- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Making CSR Synonymous with Corporate Management: Fuji Xerox

July 14, 2016

Fuji Xerox espouses the principle that corporate social responsibility is synonymous with corporate management. The Top Commitment section of the company’s Sustainability Report 2014 contains a clear exposition of the meaning of CSR and of the efforts being made to integrate business operations and CSR initiatives to address social issues. [1] The document explains what CSR is in concrete terms in the context of the company’s raison d’être in society. [2]

Efforts toward Quantification

Talk is cheap, some may note. But at Fuji Xerox, words are backed up with action. The sustained implementation of honest effort has resulted in the evolution and deepening of the company’s CSR program.

Many companies report that they have a hard time getting their business divisions to embrace CSR goals, especially when the task entails setting and managing quantitative targets and monitoring progress. This points to the difficulty of achieving the integration of CSR activities with business operations—the central theme of the Tokyo Foundation’s 2014 CSR White Paper. Our 2015 report, meanwhile, reveals that even when companies are monitoring the results of their CSR activities and the progress toward achieving quantitative targets, there is an overall tendency for individual activities to become drawn out. This can be taken as an indication that the PDCA—plan, do, check, act—cycle is not being properly carried out and that the quantitative targets were just for show.

Progress, indeed, is being achieved in some quarters toward the quantification of CSR. In the area of environmental issues, for example, where quantification is easy, numerical goals have been adopted in an effort to prevent pollution and mitigate climate change. The impact of such measures can be calculated by keeping track of the reductions in energy consumption. Quantification is also widely conducted to confirm the achievements of a company’s own CSR activities.

But companies still maintain that evaluating results quantitatively is difficult. In the case of environmental issues, relevant laws and regulations (including voluntary “soft laws” introduced by industry groups) set clear standards, making it easy to measure performance. But the regulatory frameworks for such issues as human rights, poverty, and gender normally have only qualitative provisions and are vague in defining to whom they apply; as such, it can be difficult to identify achievements that all can agree as having been successful. The difficulty many companies cite in quantifying the results of initiatives other than those relating to the environment may, in truth, be an admission that they do have the means to quantify the results of such initiatives.

In his Top Commitment message, President Tadahito Yamamoto declares: “Goals established by management are embedded in frontline plans for product development, procurement, manufacturing, sales, and other activities. As I have been emphasizing, it is critically important to clarify the link between CSR and the mission and objectives of each organization and to achieve a full integration between CSR and our core business.” This is something that many companies are finding difficult to achieve. The following is an overview of Fuji Xerox’s CSR initiatives, with a focus on the quantification of targets and results.

CSR as a Key Component of Business

Let us look more closely at the contents of Fuji Xerox’s Top Commitment.

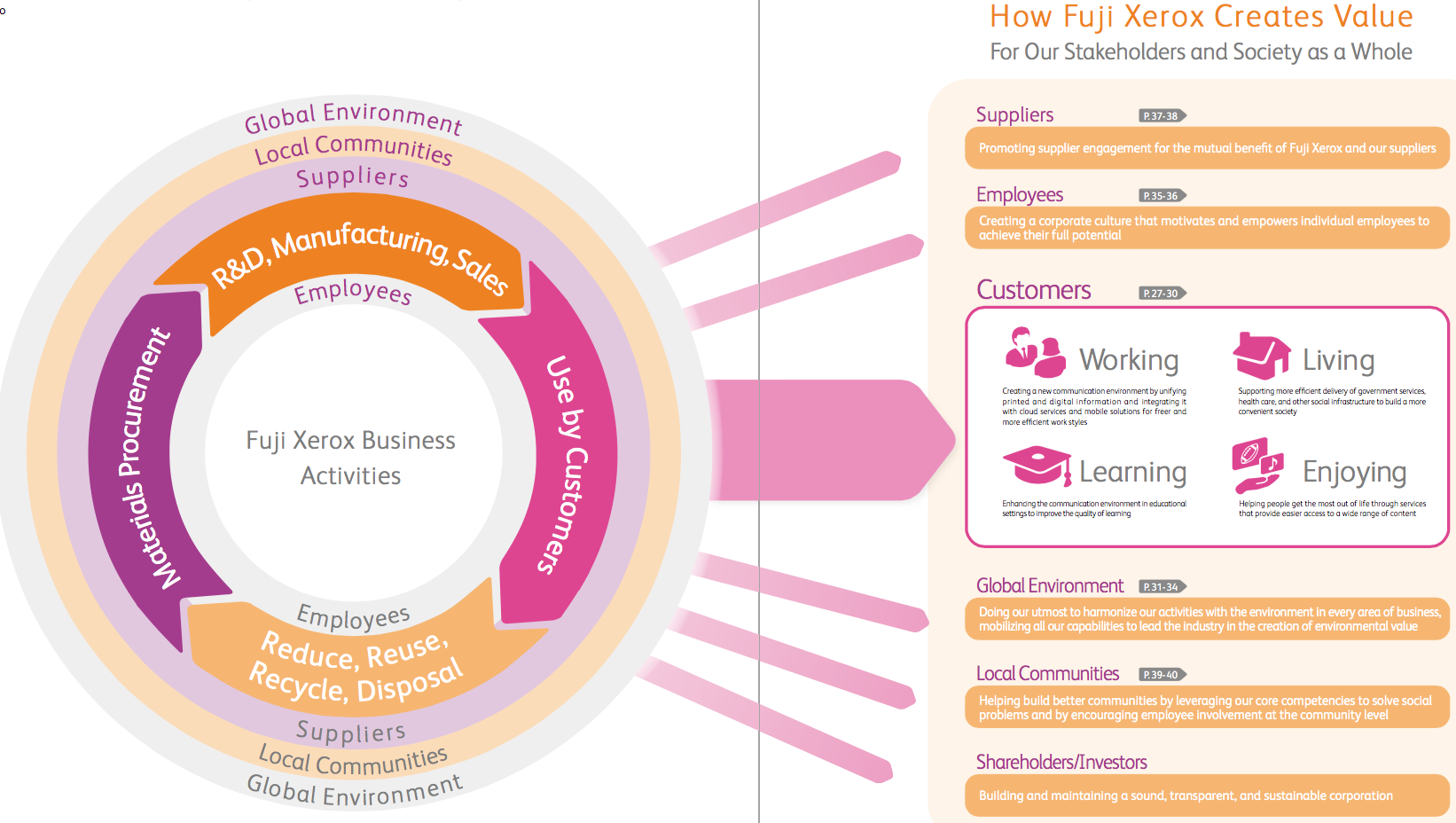

The company believes in “creating value for society throughout the value chain” (Figure 1). It considers the impact it has on society (both positive and negative) and the value it can provide for its stakeholders through its business operations, from the procurement of materials and R&D to manufacturing, sale, use by customers, and, ultimately, the disposal of products.

Figure 1. Business Activities and Value Creation

Value is not something the company can unilaterally proclaim to have created; it is generated only when it is recognized as such by the company’s diverse stakeholders. And to ascertain what its stakeholders are thinking, it uses two approaches: “communication” and “monitoring.”

The company promotes communication and dialogue through its Sustainability Report, its website, and other channels. The Sustainability Report is a key tool not just for customers and prospective job applicants but also for current employees. The explanations of corporate policy and activities contained in the report can give employees a deeper awareness of society’s concerns and help them come up with new ideas for their respective workplaces, thereby enabling them to provide higher value to stakeholders.

