- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Dialogue and Collaboration for Sustainable Management: Analysis of the Tokyo Foundation’s Fourth CSR Survey

April 2, 2018

I. About the Tokyo Foundation CSR Survey

A. Design of the Survey

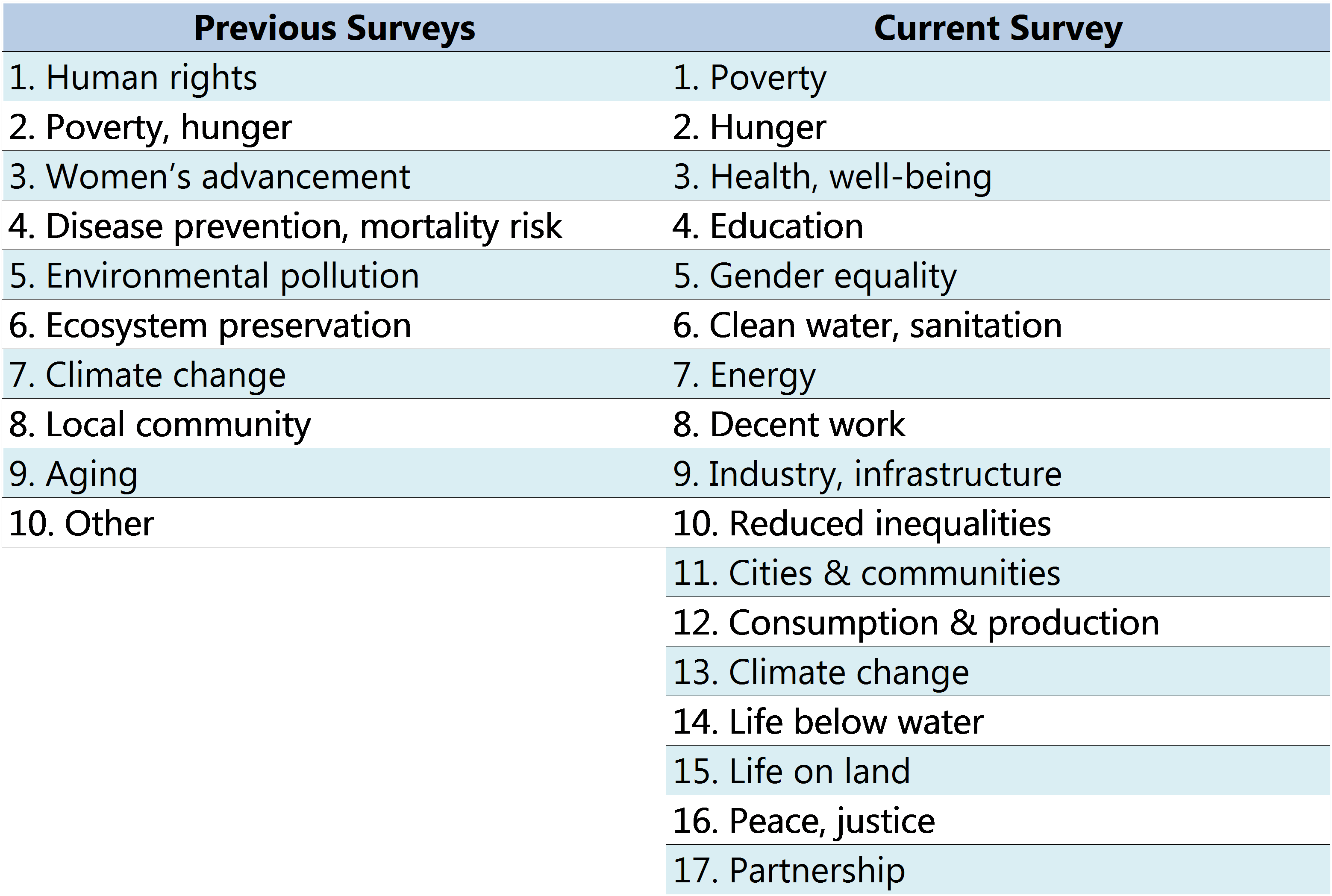

In 2016, the Tokyo Foundation’s CSR Research project team conducted its fourth annual CSR survey. From the beginning, our approach has been to structure the survey around the basic issues facing society, while highlighting engagement with the social sector. Although most surveys on CSR center on corporate activities, we have continued to design ours around social issues in the belief that the resolution of such problems is the heart and soul of CSR. For our fourth and most recent survey, we replaced the 10 issue categories we have used previously with 17 categories aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (Figure 1).

The Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs, were adopted by the UN General Assembly in September 2015 at a meeting attended by more than 150 heads of state. Intended to take up where the Millennium Development Goals left off, the 17 goals, along with 169 targets, are set forth in the document Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development .

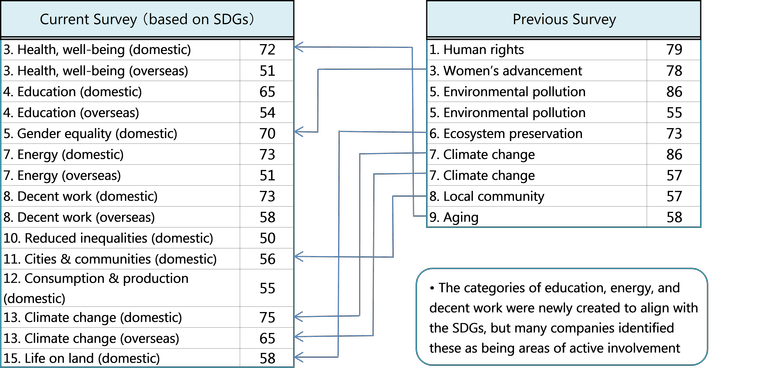

Figure 1. Reclassification of Social Issues

Some critics have compared the SDGs unfavorably to the Millennium Development Goals, complaining, among other things, that they divert the focus from the responsibilities of the industrial world. As we see it, however, the significance of the SDGs lies in the formulation of clear and comprehensive goals and targets oriented to the key challenges humanity must meet in order to pursue continued economic development in a socially and environmentally sustainable manner. Such organizations as Global Compact Network Japan have been working proactively to spread awareness and understanding of the SDGs within Japan. Anticipating a growing role for the 2030 goals as benchmarks for corporate citizenship in Japan, we made the decision to align our classification of social issues with the SDGs.

Among the themes stressed in our previous CSR White Paper (2016) was the need for responsive corporate management that adapts actively and flexibly to ongoing changes in society. The SDGs had just been released, and in anticipation of their impact on CSR, we decided to focus on the ties between business and society. We renewed our call to integrate social initiatives into core business operations, highlighted issues and bottlenecks in Japanese CSR programs, and identified key strategies for overcoming those obstacles, noting that the same strategies were keys to companies’ long-term survival.

In the 2016 White Paper, we drew attention to what we consider to be an important shift in the orientation of CSR: from an inside-out process—in which companies view society through the lens of their own business—to an outside-in process, in which they reexamine their own raison d’etre and capacity to solve social issues from an objective, global perspective. Companies need to get past the notion of “doing what we do best” and begin instead by identifying society’s biggest needs. This will require new skills centered on engagement and integration.

The 2016 CSR White Paper analyzed the problems Japanese companies encounter in pursuing CSR in terms of three basic stages in the CSR process: identifying social issues, internalizing those issues as an organization via CSR programs, and mitigating the problems through concrete action. For companies to effectively address social issues, one step must lead to the next in a smooth process that is integrated with business operations.

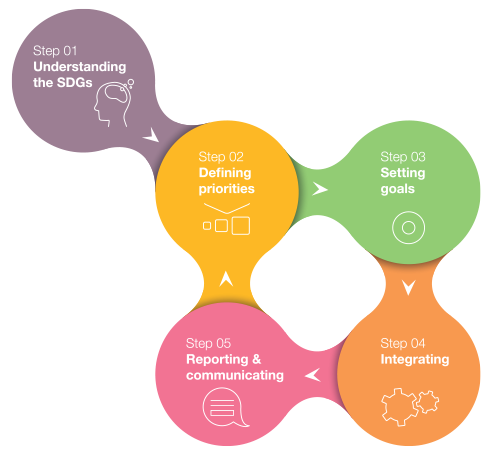

Our three-step process closely mirrors the five steps outlined in the SDG Compass, a set of guidelines for corporate action developed by the Global Reporting Initiative, the UN Global Compact, and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (Figure 2). The main difference between our scheme and the SDG Compass is that the latter perceives the integration of social action into corporate management as a separate step, whereas we believe that the entire CSR process should be integrated into business operations (that is, management). We also feel that stakeholder dialogue and collaboration with the social sector should be pursued throughout the CSR process.

Figure 2. SDG Compass

Such subtle differences notwithstanding, the availability of these systematic guidelines is bound to smooth the way for companies that are not sure how to take action on social issues, and we welcome their publication as a positive outgrowth of the SDGs.

