Marks & Spencer is a major British retailer with some 850 stores in the United Kingdom—including department stores, supermarkets, and convenience stores—and branches in 59 countries around the world. It is also a world-renowned presence in the field of CSR. Under a CSR strategy called Plan A, M&S has vigorously engaged nongovernmental organizations and other stakeholders in dialogue and translated such dialogue into collaboration, partnering with them to involve customers in Plan A and enlisting them in a larger effort to address environmental and social problems. In 2014 alone, the company received 36 awards for its CSR initiatives.

Getting Customers Involved

A brief tour of the M&S Plan A website page conveys a sense of the company’s commitment to getting customers involved. Under the words “Welcome to Plan A” are three main menus, with “Get Involved” in the center. Under “Get Involved” are the words “Be Inspired by M&S Plan A.”

Clicking “Get Involved” takes you to an overview of eight CSR projects currently underway. The introductory text on the page contains these memorable words: “Environmental and ethical goals aren’t achieved just by talking—we believe in doing. Over the years we’re proud to have got involved in a number of great projects that really do make a difference. Why not join us? . . . Let’s do it!” The orientation is participatory instead of explanatory, opening a door to engagement rather than pointing out the company’s own accomplishments. It involves the viewer and reveals the company’s determination to make a difference by joining forces with others.

Let us look at some of these customer-involvement projects. In one, you can donate a portion of the price of coffee to a charity that supports cancer victims. In another, you can join with M&S employees and a marine conservation society to clean up the country’s beaches. You can contribute money or supplies to an organization that helps the homeless and promotes housing for low-income families, or you can recycle used clothes by donating them to an international aid organization.

All are projects that M&S is carrying out in partnership with various NGOs. In other words, each of these opportunities for customer involvement is the result of collaboration between M&S and a nonprofit organization.

These partnerships are products of the company’s ongoing dialogue with various NGOs. In fact, engagement with NGOs and other stakeholders is central to Plan A. Thanks to the company’s assiduous and continuing efforts, engagement and collaboration with stakeholders have become an everyday affair at M&S.

Beginnings of Plan A

Why does M&S place such emphasis on stakeholder dialogue? What does it hope to get out of it?

The answer to that question can be found in the content of Plan A. Plan A is not just a gimmick cooked up by the company’s CSR department. It is a paradigm change involving the company’s core philosophy and the way it does business. So, what exactly is Plan A? Let us take a look at the plan’s origins and development to understand why Marks & Spencer, which has shaped its business model and brand image around Plan A, has embraced stakeholder engagement so enthusiastically.

Marks & Spencer began as a family-run business in the late nineteenth century. Even after the family fully relinquished control in the 1980s, a strong current of paternalism persisted in the company’s management style. Paternalistic management tends to be inward looking, looking after employees as if they were family but paying relatively little attention to the concerns of external stakeholders. The idea of incorporating external feedback is foreign to management in such a corporate culture. While M&S spent considerable sums on charitable causes in those days, such philanthropy was completely divorced from the company’s business operations.

This culture began to change as the concept of CSR took hold. By 2006, the company’s CSR efforts in the areas of compliance and risk management, as well as philanthropy, had earned it the title of Company of the Year from Business in the Community, Britain’s corporate network for social responsibility. But M&S recognized that further change was required.

The main impetus for the company’s transformation into a business that grasped the importance of stakeholder engagement and made it central to corporate management was the appointment of Stuart Rose as chief executive officer in 2004. When Rose took the helm, M&S was still in the habit of handing environmental and social concerns over to a dedicated CSR team to deal with them separately from other management issues. Because of this, Rose felt that the company’s lofty social, environmental, and ethical goals all too often failed to materialize as concrete action. He felt that what the company needed to do was reassess its day-to-day operations, or “the way we do business,” in the light of its social, environmental, and ethical responsibilities, and to take the lead in addressing important issues.

