- Article

- Tax & Social Security Reform

What a Border Adjustment Tax Will and Will Not Do

April 6, 2017

Often mistakenly considered a protectionist measure, a border adjustment tax, argues Takeo Hoshi, is actually not a trade-distorting mechanism but part of an attempt at fundamental tax reform with a sound economic foundation.

* * *

Two months have passed since Donald Trump entered the White House, and the direction of his international economic policies is gradually becoming clearer. On his first full day in office, he signed a presidential order pulling the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, strategically steering the country away from multinational trade agreements—through which the United States had led the way in writing the rules of international commerce—and toward bilateral pacts with the aim of giving the country an advantage over foreign competitors.

Often considered part of this more protectionist approach is the administration’s push to introduce what is known as a border adjustment tax, which the Republican Party has been advocating. Trump himself initially rejected the tax as being too complex but has recently begun to support it. Because the tax is applied to imports but not to exports, some see it as a mercantilist tool to promote sales of domestic goods and services in overseas markets while keeping out imports. Should Washington embrace such a tax, other governments may be prompted to reciprocate with protectionist policies of their own, raising the specter of shrinking global trade.

Is It Really Protectionist?

On closer inspection, though, the border adjustment tax is actually not a trade-distorting mechanism but part of fundamental tax reform. This article will examine the implications of this tax using a number of simple, hypothetical examples. The impetus for such an examination was provided by a series of articles authored by members of the Tokyo Foundation’s Tax and Social Security Policy Committee (Japanese only), led by Senior Fellow Shigeki Morinobu.

The border adjustment tax, properly speaking, is part of a “destination-based cash flow tax” (DBCFT). As the name suggests, there are two basic components to the DBCFT.

The first is the “destination-based” element, meaning that the tax is levied in the country of consumption rather than of origin. Japan’s consumption tax and other forms of value added taxes all follow this principle, as exports are untaxed, while imports are taxed. The tax now being debated in the United States is an attempt to apply the destination-based idea to corporate taxes.

The other is the “cash flow” element, which taxes the profits defined as actual receipts minus actual payments. One important difference of this approach from current corporate tax practices is that companies would be able to deduct the full amount spent on capital investment during that year, instead of depreciating it over the useful life of a tangible asset. By providing immediate relief, the DBCFT is likely to encourage corporate investment. Here, though, I will concentrate my discussion on the impact of the destination-based element of the tax.

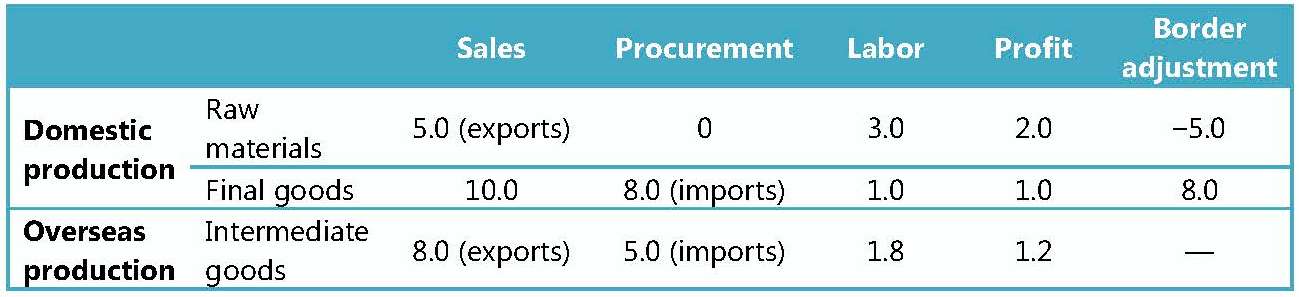

The destination-based element, as noted above, leads to “border adjustment,” inasmuch as the tax is applied to domestic consumption and excludes goods or services produced at home but are consumed abroad. To elucidate what this entails, let us see how the DBCFT would affect the after-tax income using a simple example of a vertically integrated corporate group with three stages of production, depicted in the table. We will first assume that the corporate tax rate is 20%.

(1) The material supply producer sells raw materials for $5 million, of which $3 million is paid as labor, leaving a profit of $2 million.

(2) The intermediate goods producer purchases the raw materials for $5 million and processes them into intermediate inputs worth $8 million. Workers are paid $1.8 million for a profit of $1.2 million.