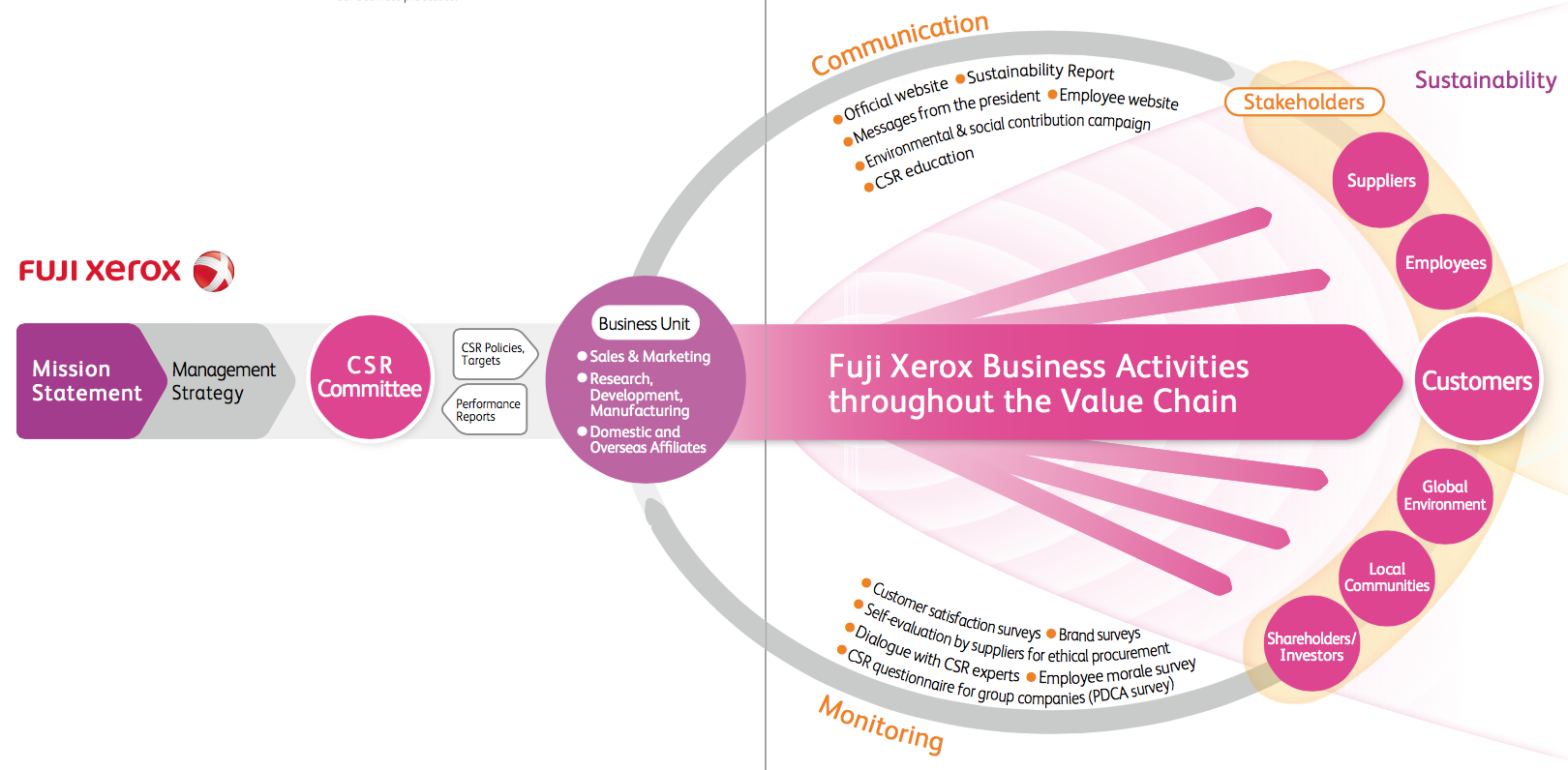

In the area of monitoring, Fuji Xerox is now taking steps to quantitatively measure the degree to which it is meeting the expectations and demands of stakeholders and also to reflect the results into management decisions in order to further develop its CSR management. The company regularly conducts customer satisfaction surveys, ethical procurement surveys targeting suppliers, dialogue between executives and outside CSR experts, employee satisfaction surveys, and CSR questionnaire surveys of group companies in Japan and overseas (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Communication and Monitoring for CSR Management

Communication and monitoring are extremely important in deepening the integration of business operations and CSR initiatives. The most difficult part of quantitatively measuring the degree to which the company is meeting society’s expectations is developing quantitative indicators for those expectations. They need to be adjusted in response to changing social expectations and in keeping with the company’s growth projections. The company needs to constantly scrutinize its relationship with various stakeholders, and it must adopt a long-term perspective.

Fuji Xerox calls these quantitative indices “CSR indicators.” The targets are set by the company’s CSR Committee, [3] progress toward them is reviewed by top management twice a year, and adjustments are made as necessary based on the PDCA cycle. The principal indicators are presented in the Sustainability Report in tables showing the results for previous years and goals for the year ahead with respect to six categories of stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, the global environment, local communities, and shareholders/investors.

Employees as Stakeholders

Let us look at the indicators for two of the six categories, namely, those relating to employees and to suppliers.

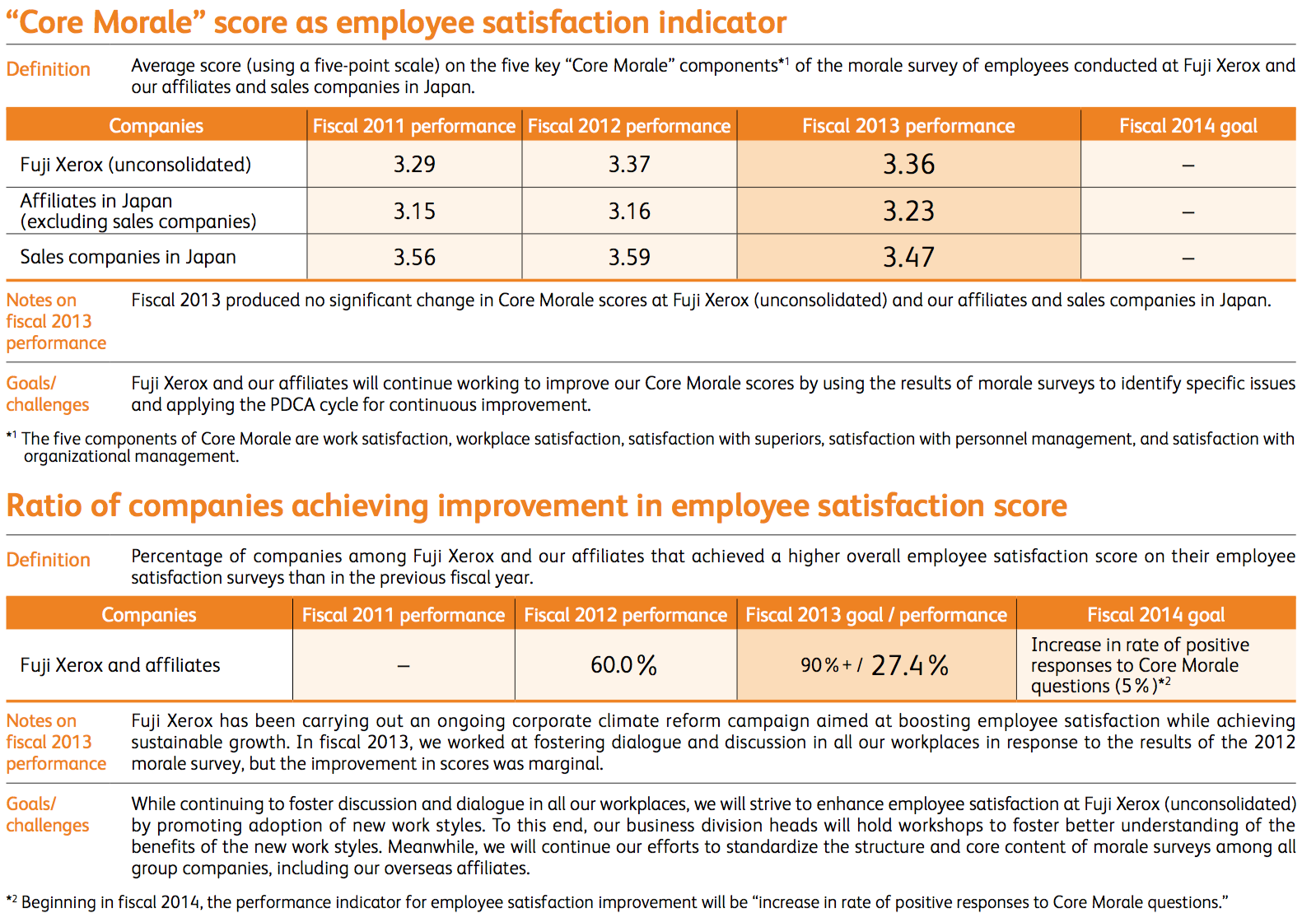

At Fuji Xerox, the stakeholder initiatives with the longest history are those targeting employees. The 2014 Sustainability Report presents six indicators for employees:

1. “Core Morale” as an indicator of employee satisfaction

- Average score (using a five-point scale) of the five key “Core Morale” components [4] of the employee satisfaction survey conducted at Fuji Xerox and its affiliates and sales companies in Japan.

2. Share of companies with improved employee satisfaction scores

- Percentage of Fuji Xerox group companies with a higher overall employee satisfaction score than in the previous fiscal year.

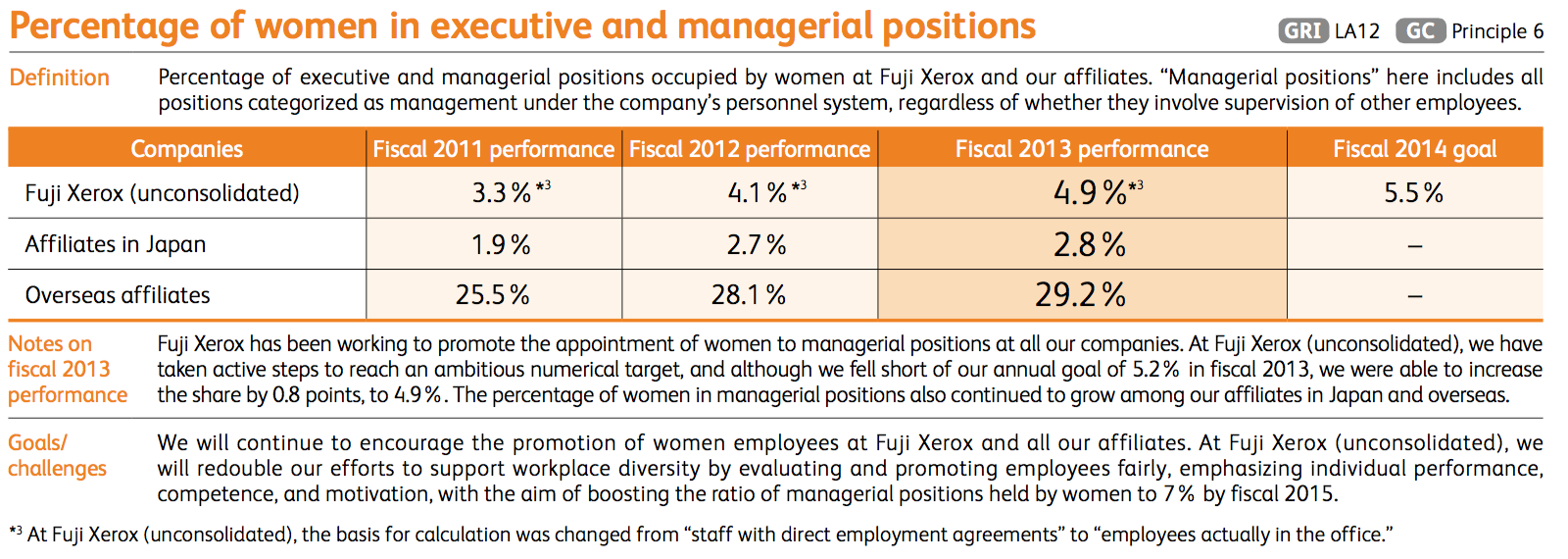

3. Percentage of women in executive and managerial positions

- Percentage of executive and managerial positions occupied by women at Fuji Xerox group companies.