In 2007, under Rose’s vigorous leadership, M&S released Plan A, a five-year plan outlining 100 commitments relating to five priority environmental, social, and ethical issues: Climate Change, Waste, Sustainable Raw Materials, Fair Partner, and Health. As the company’s 2007 “How We Do Business” report explained it, “We’ve only got one world. And time is running out.” The thinking was, “There is no plan B.” To tackle the problems facing society, it was necessary to commit to Plan A, which meant changing the way the company did business.

Governance Structure

Chief Executive Stuart Rose announced up front, “The changes we are planning will only succeed if Plan A is fully integrated into the way we do business.” In other words, he made implementation of Plan A a basic governance issue. With his emphasis on top-down initiatives, Rose replaced the Corporate Social Responsibility Committee with a new executive-level committee. The How We Do Business Committee, as it was dubbed, met monthly with himself as chair and consisted of the company’s senior officers for social, environmental, and ethical affairs.

Each of Plan A’s five themes was assigned to a committee member, who assumed responsibility for ensuring that the commitments in that area were met. One member was also put in charge of employee involvement, demonstrating the company’s seriousness about spreading the word to employees. With the structures for implementation in place, Marks & Spencer began putting Plan A into action.

One of the most noteworthy features of Plan A is the explicit understanding that dialogue and collaboration with external stakeholders are essential to its implementation. In the 2007 sustainability report, M&S concluded its introduction to the Plan A philosophy as follows: “We don’t have all the answers, and we will need to work with suppliers, the Government and other partners to put Plan A into action.”

Listening to Stakeholders

Let us look at Plan A more closely to see how this works. Under each of the five themes mentioned above, the plan provides a list of relevant external stakeholders, including specific NGOs involved in that area. For example, under Sustainable Raw Materials, it lists not only customers, suppliers, and shareholders but also a wide-ranging selection of NGOs: the Marine Stewardship Council, the Marine Conservation Society, the WWF-UK, the Forest Stewardship Council, the Forest & Trade Network, LEAF (Linking Environment and Farming), and the RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals).

The External Stakeholders of Priority Environmental, Social, and Ethical Issues

It also sets forth 20 commitments in that area, such as, “phasing out a further 19 pesticides used in fruit, vegetable and salad production by the start of 2010 in addition to the 60 we have already banned,” “ensuring all the fish (fresh and processed) we sell is Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certified or, where MSC is not available, another equivalent independent standard,” and “work[ing] with animal welfare groups to develop sourcing policies on animal welfare for leather and wool.” The plan does likewise for the other four themes, naming a total of 21 partner NGOs in the process.

Specifying organizations by name in connection with each of the plan’s major initiatives demonstrated the company’s commitment to meaningful dialogue and collaboration. Once it had put those names in writing, there would be no backing down. With other parties involved, it could hardly lie about what it had done or not done. And to say, “We meant to do it, but it didn’t go as planned,” would compromise the company’s credibility as a trustworthy brand.

Engaging with external stakeholders almost always causes headaches. It takes time to build mutual understanding, and sometimes the two sides cannot see eye to eye. As a result, such engagement is all too often reduced to a formality, with management holding a meeting or two in the name of dialogue. But M&S had made a written pledge to achieve specific goals by listening and collaborating with specific stakeholders. One cannot make such a commitment in writing unless one is prepared to follow through.

The How We Do Business Committee was charged with upholding that commitment. In each division and department, management actively engaged in dialogue with its stakeholders. On any given day, it was almost certain that someone somewhere in the company would be listening to and interacting with stakeholders. Through its dialogue with NGOs, management received valuable feedback regarding the current version of Plan A, including some harsh criticism of individual commitments, and gained new perspectives on social and environmental issues that drove the identification of new commitments.

Such exchange also gave M&S an opportunity to explain the kinds of things it could and could not do as a private corporation. The aim was not asserting one side’s dominance or superiority over the other; it was building relationship in which both sides could talk openly, on an equal footing. This is the kind of relationship that leads to collaboration.