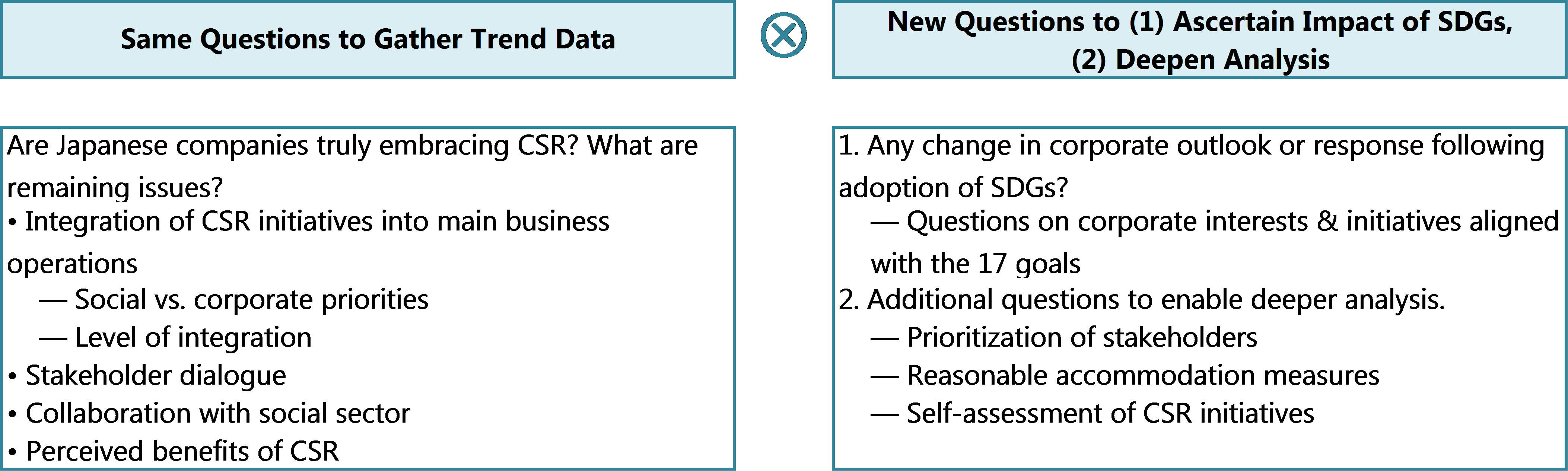

Such, then, were the considerations that influenced the design of our fourth CSR survey. With regard to such factors as stakeholder dialogue, collaboration with the social sector, and perceptions of the benefits of CSR, we repeated questions posed in previous years so as to gather important trend data. We also added some questions under the heading of stakeholder dialogue to facilitate a deeper analysis. In addition, we introduced new questions regarding the impact of the SDGs and reasonable accommodation, in part to assess how nimbly Japanese corporations are responding to society’s changing needs and expectations—in other words, how well they are doing in terms of “building responsive companies”—the theme of our 2015 CSR White Paper.

By preparing a sampling of questions on various topics reflecting the latest CSR issues, we think we have been able to provide a more multifaceted, up-to-date picture that illuminates the maturation of Japanese CSR while highlighting new areas for improvement.

Figure 3. Basic Design of the Latest Survey (2016)

As a result of the changes and additions explained above, the CSR survey has grown longer and more complex. A good number of respondents appear to have found certain questions difficult to answer, particularly those regarding the SDGs, which are still relatively new. In some cases we have refrained from publishing an analysis of the answers to specific questions owing to the small size of the responding sample.

B. Response

1. Surveys Again Returned by About 200 Companies

On September 5, 2016, using publicly available information, the Tokyo Foundation mailed questionnaires to approximately 2,400 companies, targeting corporations listed in the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, leading unlisted companies, and major Japanese affiliates of foreign-based companies. The deadline for submission of completed questionnaires was November 30. We received valid responses by post or email from 197 companies. Of these, 148 (75%) had also responded to the previous year’s survey. Almost 80 companies have participated in all four of our surveys.

There was no indication that the 25% change in the makeup of the sample distorted the results of the survey, discussed at length below. This substantiates our belief that yearly changes in the sample—including the 37% turnover between the 2014 and 2015 surveys—have had no appreciable impact on the outcome of our analyses, and that the results accurately portray the state of CSR among Japan’s major companies.

The number of CSR-related surveys conducted in Japan has risen of late, particularly in the wake of the publication of the SDGs in late 2015. Cognizant of the time and effort that goes into completing these questionnaires, we would like to extend our sincerest thanks to all those who participated in the Tokyo Foundation’s CSR survey.

2. Profile of Responding Companies

Most of the survey responses came from companies to which we had mailed questionnaires. In 2016, as in the past, our sample was not random but slanted toward listed companies. Consequently, most of the respondents were large corporations. However, a significant number of smaller companies submitted completed questionnaires on their own initiative via the Tokyo Foundation website. Judging from their responses, many of these companies have developed CSR programs as impressive as those of much larger corporations, despite the limited human and financial resources at their disposal. Of course, in today’s world, expectations for responsible corporate behavior must apply across the board, regardless of company size. Nonetheless, we feel it is appropriate to acknowledge the efforts of these forward-looking small and medium-sized enterprises and their contribution to the resolution of important social issues.