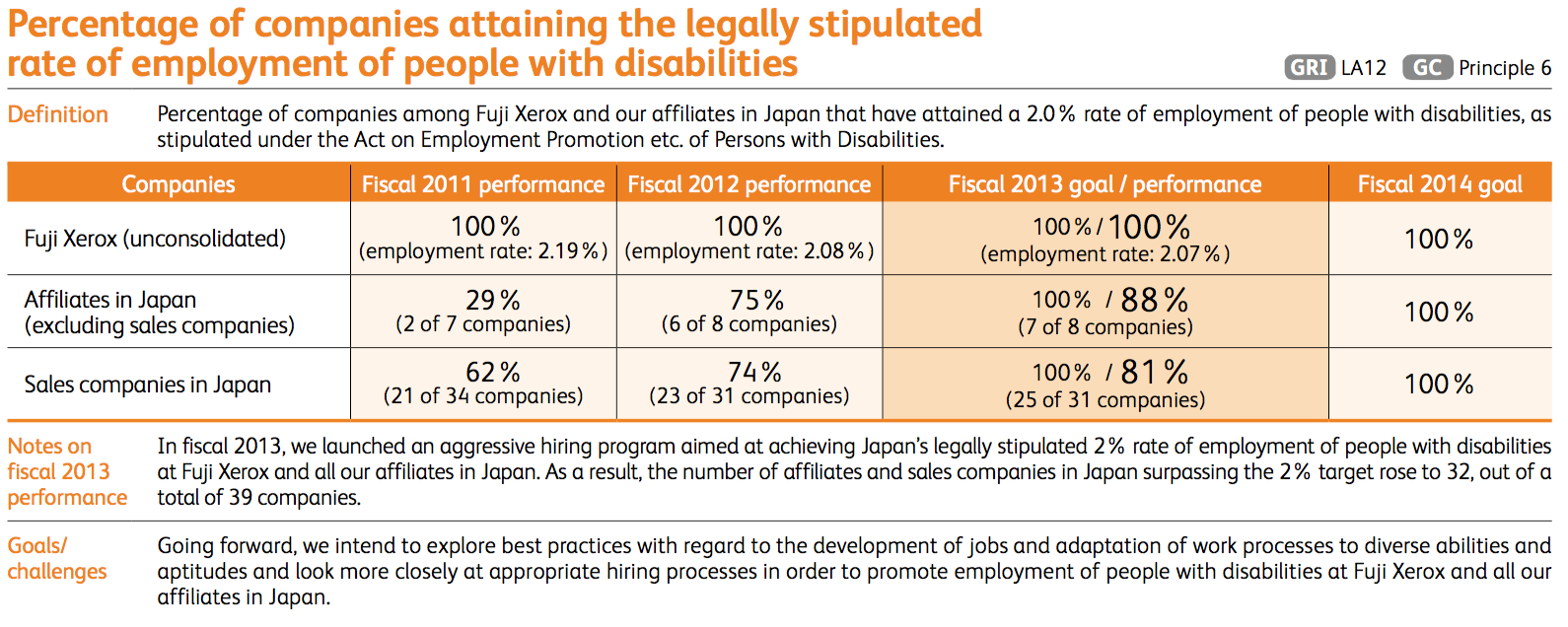

4. Percentage of companies clearing the legally stipulated rate of employment of people with disabilities

- Percentage of Fuji Xerox group companies in Japan whose rate of employment of people with disabilities is 2.0% or above, as stipulated by the Act on Employment Promotion etc. of Persons with Disabilities.

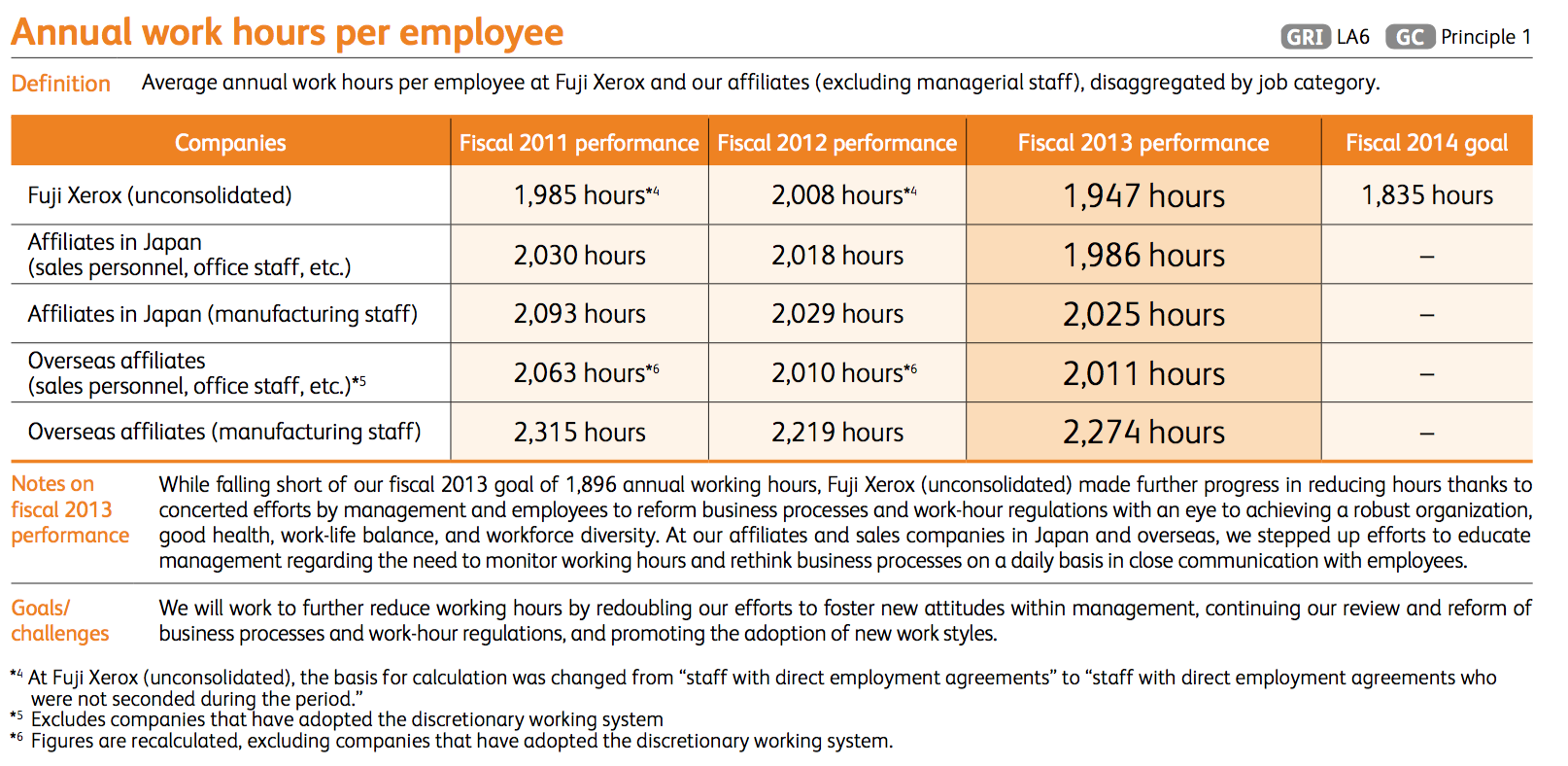

5. Annual work hours per employee

- Average annual work hours per employee (excluding managerial staff) at Fuji Xerox group companies, disaggregated by job category.