Making Plan A “How We Do Business”

The original Plan A was a five-year project intended to fulfill 100 commitments by 2012. Prior to the target date, the company unveiled Plan A 2010, adding 80 further commitments. The explicit goal this time was to make Plan A part of the company’s DNA, building the spirit of Plan A into all 2.7 billion of its products. The new plan preserved the five original environmental, social, and ethical themes more or less intact: Climate Change, Waste, Natural Resources, Fair Partner, and Health and Wellbeing. But Plan A 2010 also featured two new pillars aimed at extending the plan’s reach and integrating it more fully into business operations. These were Involving Customers and Making Plan A ‘How We Do Business.’

To achieve its goals, the company moved to strengthen its Plan A management and promotion apparatus. In place of the How We Do Business Committee, it created a two-tiered apparatus. The How We Do Business Executive Committee, made up of all the members of the board and chaired by the CEO, would meet every two months to ensure that the company’s business strategy meshed with Plan A. The How We Do Business Operating Committee, made up of division heads and chaired by the director of Plan A, would meet every month to review day-to-day operations and performance. This two-tiered framework has continued up to the present.

Plan A 2010 also established key performance indicators for all 180 commitments and a mechanism for monitoring progress toward the objectives. In addition, it established Plan A targets for all its executives and adopted a system linking bonuses to the achievement of those objectives.

Like the original Plan A, the new plan spelled out the pivotal role of dialogue and partnership with stakeholders. With the development of a stronger Plan A management system, stakeholder engagement became even more central to the company’s management practices.

Further Evolution of Plan A

In 2014 M&S adopted Plan A 2020, and set about building a whole new mechanism for achieving sustainability. The change is apparent in the plan’s pillars. Previously, the pillars of Plan A were specific social and environmental issues, such as climate change and waste. In truth, neither the process of identifying objectives nor the internal systems for achieving them were particularly novel compared to the perspective adopted by Japanese businesses. However, all that changed dramatically with Plan A 2020. The new pillars of the company’s long-term drive to become “a truly sustainable retailer” are more in the nature of corporate ideals: Inspiration, In Touch, Integrity, and Innovation.

Quite frankly, these headings are so abstract that it is difficult to know what their intent is without delving further. Let us see if the captions provided in the 2014 report shed some light on the matter. Under Inspiration, we read, “We aim to excite and inspire our customers at every turn”; under In Touch, “We listen actively and act thoughtfully”; under Integrity, “We always strive to do the right thing”; and under Innovation, “We are restless in our aim to improve things for the better.”

From these brief glosses, we can see that the four new pillars are in fact standards of conduct. The social and environmental themes that previously served as Plan A’s pillars are embedded in these standards, and any further social and environmental challenges that the company takes on henceforth will likewise be embedded in them. By holding up these four standards, the company is encouraging individual employees to think how each one applies to their work. This fosters initiative and autonomy, fostering the internalization of the spirit of Plan A in each of its employees.