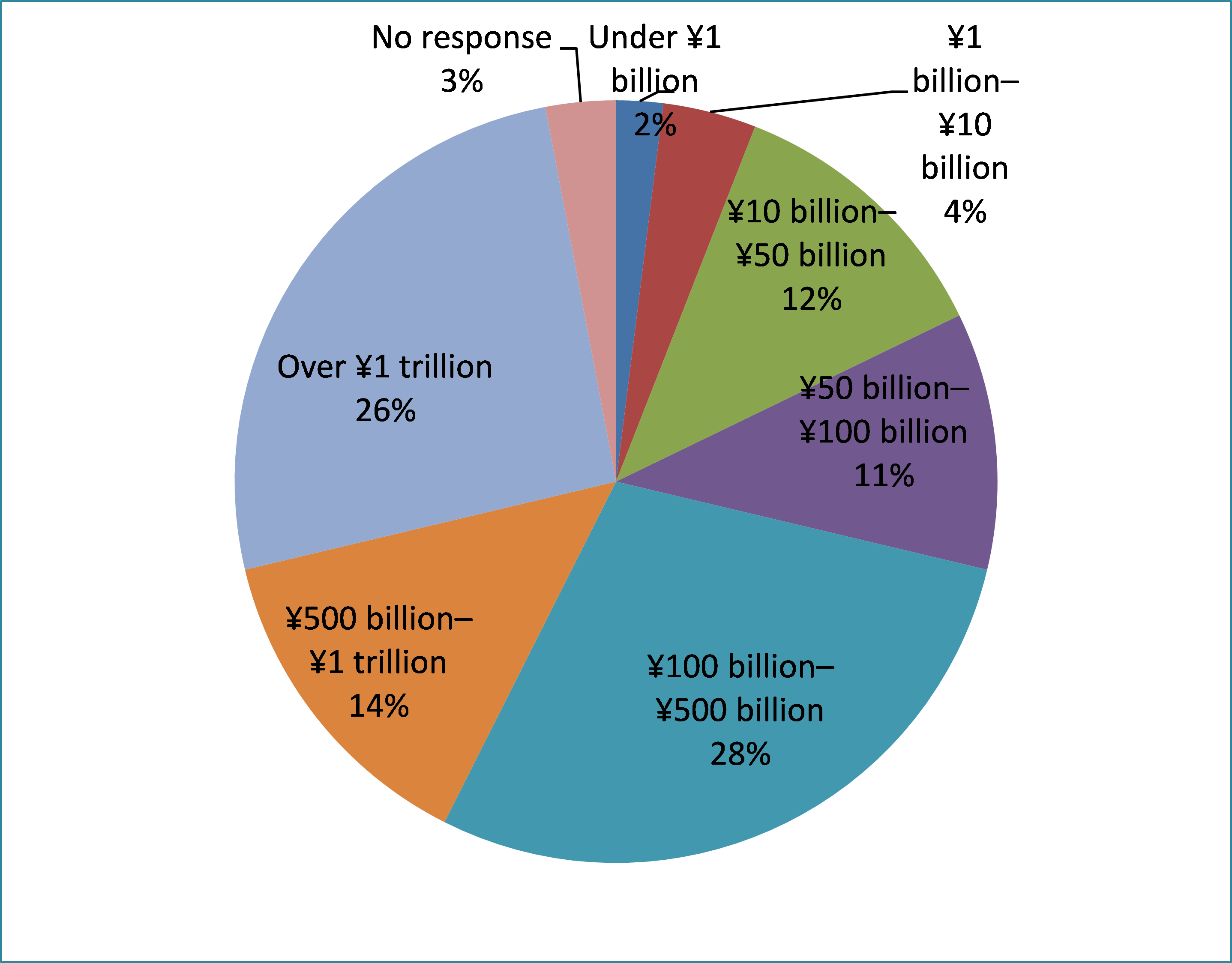

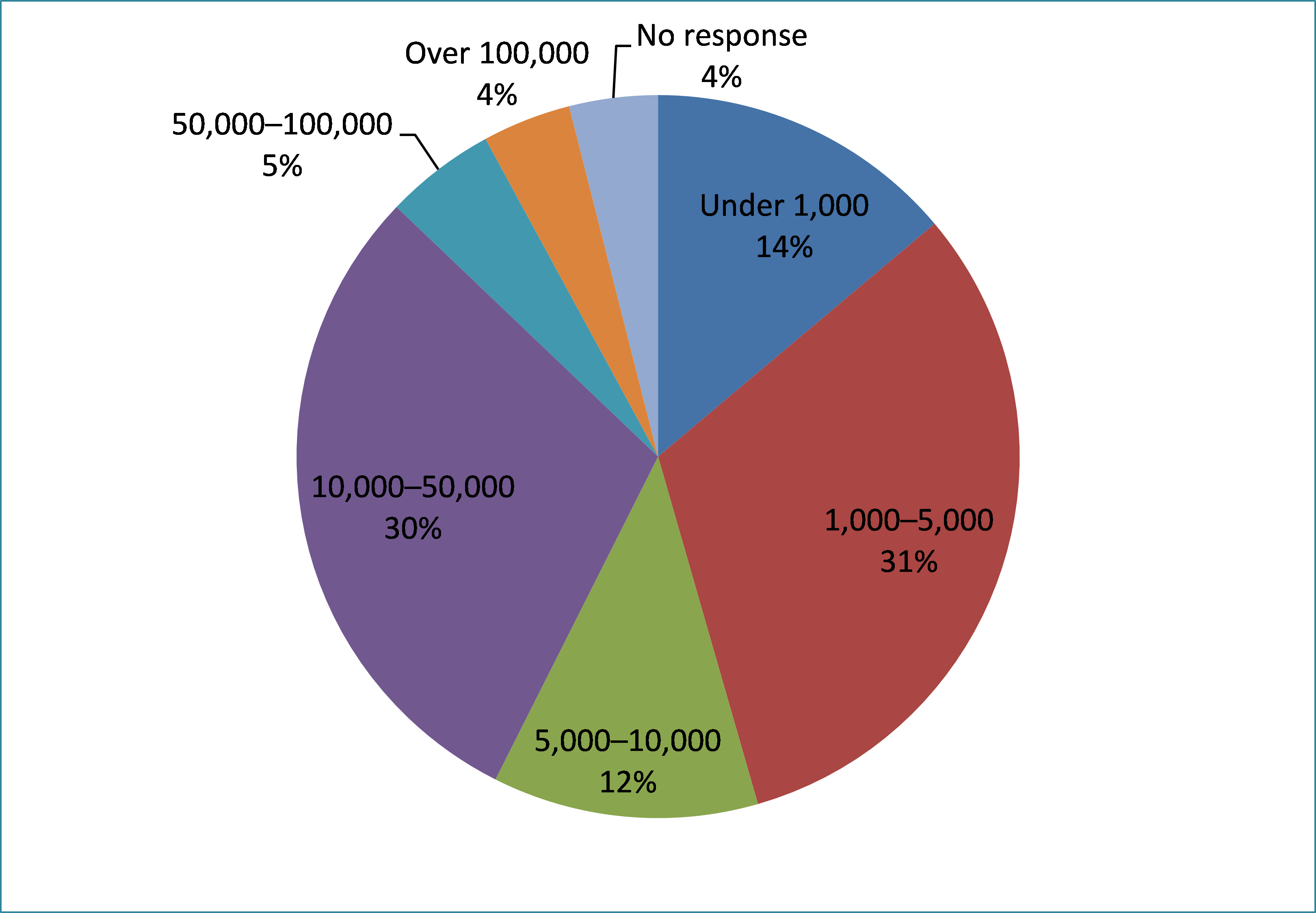

In terms of income, the biggest share of the sample consisted of companies with annual sales between 100 billion and 500 billion yen (Figure 4). In terms of workforce, those with 1,000 to 5,000 employees made up the largest group (Figure 5). This breakdown has not changed appreciably in recent years. It is worth noting, however, that the sample of the Tokyo Foundation CSR survey appears to span a wider size range than the samples of other surveys on the subject conducted in Japan. We consider this one of the distinguishing features of our own survey.

Figure 4. Breakdown of Responding Companies by Sales

Figure 5. Breakdown of Responding Companies by Number of Employees

II. Survey Findings

A. Response to SDGs

As noted above, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, published in 2015, were expected to have a major impact on companies’ CSR programs by defining the basic challenges facing human society. With this in mind, we posed a number of questions pertaining to the SDGs.

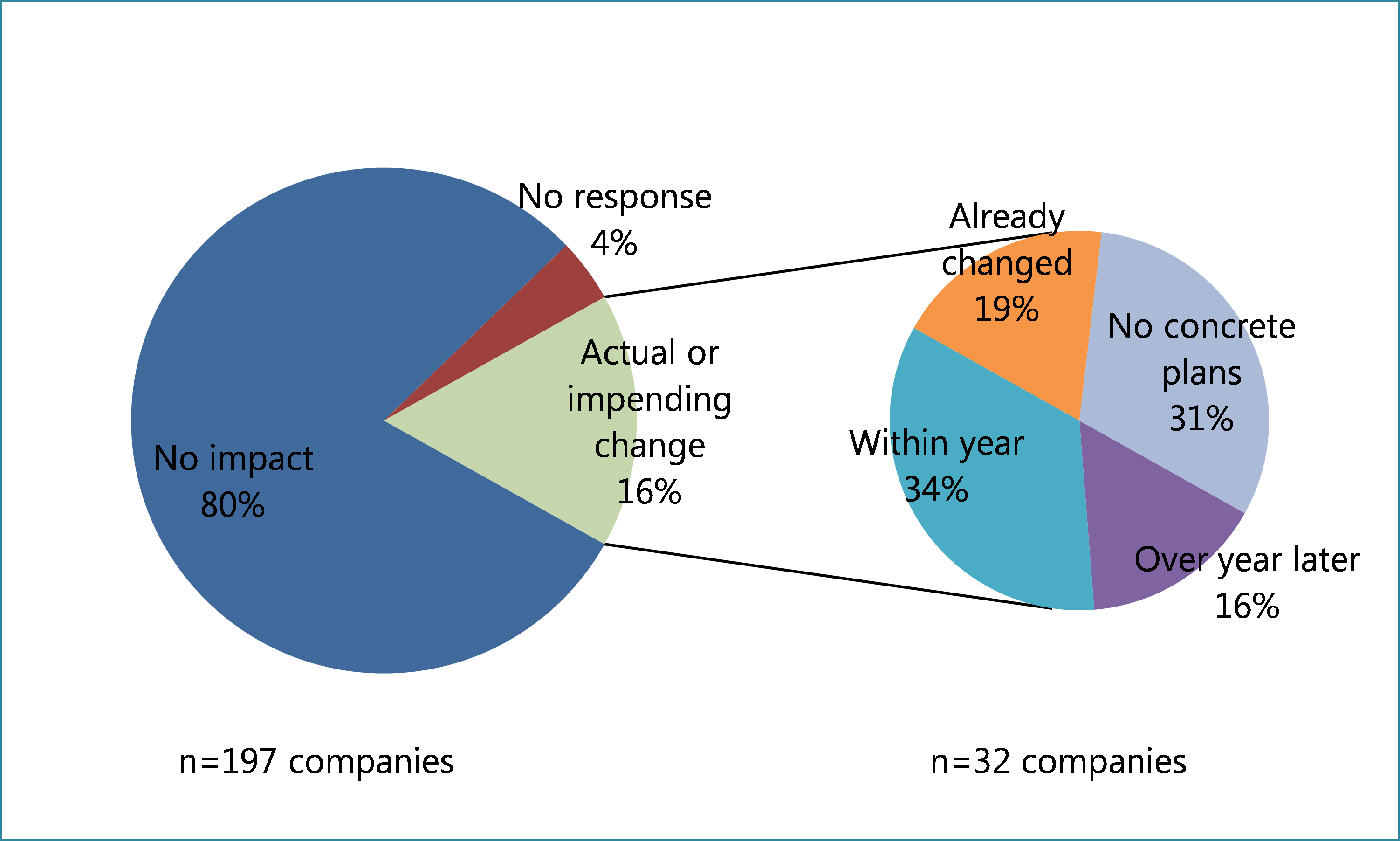

First, we attempted to gauge the effect of the SDGs on CSR programs by asking about their impact on companies’ identification and assessment of material issues—in other words, their own prioritization of various social issues from the standpoint of responsible and sustainable business management. Approximately 80% of respondents replied that the SDGs have had no impact in this respect. Of the 16% that indicated a change (actual or impending), many were vague about when it would occur (Figure 6). These results suggest that the impact of the SDGs has thus far been quite limited.