(3) The final goods producer purchases the intermediate inputs for $8 million and assembles them into final goods, which are sold to consumers at $10 million, paying workers $1 million and registering a profit of $1 million.

Group Profit after Border Adjustment Tax ($ million)

Let us first look at what this corporate group would owe the tax authorities under the current corporate tax system. When all three stages of production take place domestically, the three companies would be required to pay 20% of their profits as corporate tax. Together, the three companies earn $4.2 million ($2 million + $1.2 million +$1 million) in profits. After paying 20%, they would be left with after-tax income of $3.36 ($4.2 million × 0.8).

Current System Encourages Multinationals to Move Offshore

How would the amount the group pays in taxes change if it chose to relocate its intermediate goods production to a country with a corporate tax rate of, say, 10%? The lower taxes would mean that the after-tax income of the group as a whole would now rise to $3.48 million ([$2 million +$1 million] × 0.8 + $1.2 million × 0.9). The group would thus have an incentive to move its operations overseas. In other words, the current US tax system has a distorting effect in encouraging multinationals to move to countries offering lower corporate tax rates.

The border adjustment tax can rectify the distortion by eliminating this incentive, as shown in the right-hand column of the table. If the group ships raw materials to the intermediate goods company located in a different country, the group’s tax base, adjusted at the border, would decline by $5 million (exports are not included in taxable revenue) and correspondingly rise by $8 million (imports are taxed) as the offshore affiliate ships the intermediate goods to be assembled and sold as final products. With a corporate tax rate of 20%, the group as a whole would see its after-tax income decline to $2.88 million ([$2 million + $1 million] ×0.8 – [$8 million − $5 million] × 0.2 + $1.2 million × 0.9) despite a lower corporate rate for the intermediate goods company. Note that the second term of the equation represents the border adjustment tax.

As the example shows, a border adjustment tax will eliminate the financial benefits of relocating abroad, as companies will gain nothing from the lower tax rates in other countries.

The same goes for countries where lower wage levels prevail. To see this, let us consider a case where the corporate group can benefit from lower labor costs overseas. Suppose that producing intermediate goods domestically costs $1.8 million in labor but that this cost is reduced to $1.3 million at an offshore plant. For simplicity’s sake, we will assume that the $500,000 in lower expenses boosts profit at the intermediate goods company to $1.7 million.

In the absence of border adjustment, a business would have an incentive to relocate to a country with lower wages even if the corporate tax rate were the same. Such advantages disappear, though, in the face of border adjustment; in the above example, the group would see its after-tax income fall to $3.16 million ([$2 million + $1 million] ×0.8 – [$8 million − $5 million] × 0.2 + $1.7 million × 0.8). Here we are assuming that the corporate tax rate in the foreign country is the same 20%. The after-tax income with border adjustment is less than the $3.36 million the business would have earned had it kept production at home.

Destination-Based Principle

These calculations are premised on the foreign country using the origin-based approach to corporate taxation, rather than the destination-based principle. If the offshore plant, too, is subject to border adjustment, then its sales (exports) would be untaxed and only its purchases (imports) taxed. In such a situation, its after-tax income would rise to $1.96 ($1.7 × 0.8 – [$5 million − $8 million] × 0.2) even with a corporate tax rate of 20%, boosting the income of the group as a whole to $3.76 million.

Should the Trump administration embrace the destination-based approach, therefore, other governments would have an incentive to follow suit. In fact, most proponents of the border adjustment tax in the United States argue that the lack of such a tax puts the country at an unfair disadvantage vis-à-vis markets that have value-added taxes.

I hope these examples will help show that the border adjustment tax is not a protectionist measure. It can be considered part of the Trump administration’s efforts to maintain US competitiveness as the world increasingly turns from origin-based tax systems to destination-based systems.

As the failed Obamacare repeal effort suggests, though, the White House’s ability to push policies through Congress appears dubious. That said, the global trend toward the destination-based tax systems is undeniable, and the introduction of a border adjustment tax will continue to be a topic of political debate in the United States. Japan has a value-added tax in the form of the 8% consumption tax, but its corporate tax has no border adjustments. Tokyo, too, needs to review the current tax system critically, including the possibility of introducing border adjustments to its corporate tax, as the day Washington goes forward with tax reform may not be far off.

Translated from “Kokkyo-chosei-zei, kakkoku zeisei ni eikyo,” Keizai Kyoshitsu, Nihon Keizai Shimbun , March 30, 2017. Courtesy of Nikkei Inc.