentive for efficient, integrated care. Kiyoyuki Tomita looks at recent trends in payment reform and imperatives for the future.

* * *

In the highly interdisciplinary field of healthcare policymaking, economics plays an important role. One of the key economic challenges facing policymakers today is that of designing incentives to encourage smart decisions by providers, patients, and other players in the healthcare system. The main tool for this purpose is the reimbursement system for medical and nursing-care services.

Although Japan’s uniform fee schedule, updated biannually, limits what providers can charge per service, overall healthcare costs have continued to soar under the nation’s fee-for-service payment model, threatening the sustainability of the social security system as a whole. For this reason, policymakers are now turning to other cost-containment measures aimed at insurers, local government agencies, and individuals, offering incentives for preventive care and healthy behavior, as through regular checkups and better health information. In the following, I examine emerging trends in the effort to build cost-effectiveness into the healthcare system.

Sharing the Burden?

Japan’s system of universal health insurance is actually a patchwork of numerous insurance schemes. At last count, there were approximately 3,400 insurers in Japan altogether. That said, the plan in which one enrolls is determined not by preference but by such factors as profession, place of residence, and age. In the absence of true consumer choice, there is no real competition among insurers. Instead, the government has pursued reforms aimed at strengthening the function of insurers and containing healthcare expenses via incentives for more efficient care.

Containing costs means creating an environment in which not just government but all players in the system share the responsibility. Because social security is predicated on social solidarity, it is important for each player to be aware of their responsibility within the system. But that requires access to clear, comprehensible information regarding burdens and benefits.

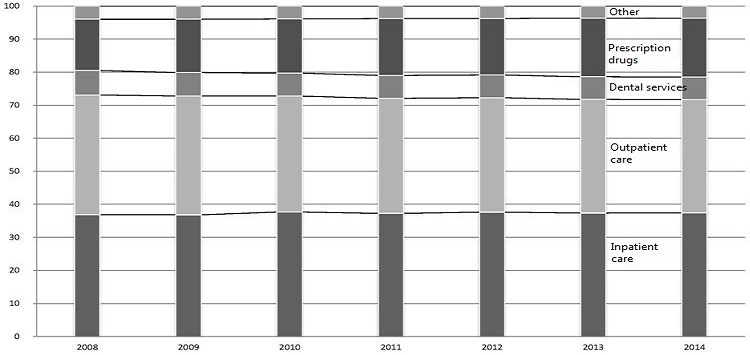

Breakdown of Healthcare Costs

Unfortunately, the financing of Japan’s healthcare system is extremely complex. The application of tax revenues and transfers between national government, local government, and various insurers make it very difficult to see how burdens relate to benefits. The system insulates most individual participants from an awareness of the true costs of the services they give or receive. To be sure, the high price of many of the new drugs appearing on the market has made people more cognizant of rising healthcare costs and the problem of sustainability. Even so, it is exceedingly difficult for them to grasp how they fit into the big picture.

In addition, the problem of information asymmetry raises special challenges to cost containment in the area of healthcare. Although the digital revolution has made it much easier for laypeople to access medical information, the knowledge gap is still difficult to bridge, given the advanced level of education, expertise, and experience required of healthcare professionals. Insurers may be able to gather and analyze the massive amount of information needed to narrow that gap, but they have almost no direct impact on individual healthcare decisions. Nor are patients empowered to make the kinds of judgments consumers of other goods and services routinely make.

Under these conditions, incentives aimed at insurers, local governments, and patients are probably insufficient to control costs; healthcare professionals themselves must be motivated to contain costs as well. As a practical matter, healthcare decisions begin with a patient’s examination by a physician. It follows, then, that the system should provide the physician and patient with incentives to contain costs.

Until now, the government has relied on top-down, macro-level mechanisms, such as the fee schedule and centralized planning, to control costs. As a result, there was relatively little need for providers to concern themselves with cost issues at the micro level. Of course, from the standpoint of business management, hospitals and clinics have a major stake in the fees they are paid, and the medical establishment is frequently at odds with the government when it comes to deliberating cost-control measures. But apart from the shift toward generic drugs, one sees little evidence of cost-consciousness at the doctor-patient level.

Encouraging Creative Solutions

Any discussion of cost-containment measures in healthcare inevitably raises concerns about the possible impact on quality of care. However, quality is the central and abiding concern of healthcare professionals. In Japan, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and nursing-care providers have established independent professional organizations with the aim of upholding the ethical standards of their respective fields. This is why healthcare providers themselves are in the best position to contain costs without compromising quality of care. To maintain the sustainability of our healthcare system, we need a payment system that links cost-consciousness to the natural impulse of healthcare professionals to improve the quality of care.

As we have seen, Japan’s basic payment system is fee-for-service, with each fee determined by a uniform nationwide schedule. (Long-Term Care Insurance sets benefit limits according to care level for some services.) In revising the fee schedule, the government raises and lowers the approved fee for each service with the aim of discouraging or encouraging the use of that service in accordance with its policy goals. In other words, uniform standards set by national government authorities intervene directly in the relationship between the doctor and patient or the care provider and user.