Figure 6. Changes in Identification of Material Issues in Response to SDGs

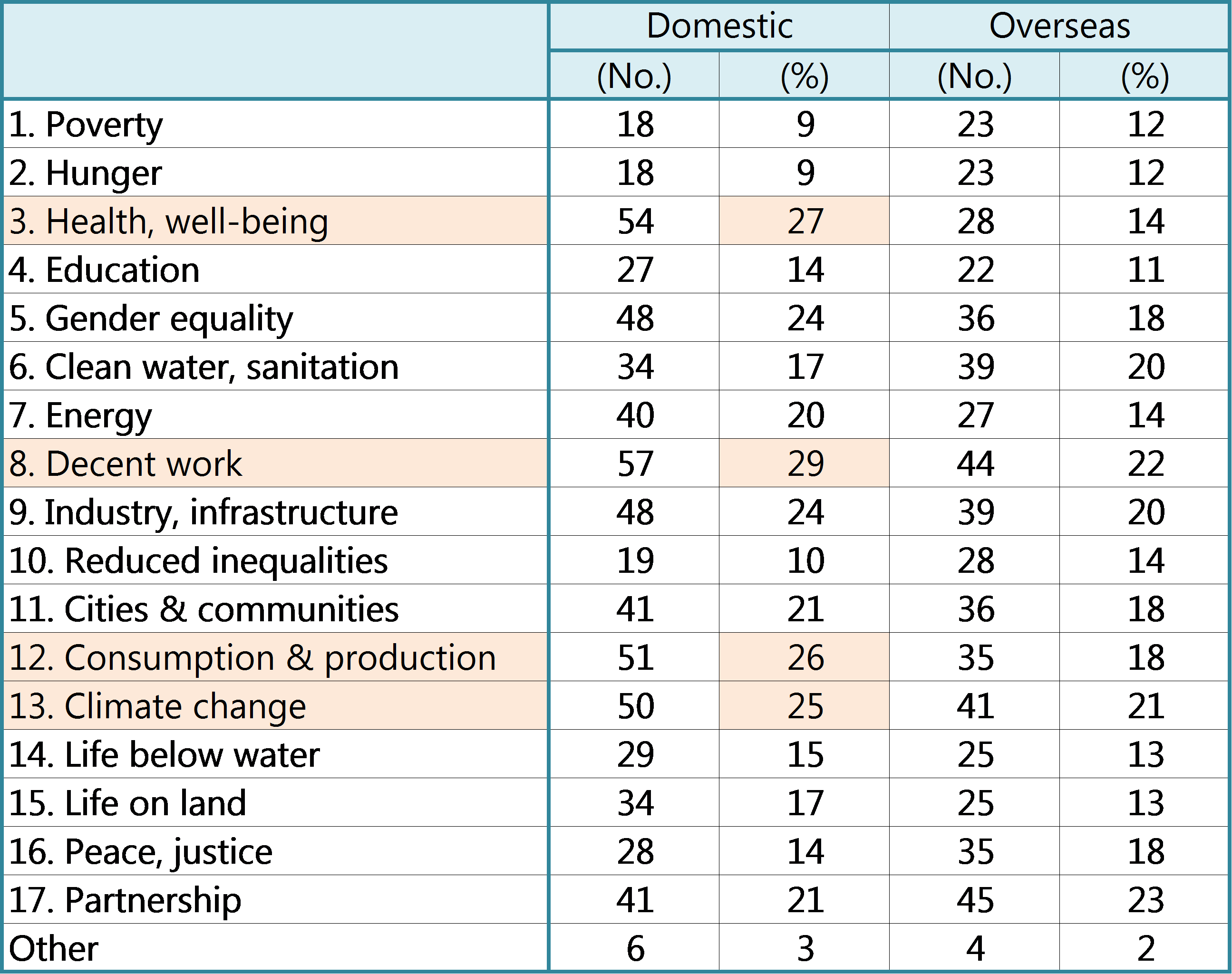

This impression is confirmed by the answers to a question that sought to establish whether the publication of the SDGs had resulted in a “new recognition” of specific issues, as they pertain to Japan and countries overseas (Figure 7). Our purpose was to identify issues that the SDGs had brought to the attention of Japanese companies for the first time. The four issues identified by more than 25% of respondents were (1) health and well-being; (2) decent work; (3) consumption and production; and (4) climate change (all at the domestic level). Inasmuch as all of these are social issues that Japanese companies have identified in previous surveys as major agenda items for CSR, it seems likely that respondents misunderstood the intent of the question.

Figure 7. New Recognition of Social Issues as a Result of SDGs

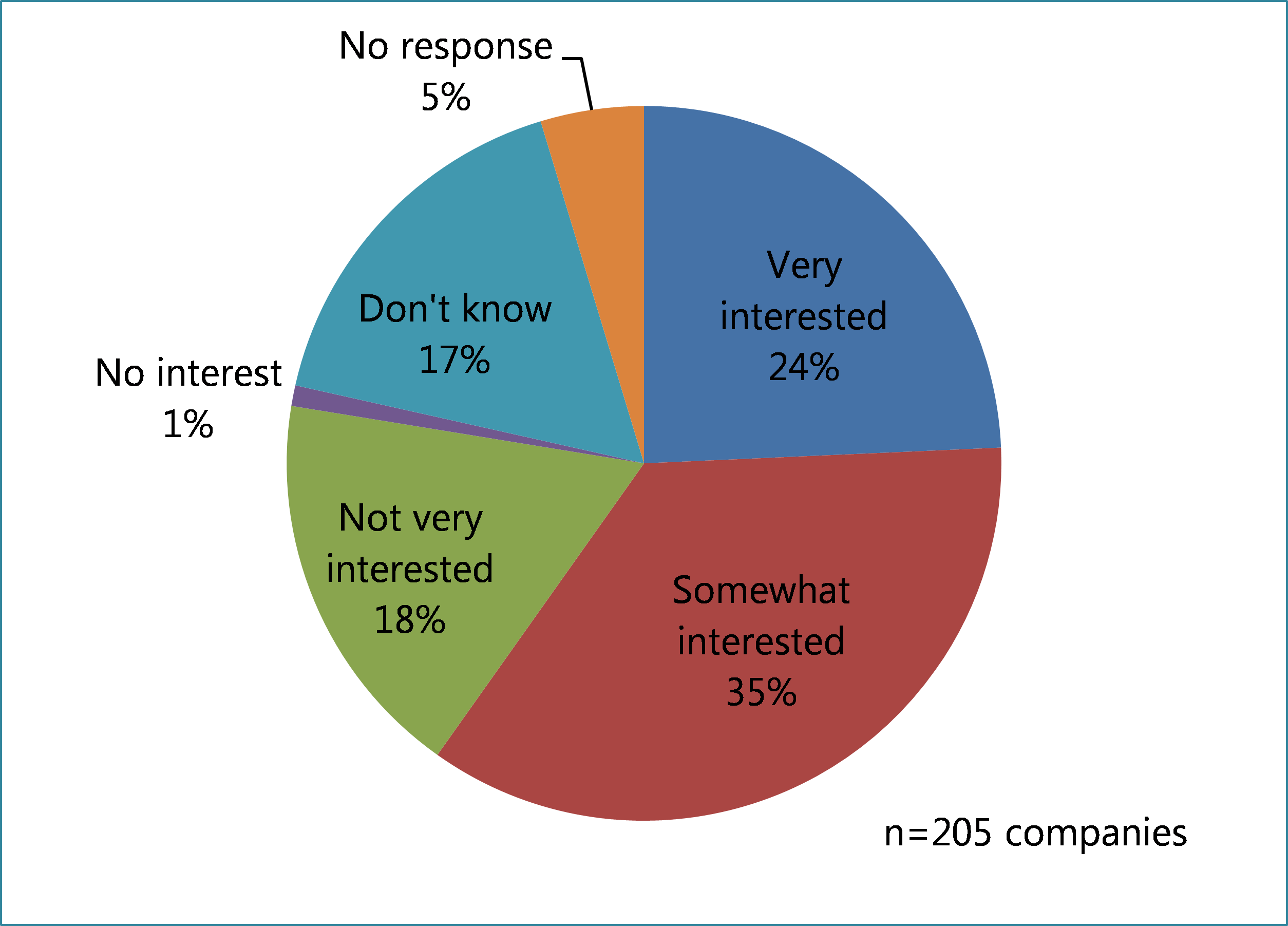

These survey results lead us to the conclusion that the SDGs have had at best a limited impact on the design of CSR programs in Japan. Yet in the previous (2015) survey, a substantial majority of respondents declared themselves either very or somewhat interested in the SDGs (Figure 8). In other words, while Japanese businesses are neither unaware of nor indifferent to the SDGs, they have not felt impelled to revise their CSR priorities to reflect the exact content or wording of the SDGs.