Dialogue and Collaboration with Stakeholder under Plan A

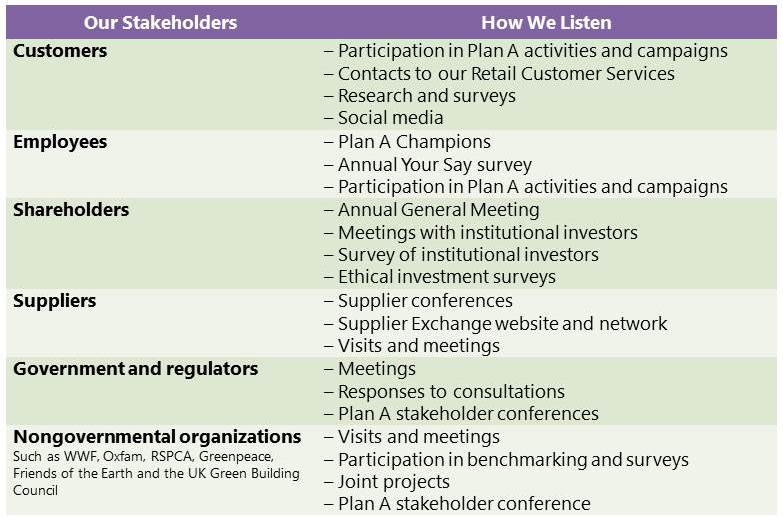

In terms of stakeholder engagement, the latest report specifies the ways in which management listens to and works with each of the six categories of stakeholders: customers, employees, shareholders, suppliers, government and regulators, and nongovernmental organizations. Like previous plans, the latest version provides the names of specific NGOs, citing WWF, Oxfam, RSPCA, and Greenpeace among their major partners. Engagement with such organizations takes the form of visits and meetings, participation in benchmarking and surveys, joint projects, and Plan A stakeholder conferences. The 2014 report notes that NGO stakeholders have voiced concern about supply chain management, transparency, the living wage, food waste, reporting, and the impact of climate change.

In addition, the M&S website specifies 11 NGOs that are actively engaged in partnerships with the company.

When M&S first launched Plan A, it announced its commitment with the words, “Because we’ve only got one world. And time is running out.” In his introduction to Plan A 2020, Mike Barry, director of Plan A writes, “If there is one overarching lesson we draw from the first seven years of Plan A, it’s one of humility. We won’t change the world alone; in fact we can’t even change our own business alone . . . we know that the importance of partnership is growing.” This is exactly why M&S has put so much effort into honest dialogue with its stakeholders. Today, the partnerships that have grown out of such dialogue have become standard operating procedure for Marks & Spencer.

The Tokyo Foundation survey of Japanese businesses reveals that those companies that engage in dialogue with NGOs, NPOs, and socially vulnerable groups are more conscious of social and environment problems and are more likely to be taking concrete steps to address those problems. The example of Marks & Spencer confirms the idea that serious dialogue leads to constructive action. By engaging NGOs in dialogue as equals, management has gained a new awareness of social and environmental issues that preoccupy those organizations. This has led to new Plan A commitments and opened the way for partnership with the NGOs. Dialogue and partnership are the keys to Marks & Spencer’s success in building and maintaining a reputation as a global leader in CSR.

To be sure, as a British firm, Marks & Spencer is operating in a particularly favorable climate for initiatives of this sort. Britain’s pursuit of smaller government in the cause of fiscal austerity has greatly augmented the role of its civic groups, local communities, and NGOs, which have acquired considerable financial and political clout as a result. These circumstances have fostered greater mobility of human resources between sectors. Those NGOs with the highest name recognition have drawn talent from the private sector, and business has recruited personnel from the nongovernmental sector as well. As a result, an increasing number of people in both sectors are able to communicate in the same language, and people with experience in both sectors are establishing human links between businesses and NGOs. For this reason, Britain today provides a particularly fertile ground for dialogue between the two.

This may convey the impression that the situation in Japan, by contrast, is unconducive to the kind of dialogue that can progress to collaboration. It is true that until now few Japanese companies have made dialogue with specific NGOs part of their CSR plans or engaged with such organizations on equal terms the way Marks & Spencer has. But is Japan’s situation really so different from Britain’s? Is there not good reason to suppose that the environment in Japan will come increasingly to resemble Britain’s as the role of the central government declines and other stakeholders are called on to play a larger role in addressing social problems?

In Japan as in Britain, a growing number of young people care deeply about these issues. Some have even made the switch from the business to nonprofit sector. Japanese companies have begun seconding personnel to work with nonprofits on a pro bono basis, and nonprofits have dispatched personnel to work with businesses. Slowly but surely, these trends are laying the groundwork for meaningful dialogue and partnership.

How quickly we can build this groundwork into a sturdy foundation for success will be a challenge for Japanese society as a whole in the years ahead. Marks & Spencer’s experience engaging and partnering with NGOs for the betterment of society holds rich implications for Japanese business in the years ahead.