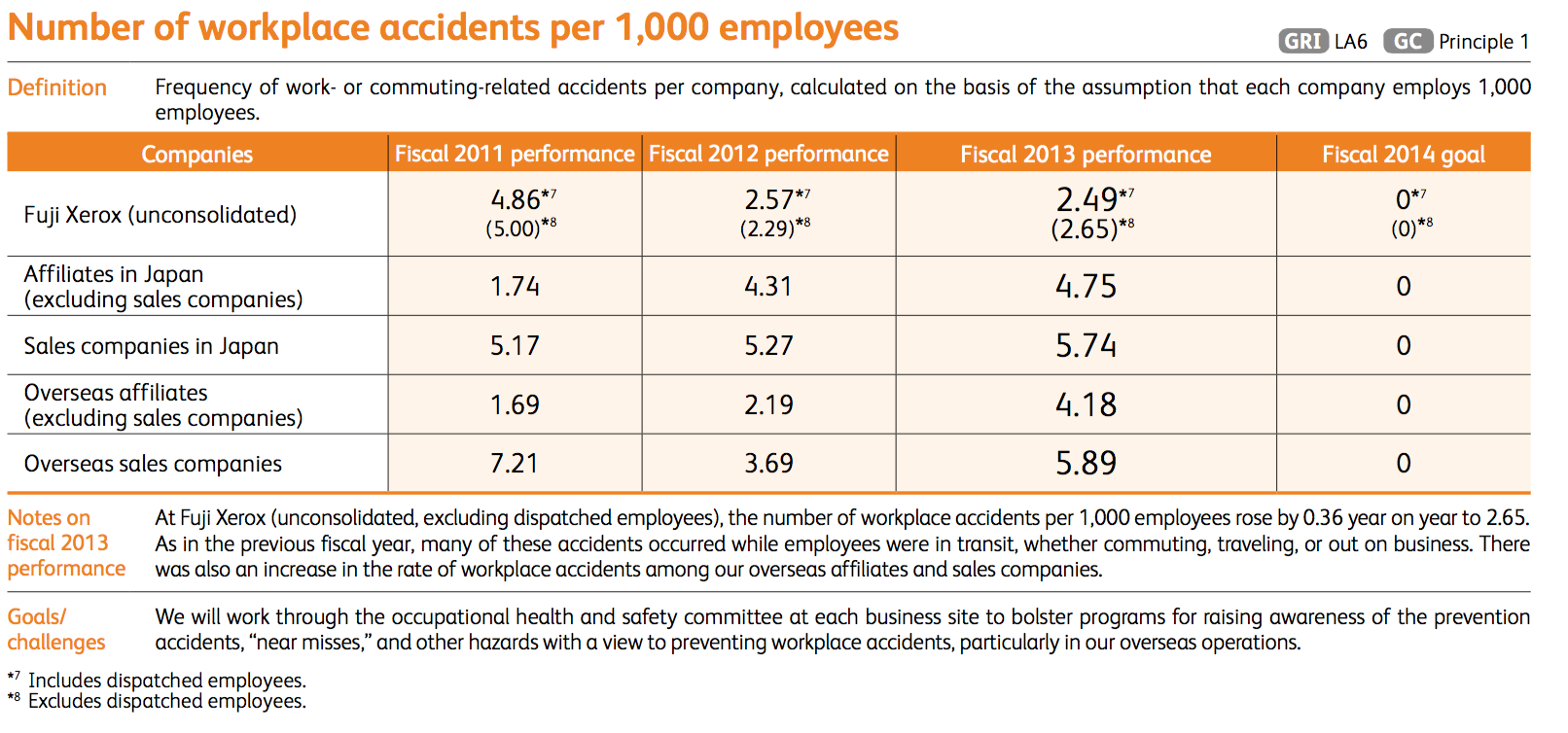

6. Number of workplace accidents per 1,000 employees

- Frequency of work- or commuting-related accidents at each company, converted into a ratio of accidents per 1,000 employees.

The scores for past fiscal years (April to March) and the goals for the year ahead are as indicated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Employee-Related CSR Indicators

The company does not set targets for the “Core Morale” indicator given the dangers that such goals can turn the “means” of ensuring worker satisfaction into an end in itself; it simply presents the data collected. For the other indicators, targets have been set by considering not just what would be ideal but also what would be even more ambitious in the light of actual improvements made to date.

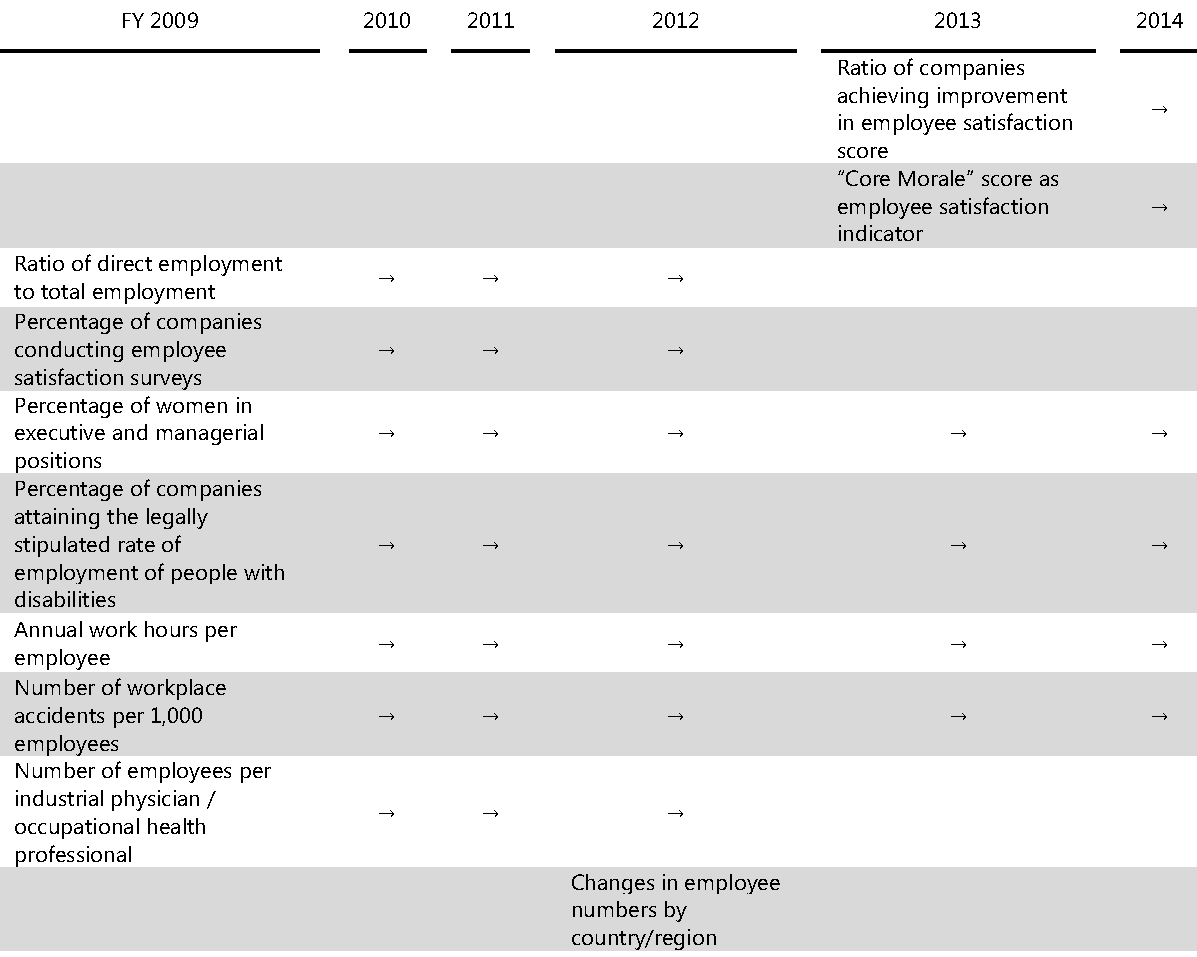

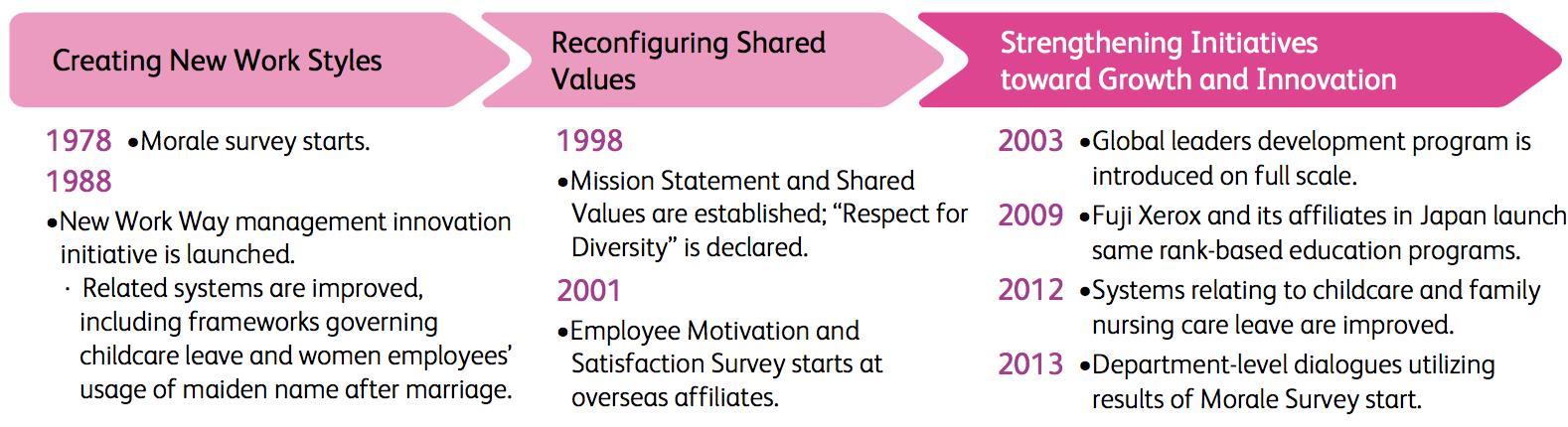

The indicators have also evolved over the years, and Figure 4 shows how the list has changed since 2009. Until 2012, for example, the CSR indicators looked at the percentage of group companies conducting employee satisfaction surveys; since 2013 they have measured the ratio of companies that have improved their employee satisfaction scores. The company has developed its CSR indicators in response both to changes in stakeholder perspectives and to advances in its own capabilities.

Figure 4. Changes in the Set of Employee-Related Indicators (Disclosed) by Year

It is interesting to note the presence of an indicator that was used a single year and then eliminated, suggesting how difficult it can be to find ways to quantify real conditions. An indicator provides just one perspective and cannot express an entire spectrum of settings. Taking this into account, Fuji Xerox constantly seeks to optimize its CSR indicators in keeping with changes in society and advances in its own capabilities.

These indicators represent key targets for the management and operation departments responsible for each type of stakeholder. The role of the CSR department is to provide opportunities for other divisions to directly perceive society’s changing needs, such as through stakeholder dialogue, and to support their setting of goals. Needless to say, the underlying intent is for each department to deepen its own awareness of society’s needs and to come up with its respective ideas, implement innovations, and provide greater value to stakeholders.

Building a Distinct Corporate Culture

“Core Morale” has a history dating back to 1978, when the company implemented an employee satisfaction survey, and was updated with the announcement of the “New Work Way” in 1988. Yotaro Kobayashi, who had become company president by that time, presents his ideas in a number of publications. [5]

Fuji Xerox was established in 1962 as a joint venture between Rank Xerox Ltd. (whose name was changed to Xerox Ltd. on October 31, 1997) and Fuji Photo Film Co. It was originally charged with disseminating and selling [6] US-made Xerox products, but in 1971 it added a manufacturing function aimed at making products matching the conditions in the Japanese market, which differed from those in the US and European markets. Iwatsuki Photo Optical Works Co., an affiliate of Fuji Photo Optical, was transferred to Fuji Xerox as the Iwatsuki Plant. Different corporate cultures were brought together in the new company. In order to create a distinct culture for Fuji Xerox as a manufacturing and sales company and to compete with rivals on the quality front, in 1976 the company embraced the concept of “total quality control.”