The main reason for this, judging from the results of the latest survey and of that conducted a year earlier, is that most Japanese companies were already familiar with most of the social issues underlying the SDGs and had previously assessed their materiality vis-a-vis their own CSR programs. This would explain why so few have not revised their priorities to reflect the 17 SDGs, contrary to our expectations.

Figure 8. Level of Interest in SDGs (from previous survey)

Figure 9 displays the leading issue categories in the last two Tokyo Foundation surveys—that is, the basic issues in which the largest percentage of companies were involved, according to the survey results. Arrows connect the headings that remained basically unchanged: women’s advancement, ecosystem preservation, climate change, local community, and aging. Education, energy, and decent work are newly created categories aligned with the SDGs. Even so, many companies identified these as areas of active involvement. This tells us that most of the responding companies had already identified them as material issues and launched initiatives to address them even before the SDGs were published. The results provide confirmation for our hypothesis that the SDGs did not propel changes in companies’ CSR priorities because most Japanese businesses were already aware of the underlying issues and taking steps to address them.

On the other hand, certain challenges continue to fall under the radar. Some may argue that this is inevitable, that companies need to prioritize rather than attempt to tackle every issue. Be that as it may, it is hard to accept such a low rate of action on poverty and hunger in Japan, given the attention focused on the problems—particularly child poverty—in recent years. According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, in 2015, almost 14% of Japanese children were living in poverty. Surely this is not something we can allow to continue.

Figure 9. Most Commonly Addressed Issues (%)

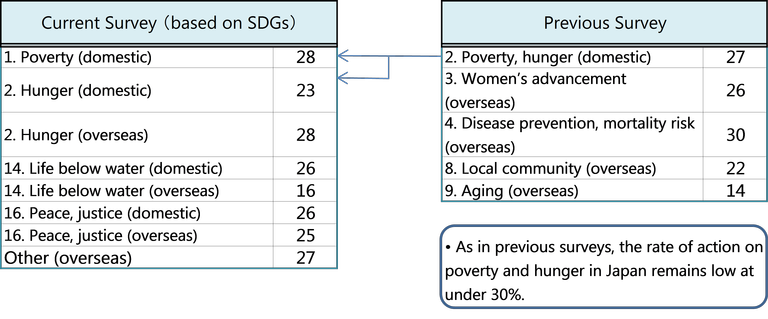

Figure 10. Least Commonly Addressed Issues (%)

Another issue that has received inadequate attention at the corporate level is stewardship of the oceans and marine resources. Japan is an island nation that has depended on and benefited from the ocean’s bounty throughout its history. Problems affecting the oceans should be a matter of the utmost concern to Japan, particularly now that they have been articulated in the SDGs. Yet relatively few companies have taken action on these challenges either domestically or overseas.

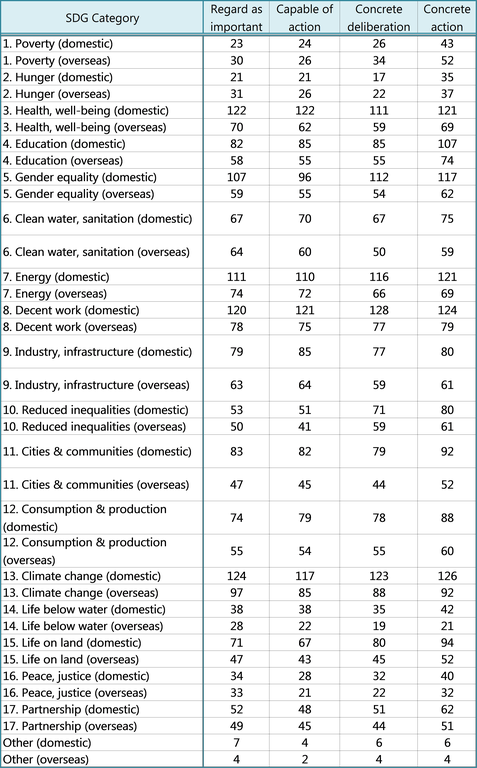

Figure 11 highlights a more structural problem, namely, the tendency of Japanese companies to take action on issues without adequate deliberation and prioritization based on their own capabilities. This tendency to proceed straight to the action phase of CSR explains why, in many cases, the percentage of companies engaged in action on a particular issue is substantially higher than the percentage that regard the issue as important. We had wondered if the publication of the SDGs would facilitate a more systematic, deliberative CSR process, but no change was evident.

Figure 11. Interest and Involvement in (SDG) Issues in Japan and Overseas

(Number of companies)

To repeat, then, the impact of the SDGs on Japanese CSR programs—a major focus of the 2016 survey—was modest at best, judging from the small percentage of companies that altered their materiality assessments in response to the SDGs. However, as the answers to other questions indicate, one important reason for this is that the majority of companies were already tackling, in one way or another, many of the issues that the SDGs target.

At the same time, the response to certain challenges, such as poverty and stewardship of the oceans, remains lackluster, even now that the SDGs have brought them into sharper focus. While our responding companies seem to be keeping up the good work on the issues that have engaged their attention for some time, the survey results suggest that they are reluctant to broaden their focus to include new issues highlighted by the SDGs. This seems like an accurate characterization of the state of CSR in Japan today.

B. Stakeholder Dialogue

As noted in the 2016 CSR White Paper, stakeholder dialogue correlates strongly with awareness of social issues and commitment to addressing them. There is little doubt that stakeholder dialogue is a key tool for jump-starting and advancing CSR. Let us take some time, then, to examine trends in stakeholder dialogue.

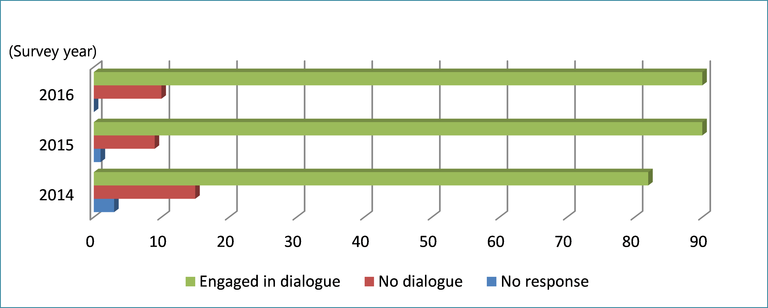

As Figure 12 indicates, the percentage of companies engaged in some form of stakeholder dialogue has plateaued at around 90%. Given that almost all of the very small businesses (around 10 employees) surveyed responded in the negative to this question, it seems fair to conclude that close to 100% of listed companies are currently engaged in stakeholder dialogue of some sort. From our previous survey, we determined that companies that engage in stakeholder dialogue are much more likely to be tackling social issues than those that do not. Taken together, these results tell us that Japanese businesses are on the right track.

Figure 12. Percentage of Companies Engaged in Stakeholder Dialogue (2014—16)

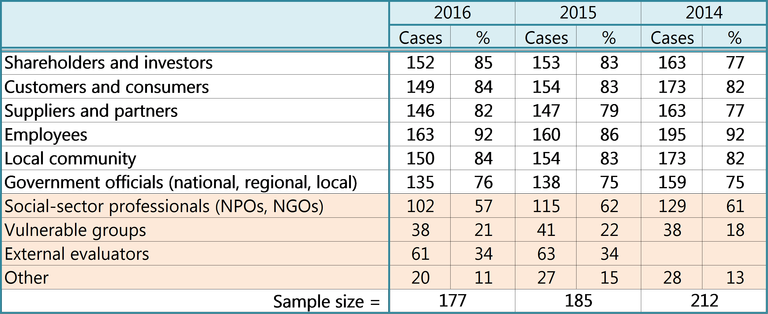

Figure 13. Percentage of Companies Engaged in Dialogue by Stakeholder Group

Which stakeholder groups do Japanese companies favor as dialogue partners? Figure 13 displays the percentage of respondents engaged in dialogue with each stakeholder group over the past three years. While there has been some fluctuation, the results are quite consistent overall.

Of the groups listed, five were identified by more than 80% of responding companies as dialogue partners: shareholders and investors, customers and consumers, employees, the local community, and suppliers and partners. A much smaller percentage of respondents identified vulnerable groups and external evaluators as dialogue partners. Social-sector professionals (NPOs, NGOs) fell somewhere in between. More than half of respondents identify this group as a dialogue partner. Still, the ratio fell in the latest survey, dropping below 60%.