But recent trends suggest a gradual movement away from this model. For example, the adoption of the DPC (diagnosis procedure combination) system for certain categories of hospital-based acute inpatient care, in combination with the use of critical paths, has promoted greater standardization and efficiency of care. By bundling payment for inpatient treatment and giving healthcare institutions leeway to come up with the most cost-effective solution, this system takes a small but important step toward better and more efficient healthcare.

The other major reform aimed at cost-effective care is the Integrated Community Care initiative, which calls for the development of seamless networks of community-based medical and long-term care services. The latest revisions of the healthcare fee schedule incorporate a number of incentives for integrated care and the primary-care providers that coordinate it [1] , including special reimbursements for “integrated community care ward inpatient hospital charges,” “integrated community care treatment charges,” “community care treatment surcharges“ (as of 2014), and “preferred pediatric treatment charges” (as of 2016), as well as integrated evaluation of dementia care, preferred dental providers, and preferred pharmacists.

The new fees signal a gradual shift from the traditional fee-for-service system to bundled payments consistent with the aims of integrated care. However, as yet bundled payment is limited to pediatrics, management of certain chronic diseases, and some drug dispensing. In most communities, the seamless communication and coordination envisioned between clinics and hospitals, clinics and specialists, and medical and nursing-care facilities is still a long way off.

Fee-for-service reimbursement and bundled payment each have their merits and drawbacks. In principle, fee-for-service reimbursement gives providers maximum freedom to determine a course of treatment while minimizing the financial risks. Yet a detailed, carefully calibrated fee schedule like Japan’s tends to limit providers’ choices. Bundled payment, by contrast, encourages providers to come up with their own solutions for efficient delivery and optimum integration of care, but it also places greater financial risk on providers. In addition, quality assurance mechanisms are needed to ensure that bundled payment does not lead to withholding of care.

Since neither system is perfect, the best answer is doubtless to design some combination of the two, keeping in mind current circumstances and imperatives, as well as the legacy of the past. For Japan, the central challenge today is to design a payment system that supports integrated community-based care.

Communities as Agents of Reform

Primary care has emerged as a major focus of healthcare reform initiatives worldwide, and Japan’s Integrated Community Care initiative is no exception. It is essential to strengthen primary care to ensure the delivery of continuous patient-centered integrated care. To this end, countries around the world have implemented a variety of reforms, including advanced information systems and payment reforms, tailored to their own circumstances. Few areas of reform are more influential than the method of reimbursing healthcare providers.

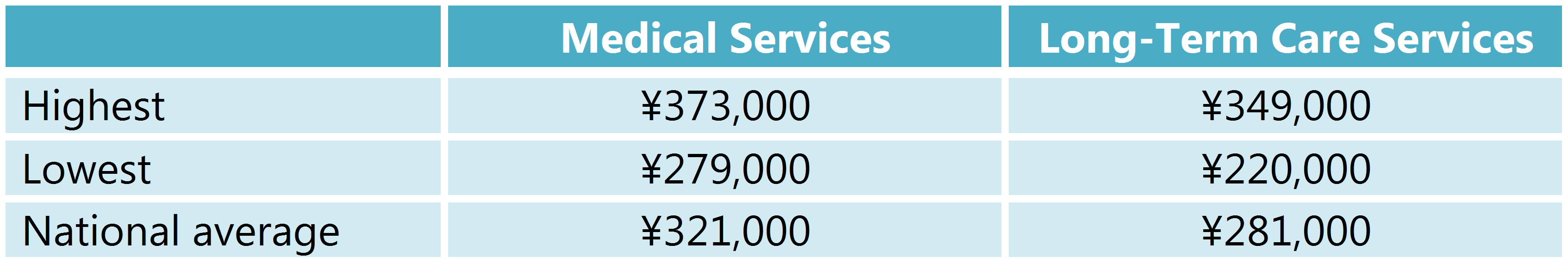

The defining challenge for Japanese healthcare policy going forward is that of containing costs while enhancing quality. The optimal solution will vary for each community, depending on local resources, circumstances, and history, as well as factors like housing, transportation, and level of civic involvement. Accordingly, responsibility for healthcare policymaking is gradually shifting from the national government to the prefectural and municipal levels, as seen in the Integrated Community Care System. Nonetheless, with a few exceptions, healthcare fees and reimbursement methods remain under the rigid centralized control of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Prefectural Disparities in Per Capita Healthcare Costs

We are rapidly approaching the limits of what centralized policymaking and regulation can accomplish. To ensure the sustainability of our healthcare system, we need to decentralize and develop a system that encourages independent and creative problem solving by local providers and agencies. Healthcare is not a one-way, top-down process. It is a partnership, predicated on mutual trust, in which providers, patients, users, and family work together to fight illness and enhance the quality of life. The power to transform our healthcare system lies with our local communities.