Fundamentally, TQC is a process of solving problems using scientific management methods based on the implementation of the PDCA cycle. In addressing a problem, the cycle begins with a “why.” To answer the question, managers “plan” a set of measures to resolve it, “do” the implementation of those measures, “check” the results, and “act” on ways to improve remaining issues. To get to the root of a problem, the cycle needs to be implemented five times, starting with a new “why” each time, until the true, underlying cause is found.

TQC was intended to create a universal language for the new manufacturing-and-sales company—as a distinct entity from the companies that created it—and thereby to change how individual employees work, how they function as a team, and how the company operates.

In 1978 Fuji Xerox marketed the FX 3500, a medium-speed copier to compete against the improved products of its rivals. Thanks to TQC, the company succeeded in shortening its four-year lead time to two years. And in 1980 Fuji Xerox won the Deming Prize, representing the pinnacle of TQC achievement. According to Kobayashi, the company intended to seek the Japan Quality Medal (now the Deming Grand Prize), awarded to companies that have implemented TQC for five years or more [7] after winning the Deming Prize and achieved substantial improvements in their quality management. But, as Kobayashi recalls, TQC had unexpected side effects.

Implementing the PDCA cycle five times was the standard approach to TQC, but Kobayashi reports that people began making excuses—putting off the effort to find the underlying causes because there was no time for a five-cycle run. The “five times” rule had taken on a life of its own and was discouraging attempts to find answers. TQC failed to produce significant results for some time thereafter, and Fuji Xerox stagnated.

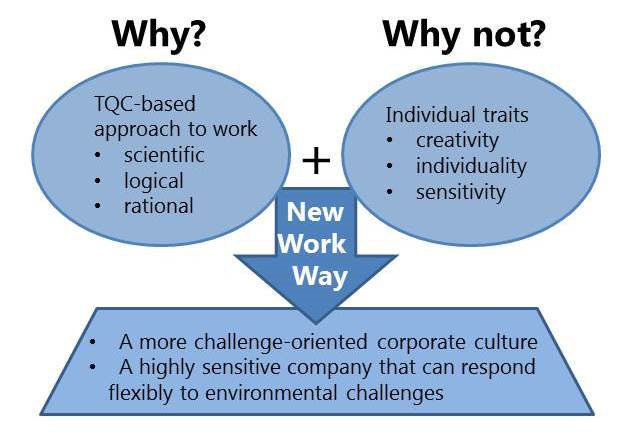

Kobayashi’s response was to introduce the New Work Way. While TQC focused on “why,” the New Work Way asked “why not”—an incitement, in other words, to at least make an attempt to change the status quo. The importance of “why” continued to be recognized, but with the New Work Way, Fuji Xerox sought to create a corporate culture and work style that would focus on both the search for deeper, root causes and a commitment to action (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The Basic Approach of the “New Work Way”

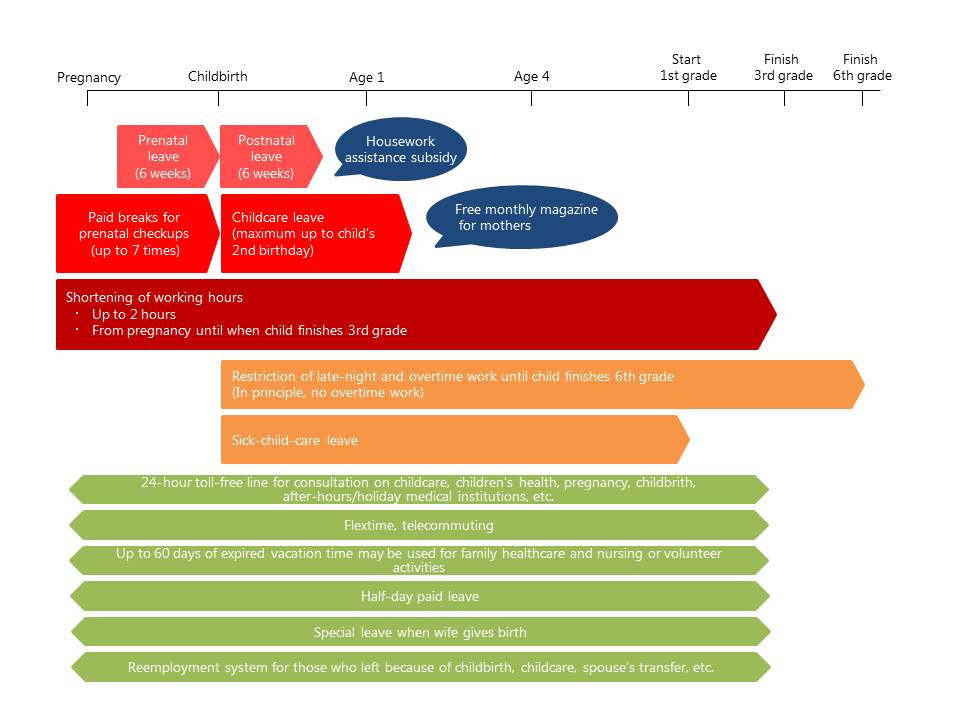

Under the New Work Way, Fuji Xerox experimented with new job arrangements, such as working at satellite offices and at home. It also took the lead over other companies in introducing programs for childcare leave (adopted in 1988, Figure 6) and nursing care leave (adopted in 1990).

Figure 6. Childcare Leave Arrangements at Fuji Xerox

Underlying Fuji Xerox’s efforts to fully draw out its employees’ potential and allow them to achieve growth is its adherence to the “Good Company Concept.”

For Fuji Xerox, a “good company” has three attributes (Figure 7): It is a “strong” company able to satisfy customers and shareholders by developing and marketing outstanding products and maintaining competitiveness. It is “kind” to the environment and to local and global communities. And it is an “interesting” company where employees find work fulfilling. These attributes may not seem unusual, but setting them forth in concrete terms is a form of communication with stakeholders and is an expression of the company’s ongoing efforts to monitor society’s expectations and to make ongoing improvements.

Figure 7. Fuji Xerox’s “Good Company” Concept (announced in 1992)

Engaging with Suppliers

Let us now look at a second category of Fuji Xerox’s CSR indicators, namely, those relating to suppliers. This is an area in which the company has achieved rapid progress.

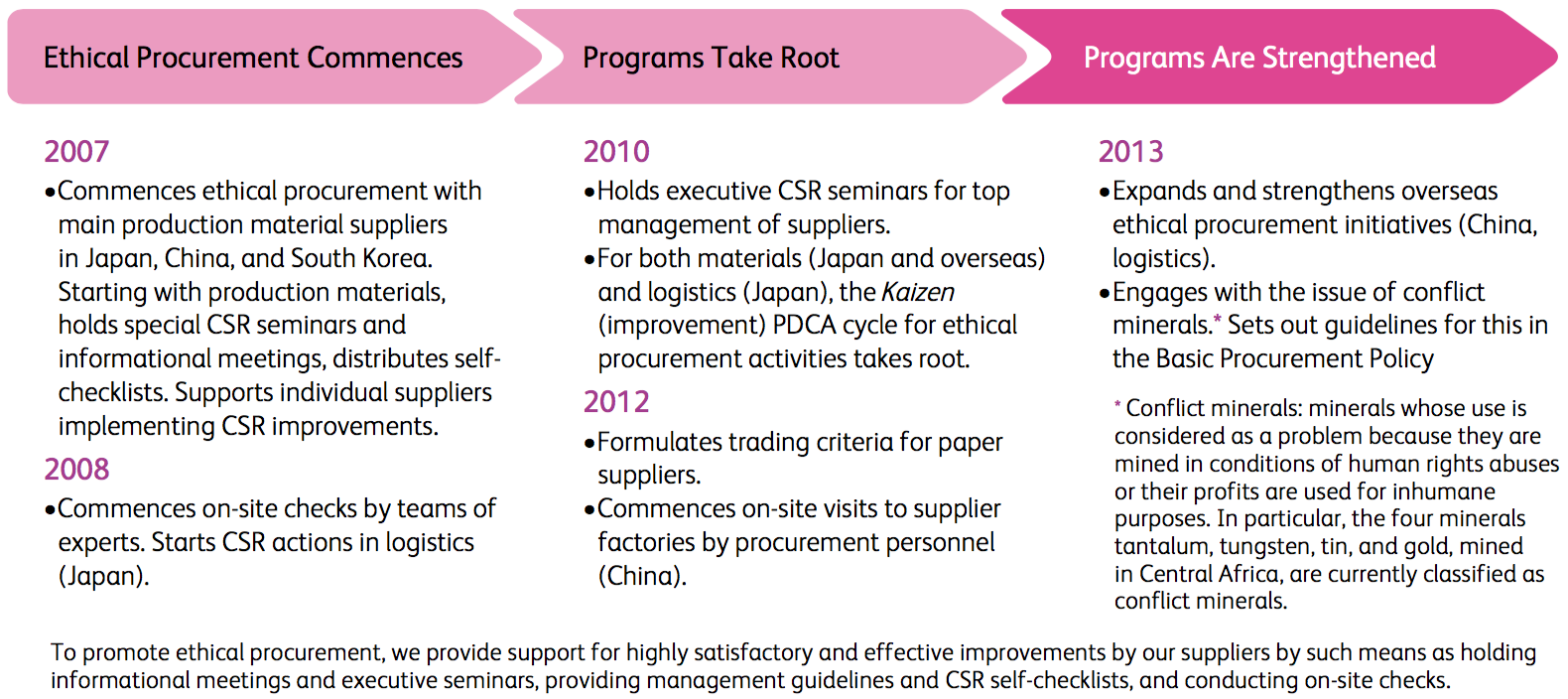

Many readers, seeing Fuji Xerox’s approach toward employees, may assume that CSR requires cumulative efforts over a long period as well as excellent management; this may discourage other companies from attempting to catch up. But Fuji Xerox’s initiatives toward suppliers began in 2007. Developing and deepening CSR does not necessarily require a long history; a glance at the steps taken by Fuji Xerox toward suppliers show how far a company can get in less than a decade through meticulous, honest effort. It can also reveal what the company is doing now to further develop its CSR.