Only about 20% of responding companies are engaged in dialogue with vulnerable groups, and the ratio has not changed significantly over the past three years. This is an area in which Japanese companies are weak. As discussed elsewhere in this year’s CSR White Paper, providing adequate employment opportunities for people with disabilities and other vulnerable groups should be a top agenda item for Japanese companies, both from the standpoint of compliance with the Act for Eliminating Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities and from the perspective of generating economic and social value by encouraging those with disabilities to join the workforce. Active dialogue with such underrepresented groups is a crucial step in that direction.

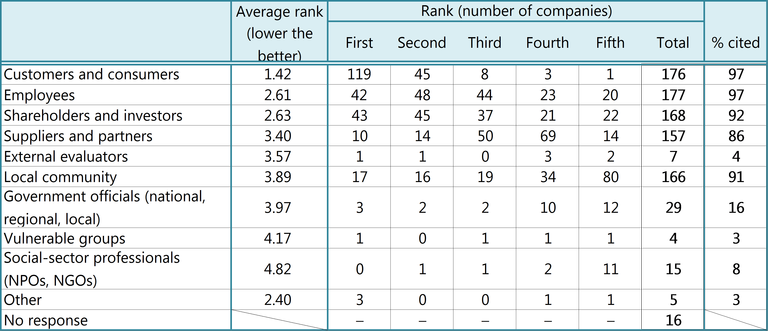

In the most recent survey we added a new question in which respondents were asked to rank the five stakeholders they consider most important as partners in dialogue (Figure 14). We hoped that the results would add a significant new dimension to our analysis of stakeholder dialogue, and we were not disappointed.

Figure 14. Companies’ Priority Rankings of Dialogue Partners

The five top-ranked stakeholders, according to our analysis, were (1) customers and consumers, (2) employees, (3) shareholders and investors, (4) suppliers and business partners, and (5) the local community. Our ranking takes into account the number of respondents identifying each group as well as the average score. Thus, although external evaluators came in slightly higher than the local community in average ranking, only seven respondents placed external evaluators among the top five; accordingly, greater weight was given to rankings for the local community.

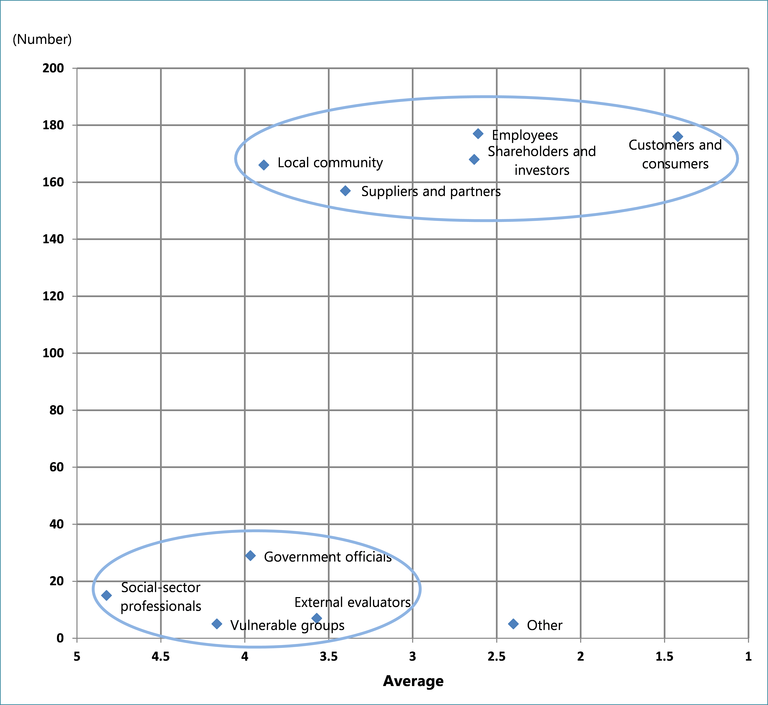

Figure 15 uses a scatter diagram to plot average ranking against frequency of identification. From this chart we can grasp at a glance the relative importance of various stakeholders in the eyes of Japanese companies.

Figure 15. Identification and Ranking of Stakeholder Groups as Dialogue Partners (scatter plot)

From Figure 15, it is immediately apparent that most companies place low priority on dialogue with vulnerable groups and representatives of the social sector (NPOs and NGOs). In other words, the reason so few Japanese companies engage these stakeholders in dialogue is that they consider them relatively unimportant and therefore do not seek them out. This suggests that Japanese companies may not be quite as proactive about stakeholder dialogue as Figure 12 alone might lead one to believe.

Given the important role stakeholder dialogue can play as a driver of CSR, the current bias toward dialogue with certain stakeholder groups at the expense of others cannot be considered healthy.

Of course, many companies find it more challenging to engage with vulnerable groups and NGOs than with investors, customers, or employees. They may lack information about and contacts with such external stakeholders. Even so, the dialogue gap revealed by our latest survey is too extreme to rationalize. Addressing this inequality would appear to a crucial task for Japanese companies going forward.

C. Collaboration with the Social Sector

The special organizational strengths of social-sector groups, such as nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations, have been much in the spotlight in recent years. Japanese businesses have been urged to partner with the social sector to take advantage of its unique ability to mobilize citizens and tap into their resources. Yet, as we have seen, our respondents place relatively low priority on dialogue with representatives of the social sector, although more than 60% are currently engaged in it. To focus renewed attention on this problem, we have chosen collaboration with the social sector as a major theme of this year’s CSR White Paper.

Although respondents were asked about their collaboration with the social sector in previous surveys, at the time we compiled the last CSR White Paper, we had not yet gathered enough data to identify a clear trend. Having asked the same question for a third year, we are now able to attempt a more meaningful analysis of the results.

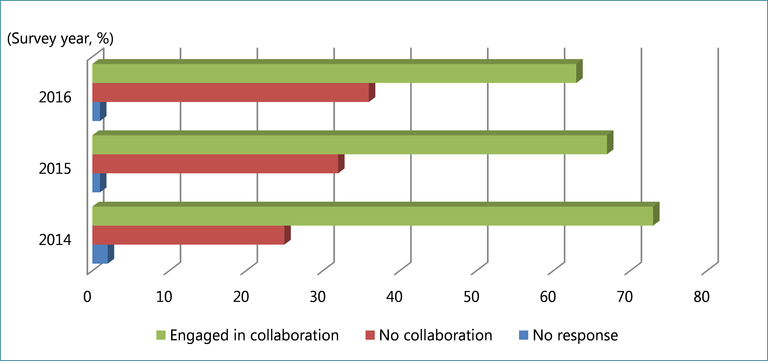

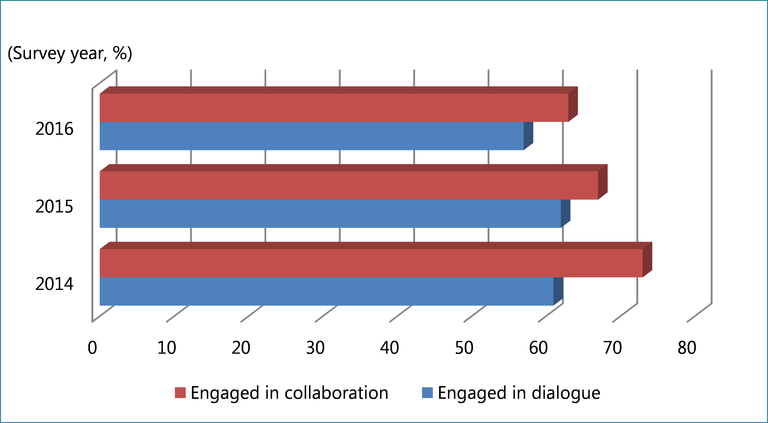

In the most recent survey, 63% of responding companies indicated that they were collaborating with the social sector—the lowest rate recorded thus far. As Figure 16 illustrates, the percentage of respondents answering in the affirmative on this question has declined continuously since 2014, while the percentage of negative responses has risen. This year’s results leave little doubt that collaboration with the social sector is on the decline.

Juxtaposing the rates of collaboration with the figures for dialogue with the social sector throws the three-year trend into higher relief. Figure 17 shows that dialogue and collaboration have both fallen since the 2014 survey. Interaction between the corporate and social sectors appears to be on the wane.

Figure 16. Percentage of Companies Engaged in Collaboration with the Social Sector (2014—16)

Figure 17. Trends in Dialogue and Collaboration with the Social Sector

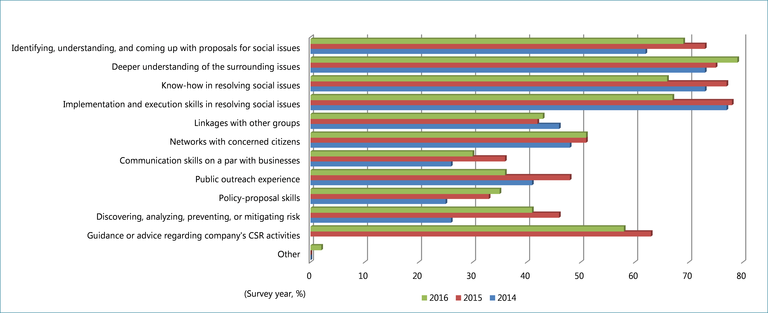

To understand the reasons for this, it might help to know what Japanese companies that do engage in collaboration with the social sector expect to gain. The responses to this question for 2014—16 are tallied in Figure 18. In the 2016 survey, the two benefits most frequently identified were a “deeper understanding of the surrounding issues” and help in “identifying, understanding, and coming up with proposals for social issues.” These benefits pertain to the preparatory stages of the CSR process: identifying challenges and internalizing them as an organization (or Step 1 and Step 2 in the SDG Compass).

The other two most frequent responses were “implementation and execution skills in resolving social issues” and “know-how in resolving social issues.” These are capabilities that apply primarily to the process of internalizing a challenge and initiating actions to address it.

On the other hand, Japanese companies seem less enthusiastic about the social sector’s potential contribution at the execution and evaluation stages. For example, they have low expectations for taking advantage of organizations’ linkages with other groups, networks with concerned citizens, public outreach experience, and policy-proposal skills—all special strengths of the social sector.

Figure 18. What Benefits Do You Expect from Collaboration with the Social Sector? (2014—16)

It has been roughly 15 years since the emergence of CSR as a watchword in Japan. During that time, Japanese businesses have learned a great deal about CSR and how best to pursue it. At the same time, there are signs that they have more or less established their priorities when it comes to tackling social issues, as noted above. Under the circumstances, Japanese companies may well be better equipped than previously to navigate the early stages of the CSR process (identification and internalization) by themselves. This does not mean that they have no need of outside input. But it may well be that they are less conscious of that need. This would explain why they place less value on the contribution of the social sector.

The general trend, as shown in Figure 18, is a decline in expectations, corroborating our hypothesis that the decline in collaboration with the social sector stems largely from the progress Japanese companies have made in establishing their CSR priorities and designing programs around those priorities.

A notable exception to this trend is the increase in the percentage of respondents identifying “deeper understanding of the surrounding issues” as an expected benefit. How can we account for this anomaly? The results of the latest survey offer no clear explanation. This may simply be the default response, reflecting the assumption that the social sector, by virtue of its closeness to social issues, has a deeper understanding of them than the business sector does. But is the growing emphasis on this contribution from the social sector a healthy sign of companies’ desire to gain a deeper understanding of social issues or an unhealthy sign of their inclination to restrict the social sector’s involvement to the first stage of the CSR process? That is for the reader to decide. But given the overall decline in collaboration with the social sector, the latter explanation seems the more likely one.

How can we open the way for more meaningful collaboration between business and the social sectors? This is a topic we will explore in future surveys.

D. Reasonable Accommodation

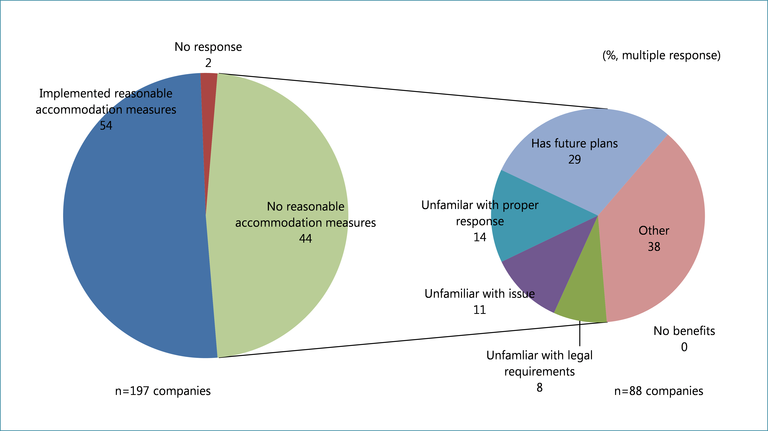

As noted above, providing reasonable accommodation for the disabled is a key challenge facing Japanese industry. With this in mind, we decided to make reasonable accommodation a new focus of this year’s questionnaire. Our survey found that a majority of companies have already taken steps in this area.

The Act for Eliminating Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities came into force in April 2016, just a few months before the Tokyo Foundation mailed out its questionnaires. The fact that more than half of companies responded in the affirmative to this question underscores the oft-noted Japanese emphasis on compliance with “hard law,” as opposed to nonbinding “soft law.” The immediate effect of the new law contrasts sharply with the low impact of the SDGs on companies’ CSR priorities.

Figure 19. Have You Taken Steps to Provide Reasonable Accommodation for Persons with Disabilities? If Not, Why Not?

In recent years, a number of researchers have highlighted the role of “soft law” in establishing and spreading norms for CSR management, citing the impact of such international standards as ISO 26000. We will be watching closely to see whether the SDGs can play a comparable role in the Japanese business community.

E. Governance and CSR Investment (trend data)

The Tokyo Foundation’s annual CSR survey features both new questions reflecting that year’s special topics and a set of core questions that we keep unchanged in order to gather trend data on key CSR factors and indicators. In the following, we use data from such questions to explore trends in corporate governance and CSR management.

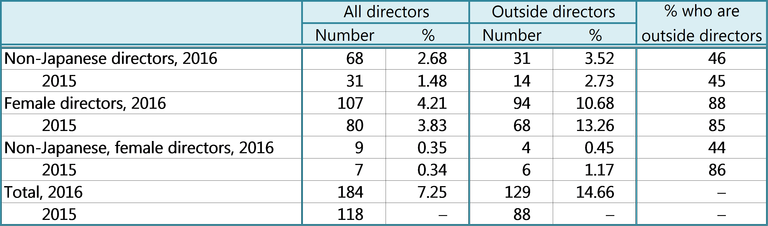

One area we looked at this year was the composition of the board of directors. With the adoption of the Japanese Corporate Governance Code and recent revisions in the Companies Act, corporations have been under pressure to appoint more outside directors. We were interested to see whether the appointment of outside directors would result in greater board diversity with respect to professional background, nationality, and gender.

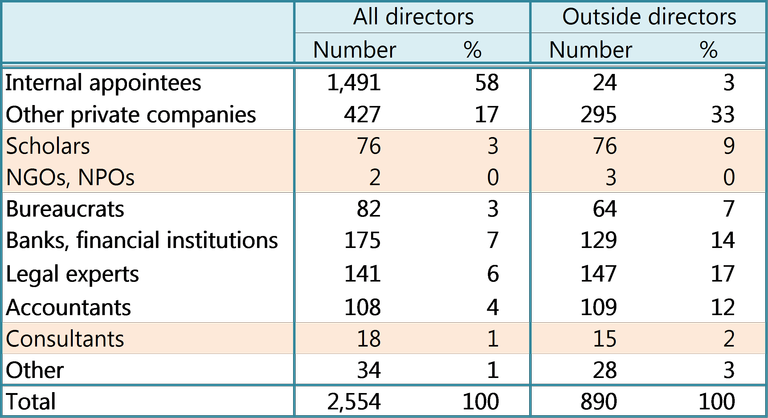

In this latest survey, outside directors accounted for 890 out of 2,554 board members, or 35%. Figure 20 breaks these totals down by directors’ background. (Due to respondent error, the number of outside directors in some cases exceeded the total number of directors.)

Figure 20. Board Members by Professional Background

Figure 21. Non-Japanese and Female Directors

Notwithstanding the rise of outside directors, internal appointees still dominate Japan’s corporate boards, accounting for about 60% of the responding companies’ directors. Japanese companies’ persistent tendency to promote from within has its advantages in terms of guaranteeing continuity and stability and rewarding talented and hardworking employees. But it also tends to foster an insular corporate culture unconducive to open innovation.

Among outside directors, the largest subgroup—295—consisted of former executives at other private companies, including companies in the same corporate group. No doubt such appointees are valued for their experience in business management. In second place were members of the legal profession, accounting for 147 of outside directors. Many of these were doubtless tapped to serve as external auditors.

Much rarer is the appointment of consultants, scholars, and especially professionals from the nonprofit sector—those most apt to cast an outsider’s critical eye on a company’s management. This is not to say that others cannot provide criticism, but advice given from the standpoint of a nonprofit organization is bound to differ substantially in focus and thrust from that offered by a business executive.