The essence of Fuji Xerox’s engagement with suppliers is “ethical procurement”—presenting suppliers with procurement standards that include CSR-related elements and seeking their strict compliance with those standards.

When Fuji Xerox was contemplating moves toward ethical procurement, it faced three issues. One was a series of inquiries about such a program from US and European clients, who noted that this would be a factor in whether or not they continued to purchase from the company. The inquiries were forwarded to the CSR department, which pointed to the establishment of the Electronic Industry Code of Conduct by companies like Dell and IBM. This was a powerful impetus toward the adoption of ethical procurement.

A second issue was the European Union’s adoption of the Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive, which came into effect in 2006. Coping with this directive was the top priority of Fuji Xerox’s procurement department at the time, and ethical procurement was widely viewed as a matter for future consideration.

The third was the rising demands on suppliers for quality, cost, and deadlines (QCD) in the face of intensifying market competition. Many of Fuji Xerox’s suppliers were small and midsize businesses that lacked the leeway to adequately meet new procurement standards, thus heightening QCD-related risks.

The ethical procurement project team, set up jointly by the procurement and CSR departments, thus faced a difficult set of questions: How should Fuji Xerox advance ethical procurement? How should it be positioned vis-à-vis QCD, which had a direct impact on the company’s competitiveness? And in terms of priority, should it come before or after measures to cope with the RoHS Directive?

The project team ultimately decided that (1) ethical procurement is an inevitable trend, something that will eventually become a matter of course, and (2) rather than simply presenting suppliers with demands, the company should undertake ethical procurement in a manner that would be beneficial to suppliers as well.

The company sums up this thinking as follows: “At Fuji Xerox, . . . we share goals and develop shared values with suppliers by deepening mutual understanding. We call this approach ‘supplier engagement.’ When the action plan was proposed in 2007, President Yamamoto (then executive vice-president) said that the basic approach must be to pursue win-win relations with suppliers and that implementation of the program must not be dictated by the convenience of Fuji Xerox. To achieve the required QCD, reliable supply, and flexible adjustment of manufacturing systems, it is absolutely essential that supplier capacity be raised and cooperative relations developed. There is no benefit for Fuji Xerox if we fail to develop shared values that strengthen both Fuji Xerox and its suppliers.” [8] This philosophy continues to underlie the company’s ethical procurement today.

This policy was turned into more concrete form through cooperation with suppliers. In June 2006 the ethical procurement project team held its first CSR study meeting with a group of Fuji Xerox’s key transaction partners. The theme of the meeting was ethical procurement, and suppliers were asked how this could be implemented in a way that would be useful for them.

Toshiaki Ota, representative director of Kinjo Rubber Co., who participated in the meeting, commented: “This concept is something that is definitely necessary for our survival even if Fuji Xerox hadn’t approached us. I appreciate the fact that Fuji Xerox gave us the opportunity to think about this together. We will need to make an all-out effort regarding quality, cost, and the CSR activities that we have learned here today. That is the type of business environment in which we find ourselves today. The managing member companies . . . [of this group] must take the initiative and expand these activities to include other member companies.” [9] Needless to say, this strong endorsement helped convince Fuji Xerox to embrace ethical procurement.

After a series of meetings, the group identified a number of common issues, such as production and shipment stoppages resulting from labor disputes at overseas sites. At the time, about 80% of Fuji Xerox’s production was being carried out in China, and many of the group’s managing member companies also had production plants in China. Steady progress was being made with respect to environmental issues there, but less visible was the situation regarding human rights and labor issues. To gain a clearer picture, the group held a meeting in Shenzhen, China, in November 2006.

In Shenzhen, members of Fuji Xerox’s ethical procurement project team and representatives of the study group’s managing member companies learned much at the Institute of Contemporary Observation, a nonprofit organization specializing in labor issues in China. They gained the shared perception that continuing with the current system of labor management would eventually make it impossible to hire talented workers and jeopardize the continuation of their operations. Instead of conducting simple yes/no checks, there was a need to adopt ethical procurement standards that would lead to concrete solutions, hedge against risks, and provide advice that would lead to direct improvements. Fuji Xerox became convinced that this sort of approach would result in ethical procurement matching the ideas of cooperating with suppliers and creating a program that would be useful for them—and that would also befit Fuji Xerox’s corporate character.

The project team made a list of the expectations of society’s various stakeholders, taking note of such existing guidelines as the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition Code of Conduct, ISO 26000, and the UN Global Compact, as well as of the dialogue it had conducted up to that point:

- Items related to laws and regulations (highest priority): Areas in which noncompliance would likely threaten the company’s business or survival or result in an order to suspend operations from regulators or government authorities

- Items related to laws and regulations (high priority): Areas in which noncompliance would likely result in strong warnings or notices from regulators or government authorities or social sanctions, such as consumer boycotts

- Items related to laws and regulations (medium importance): Areas in which noncompliance may result in warnings or notices from regulators or government authorities and pose the risk of damage or other impacts to company management, even if resolved

- Other items: Items not enshrined in laws or regulations but are required by society

Regarding “other items,” Fuji Xerox drew up an ethical procurement checklist with the idea of having suppliers provide information in advance concerning matters that may eventually require responses in the light of moves by nongovernmental and nonprofit organizations. This checklist, confirming compliance with the suppliers’ code of conduct, included more than 300 items. In preparing and sharing this checklist, Fuji Xerox provided detailed background explanations of emerging CSR-related social issues, since the aim was not just to have suppliers submit reports but to have them fully understand the significance of each item and to take the appropriate next steps based on this understanding. There was no point in collecting a set of documents that were signed by suppliers without their full understanding of the contents. The checklist, after all, was a tool to encourage further action, bring mutual benefits to Fuji Xerox and its suppliers, and to enhance competitiveness while fulfilling social responsibilities.

In addition to monitoring suppliers based on the checklist, Fuji Xerox sent teams of experts for on-site checks to suppliers that seemed to have major issues or presented possible future risks. These teams consisted of members of the procurement, personnel, environmental, general affairs, legal, and CSR departments who had not only practical experience in various positions but also expertise in their respective fields of responsibility. At the outset of each visit, the procurement department representative explained that the on-site check was being implemented for the benefit of the supplier itself. The team requested that the supplier’s top executives, such as the president and executive vice-president, participate in the process. The team members visited offices, plants, and even dormitories to see and learn about the situation for themselves—rather than simply relying on the supplier’s self-assessed checklist. Sometimes the members looked at areas like the management of factory personnel and the safety of dormitories. While the process was called on-site checking, the team’s real mission was to enable suppliers to address their own problems. Inspections by other companies might end with a check for regulatory violations and the conveying of the findings. But Fuji Xerox inspectors did not stop there. They had their own experience and knowledge to draw on with respect to issues like relations with local government officials and workers, and they were able to offer practical advice about possible solutions, sharing stories about how they overcame similar problems in their own work.

To repeat, the purpose of Fuji Xerox’s ethical procurement program was not to inspect or monitor; even if a supplier fell short in some respects, a path was offered for continued relations if it had the will to implement improvements. And if it did, the company would work with the supplier to achieve a win-win outcome. This approach, originally launched jointly by the CSR and procurement departments, has become standard practice in the procurement department. Many in the department have gained a deeper appreciation of the essence of CSR, namely, that ethical procurement and QCD—which were previously seen as separate entities—actually have the same objective. “When we visit suppliers,” explains a member of Fuji Xerox China’s procurement department, “the executives listen closely to what we say. Our job is to secure a steady flow of high-quality products from them. And for this, we need to understand the supplier’s management philosophy as well.”

Such heightened awareness comes from the same source that produced the checklists on which Fuji Xerox’s quantitative CSR indicators are based and that continues to drive the company’s determination to further develop and deepen its CSR initiatives. Such resolve becomes meaningful when it is embraced not just by specific, CSR-related departments but in the day-to-day operations of workplaces throughout the company.

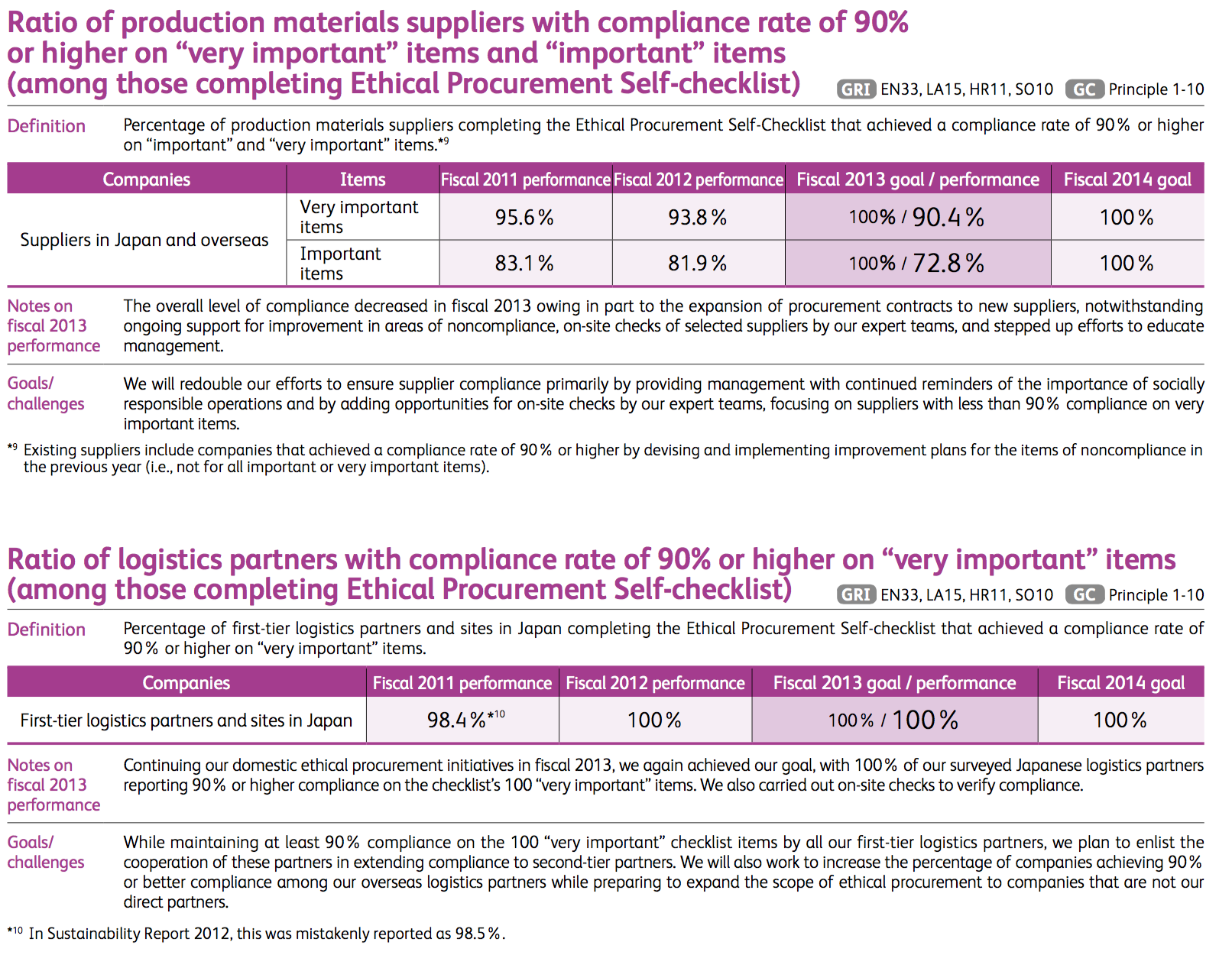

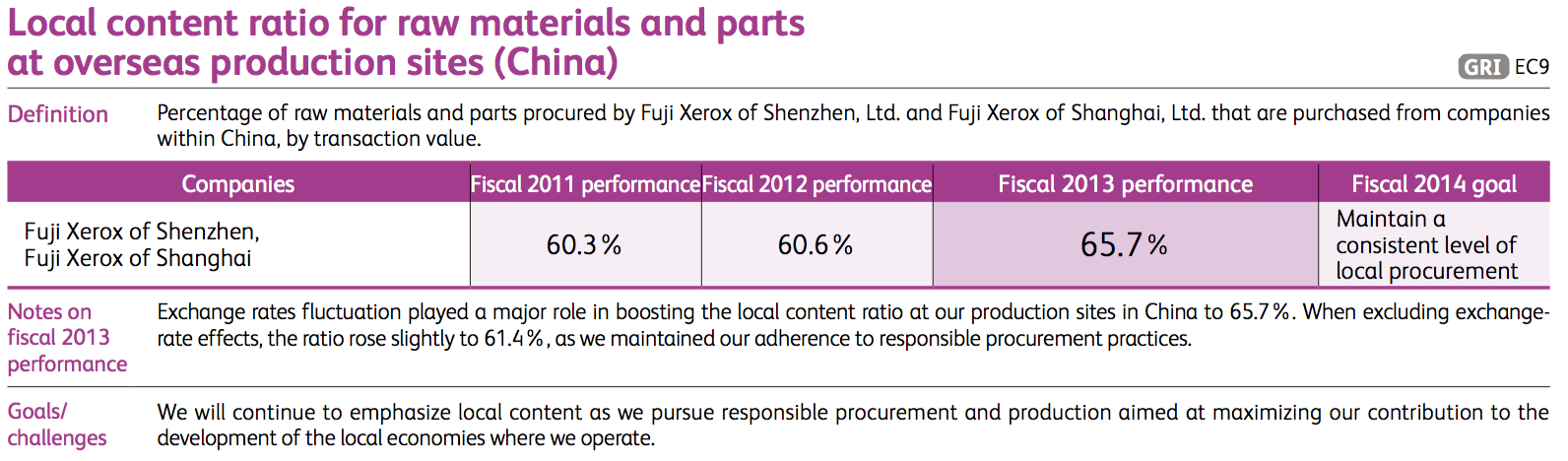

In concluding this section, let us look at Fuji Xerox’s CSR indicators relating to suppliers, as presented in its 2014 Sustainability Report (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Supplier-Related CSR Indicators

Above we looked at the evolution of Fuji Xerox’s ethical procurement. The company now uses five indicators, arranged by value chain and social issues: production materials, logistics, paper supplies, conflict minerals, and local content.

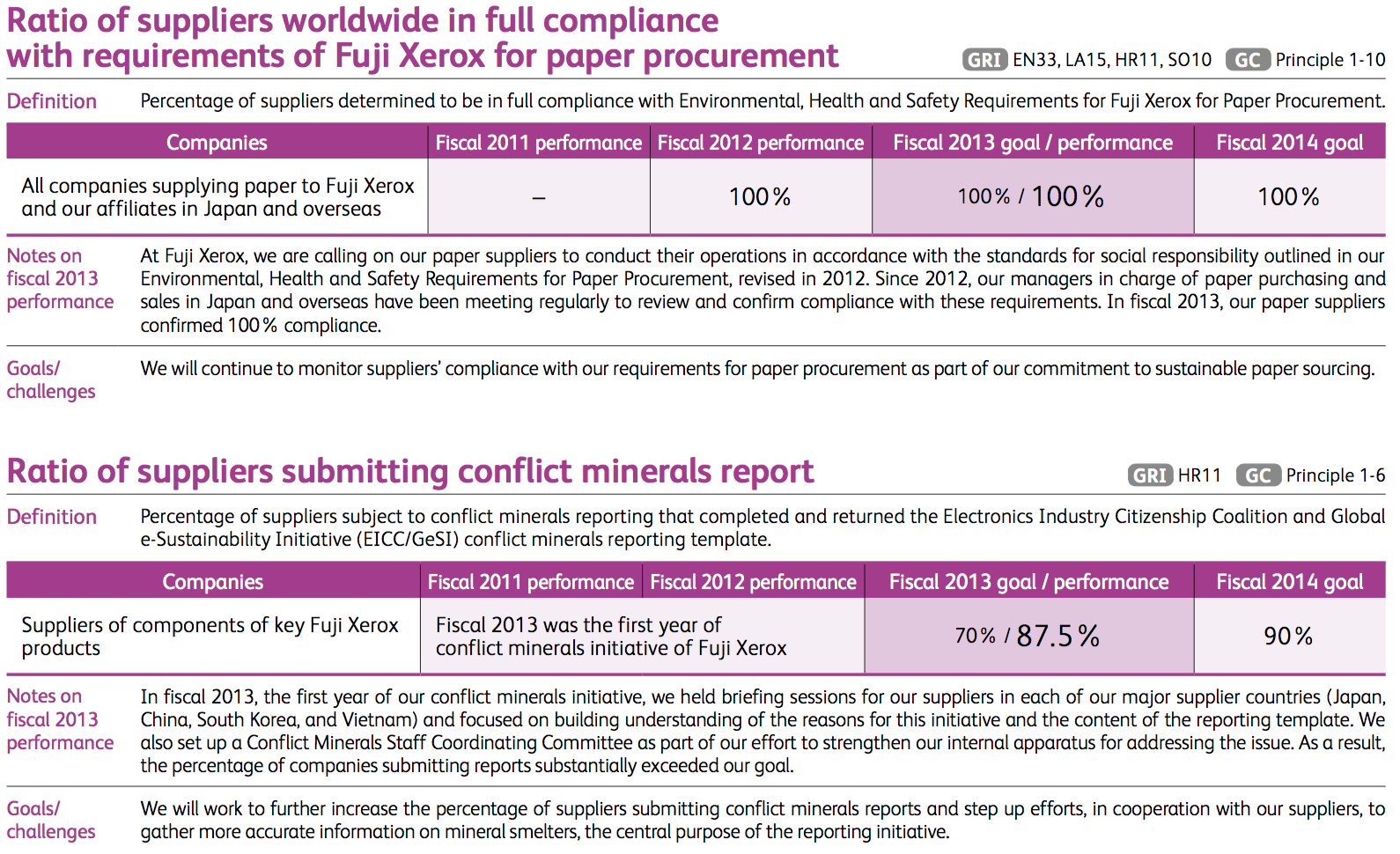

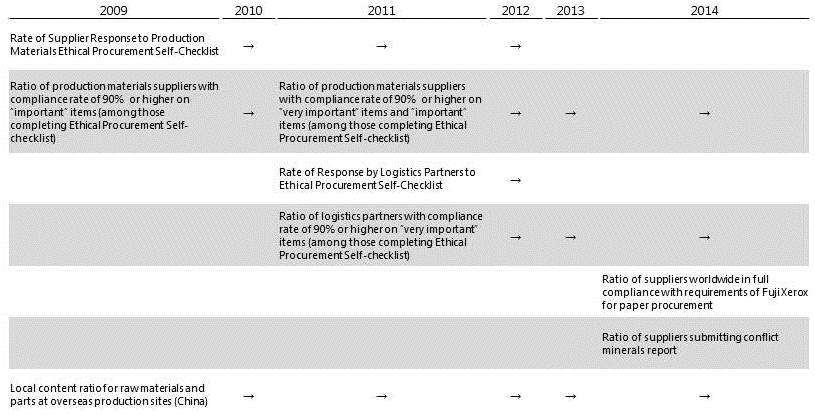

As the company’s initiatives advanced, the indicators themselves have undergone renewal, as indicated by the changes in the set of indicators over the years (Figure 9). What began with a self-assessment checklist and the rate of response later led to a closer examination of the checklist’s content, as demonstrated by the addition in 2014 of an indicator for conflict minerals.

Figure 9. Changes in the Set of Supplier-Related Indicators (Disclosed) by Year

Diligent, Cumulative Effort

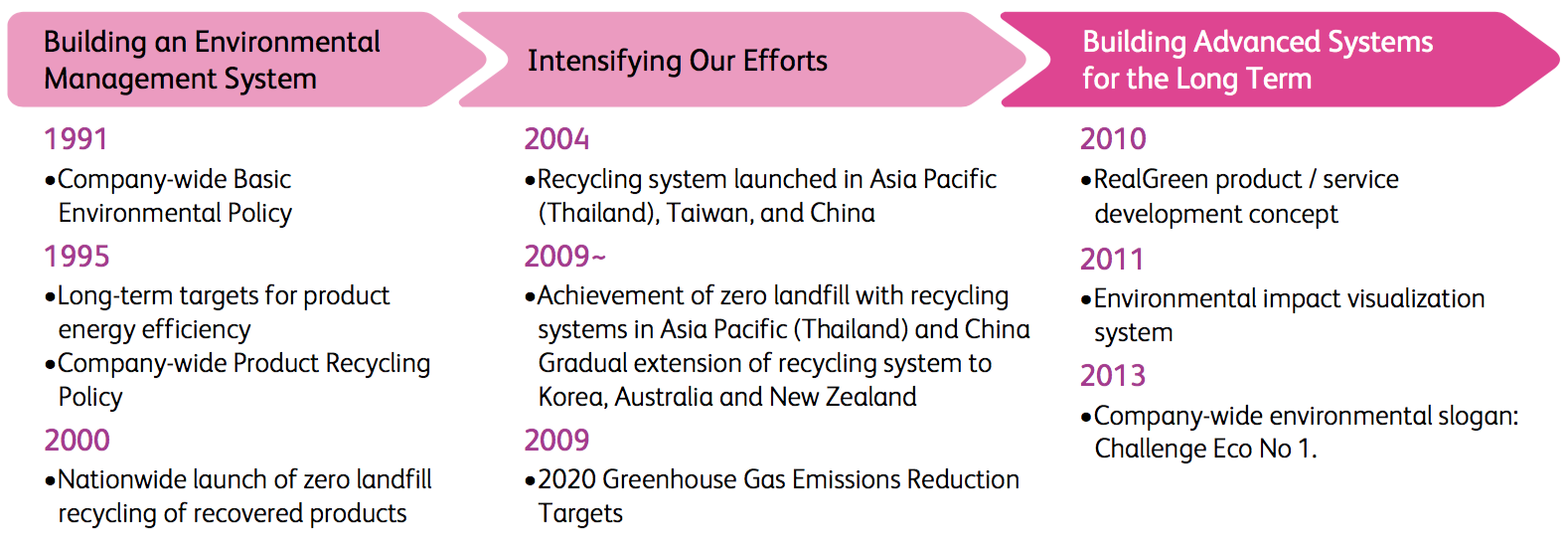

One difference between the sustainability reports of Fuji Xerox and other companies is that Fuji Xerox clearly presents the course of its progress and its current position in each area of CSR (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Progress of CSR at Fuji Xerox

Engagement with Global Environment

Engagement with Employees

Engagement with Suppliers

Engagement with Local Communities

The timeframes for the various CSR initiatives differ, with some starting back in the 1970s and others beginning less than 10 years ago. But progress can be seen in all fields. Fuji Xerox indicates where it stands now based on a record of their concrete accomplishments and in the context of major social trends.

The same is true of the CSR indicators described above. They have been carefully developed to express as accurately as possible the actual state of key management concerns at Fuji Xerox. Only through such diligent, cumulative effort has it been possible to quantify the progress being made in each area.

Some have attributed Fuji Xerox’s CSR accomplishments to the company’s prescient executive leadership or the liberal corporate culture of foreign-owned companies. Readers of this report will no doubt realize that this is an oversimplification. In fact, people who voice these mistaken views about the source of Fuji Xerox’s success often use them as excuses for their own companies’ lack of similar progress, pointing their finger at structural factors rather than at their own lack of effort.

An outstanding chief executive may indeed be important. But having a charismatic leader alone is not enough to push CSR forward, let alone to turn CSR into the guiding principle of corporate management, business operations, and individual projects.

At Fuji Xerox, everyone from the chief executive to the rank and file has an accurate grasp of CSR. They are able to articulate how CSR is an integral component of their business. CSR has meaning only if a company’s raison d’être and the value it creates are recognized by society. Just as society constantly undergoes change, the company, too, must be flexible enough to adapt to those changes. These concepts are fundamental to CSR, and it would appear that Fuji Xerox employees have a deep understanding of them.

They also understand that CSR is just not a matter of definitions, principles, or management philosophies; more important is implementation, putting the ideals into practice in their respective workplaces. This is a mutually reinforcing process wherein individual CSR initiatives can grow and evolve together with the company’s business operations, as well as further deepen employees’ awareness of CSR.

CSR at Fuji Xerox is being advanced through such diligent efforts by individual employees to integrate the ideals of CSR into everyday business operations.

APPENDIX

Excerpts from President Tadahito Yamamoto’s “Top Commitment” Message (Fuji Xerox Sustainability Report 2014)

1. CSR: Synonymous with Corporate Management

Fuji Xerox is acting swiftly to globalize all its activities, including development, manufacturing, and sales, with the aim of achieving sustained growth. While global business development presents many new opportunities, it also comes with various risks. Differences in commercial practices as well as labor laws and practices and interactions with overseas suppliers can at times lead to unintended involvement in environmental destruction and human rights violations. With the development of information and communication technologies (ICT), the expansion of socially responsible investment (SRI) funds, and the integration of environmental, social, governance (ESG) issues into investment, both society and investors are more rigorously monitoring the activities of businesses. Companies are now expected to recognize that they are accountable for their entire value chain, including all upstream and downstream activities, and to pay careful attention to environmental and social factors in their operations.

At Fuji Xerox, we find our calling in document services and communications. Our primary objectives are to assist customers in creating value and to contribute to the progress of society by providing an environment for valuable communications. Our Mission Statement commits us to “Build an environment for the creation and effective utilization of knowledge,” “Contribute to the advancement of the global community by continuously fostering mutual trust and enriching diverse cultures,” and “Achieve growth and fulfillment in both our professional and personal lives.” These three points are our CSR objectives. For Fuji Xerox, CSR is synonymous with corporate management and cannot be separated from our business pursuits. For us, CSR starts with insightful observation of social issues and extends to thoughtful reflection on how to deliver value to customers, how our actions impact stakeholders, and how to realize the vision of Fuji Xerox including our organizational culture.

Providing customers with outstanding products and services is an essential requirement for any business. No less important is the question of how to accomplish this. “Transforming business processes while making a firm commitment to stakeholders to uphold values that the company believes to be right” and implementing the necessary activities through “unity of words and deeds” ( genko-i t chi in Japanese) pose an enormous challenge, particularly in light of the broad range of issues related to quality and cost competitiveness. Regardless of the difficulty of this challenge, we at Fuji Xerox understand this to be an indispensable part of becoming an Excellent Company that is truly cherished by its customers.

2. Integrating CSR with Our Core Business

I believe that significant changes have to be made to establish CSR as an integral part of corporate culture at Fuji Xerox. All business processes and work styles at the front lines of our business must be transformed with an eye to CSR values, and we must create an environment in which all corporate activities are assessed and executed from the perspective of whether or not they contribute to delivering value to stakeholders. . . .

Goals established by management are embedded in frontline plans for product development, procurement, manufacturing, sales, and other activities. As I have been emphasizing, it is critically important to clarify the link between CSR and the mission and objectives of each organization and to achieve a full integration between CSR and our core business. By helping us obtain new technologies, develop attractive products and services, and strengthen cost competitiveness, I believe the integration of CSR and our core business activities is key to creating a new awareness within the company as we pursue our principal business and to changing work processes. My ultimate objective is to create a situation in which each employee realizes the social significance of the work that he or she is performing and CSR management evolves in a natural and self-sustaining way.

[1] See the appendix at the end of this document.

[2] This exposition is similar to the definition of CSR as revealed in the Tokyo Foundation’s 2014 CSR White Paper.

[3] Fuji Xerox established the CSR Committee in April 2010 as part of its effort to fully integrate CSR into its business operations. This is one of several function-based committees under the board of directors and the corporate executive committee that serve as decision-making bodies for management in particular areas.

[4] Work satisfaction, workplace satisfaction, satisfaction with superiors, satisfaction with personnel management, and satisfaction with organizational management.

[5] Works referred include the transcript of a presentation titled “Kore kara no kigyo keiei” (The Future of Corporate Management) by Yotaro Kobayashi and Akira Miyahara and the article “’Jibun ni shojiki de are’: Seizensetsu no keiei, Kobayashi Yotaro no 50 nen” (“Be Honest to Yourself”: Yotaro Kobayashi’s 50 Years of Good-by-Nature-Theory Management), Purejidento ( President ), May 14, 2012.

[6] Strictly speaking, the joint venture was disseminating Xerox products through rentals. This method, which facilitated the use of costly copying machines for customers, had been adopted and found successful by all the Xerox group companies around the world.

[7] Changed to “three years or more” in 2000.

[8] Sustainability Report 2013, p. 17.

[9] Sustainability Report 2007, p. 18.