Next, let us look at the number of non-Japanese and female directors. As indicated in Figure 21, foreign nationals and women have both made gains, in terms of absolute numbers and as a share of the total. When it comes to nationality and gender, boardroom diversity seems to have improved slightly. The number of non-Japanese and female outside directors has increased as well, but because total number of outside directors has climbed so sharply, the share of outside directorships held by women has not grown since the last survey.

We were struck above all by how many of the non-Japanese and women directors were outside appointees—46% and 88%, respectively. In fact, out of 107 women, only 13 were appointed from inside the company. Women promoted from within accounted for a mere 0.5% of the total membership of responding companies’ boards of directors.

Before women employees can be appointed as directors, they must first hold key management posts. The government wants women to occupy at least 30% of management positions in Japanese businesses by the year 2020. But as long as Japanese companies adhere to current personnel practices, it could be many more years before a substantial number of female employees make it to the top of the corporate ladder.

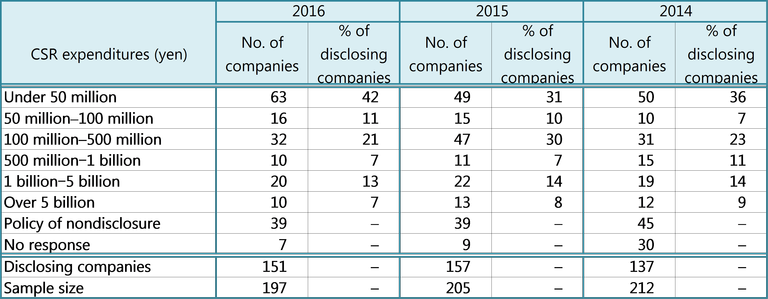

The next topic under this heading is CSR expenditures. Figure 22 tabulates the number of responding companies in each CSR budget bracket and their share of the total over the past three surveys. One change is a drop in the number of respondents who skipped the question entirely. In our second survey, conducted in 2014, a full 14% of the respondents left this section blank. While many companies have worked to improve transparency in keeping with international standards, there has been some lingering resistance to disclosure of CSR spending, a key indicator of the scale of a company’s CSR commitment. Gradually, however, this resistance is dwindling. In the fourth and most recent survey (2016), only 4% of respondents left the budget question blank. Moreover, the rate of disclosure has risen from 64.6% in 2014 to 76.6% in 2016. We applaud this trend toward greater transparency, also apparent in the publication of CSR reports.

Figure 22. Spending to Address Social Issues

Another trend worth noting is the decline in both the number and percentage of companies in the three biggest spending brackets (500 million yen and up) and an increase (between 2014 and 2016) in the number of those spending less than 50 million yen. In the intermediate brackets (budgets between 50 million and 500 million yen), there is no clear trend.

Since the survey asks respondents only to identify their spending bracket, it is impossible to calculate total expenditures even by those companies providing spending information. Moreover, with a substantial number of respondents declining to identify their bracket, we cannot be certain whether overall expenditures have declined. However, the information available to us does suggest a drop in CSR spending. This might simply reflect a more focused and efficient use of financial resources as companies accumulate experience and know-how. On the other hand, it might mean that companies are cutting back on their CSR programs. One of the tasks for our next survey will be to shed further light on spending trends and the forces driving them.

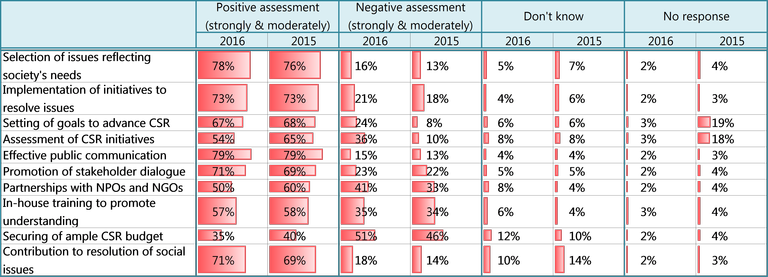

The last topic in our analysis is self-assessment with regard to CSR. How do Japanese companies evaluate their own CSR programs, and what do they regard as their major shortcomings? The answers to these questions in the most recent survey and the previous one are tabulated in Figure 23.

Figure 23. Self-Assessment of CSR

One significant change was a decline in positive responses vis-a-vis “assessment of CSR initiatives” and “partnerships with NPOs and NGOs.” In both cases, the percentage of strongly and moderately positive self-assessments dropped by about 10 points. Also noteworthy was the sharp increase in negative self-assessments on “setting of goals to advance CSR” and “assessment of CSR initiatives.” Negative assessments relative to “partnerships with NPOs and NGOs” are also on the rise. On the whole, respondents appeared slightly more critical of their own efforts this time than in the previous survey.

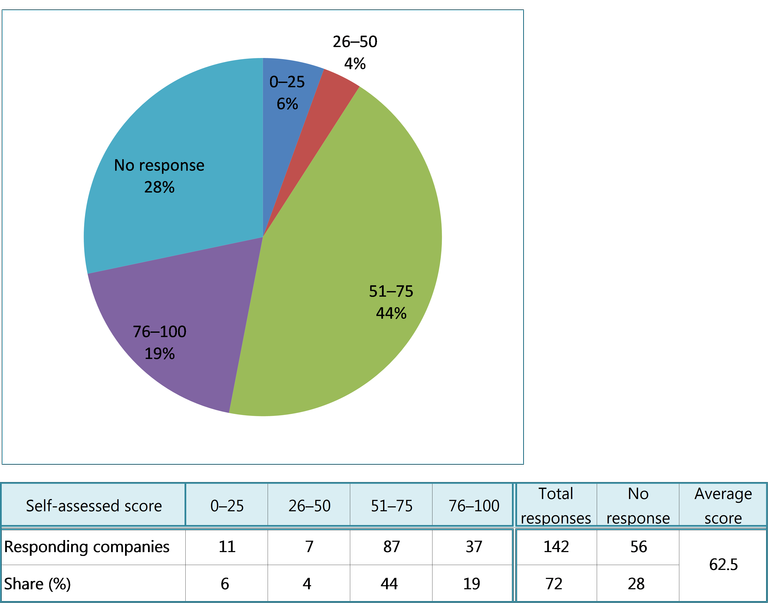

In this survey, we added a question in which respondents were asked to rate their companies’ CSR efforts on a 100-point scale. The mean score among those who answered the question was 62.5.

Figure 24 charts the distribution of self-assessed CSR scores. Scores in the 51—75 point range accounted for 44%, the largest share. Two respondents gave their companies 100 points. Those two companies differ markedly in terms of their line of business, size, and CSR budget. What they have in common is a very active commitment to dialogue and collaboration with stakeholders. This interaction with people and organizations outside the company may be what fuels their pride in their own CSR programs.

Figure 24. Distribution of Self-Assessed CSR Scores (100-point scale)

III. Conclusions

What conclusions can we draw from the results discussed above, particularly in relation to this year’s thematic focus: dialogue and collaboration?

First, as we have seen, the survey results indicate that the impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on Japanese companies has thus far been limited. About 80% of respondents said that they did not alter their CSR priorities in response to the SDGs, and the goals do not appear to have brought new social issues to the attention of many companies. However, this does not mean that the significance of the SDGs has been lost on Japanese industry. The results of the previous survey showed a high level of interest in the SDGs. But because the issues targeted by the SDGs were not new to Japanese companies, they did not lead to a significant change in CSR priorities. Viewed charitably, this can be taken as a testament to the maturity of Japanese CSR. Viewed critically, it bespeaks a growing rigidity.

Because Japanese companies emphasize yearly progress toward CSR targets, there is a tendency to focus on the same issues year after year. Our survey results show very little change in emphasis. As we have noted time and again, a broader perspective is the most fundamental cure for what ails Japanese CSR.

Second, while the percentage of responding companies engaged in stakeholder dialogue is quite high, our survey reveals a strong bias in the selection of dialogue partners. Japanese businesses seem wary of the social sector, judging from their level of engagement with NGOs and NPOs. One reason for this may be that they lack sufficient information about such organizations. The foreign companies whose best practices we profiled in the 2015 CSR White Paper were notable for the way they actively researched NPOs and NGOs in order to select appropriate dialogue partners for any given issue. Such companies are not afraid to engage with the social sector. On the other hand, it is natural to shy away from dialogue with an organization one knows nothing about. We recommend that Japanese businesses begin by learning more about the social sector and the organizations that belong to it.

Third, the results of the three last surveys reveal a decline in the rate of collaboration with the social sector. They also indicate that Japanese businesses have lower expectations for such collaboration. The precise reasons for this trend are difficult to pinpoint. Certainly cooperation with nonprofit organizations, whose purpose differs fundamentally from that of profit-seeking businesses, poses challenges. But when it comes to addressing social issues, there are very few corporations that could not benefit from the social sector’s know-how and resources. Japanese companies need to pursue such partnerships affirmatively with the ultimate goal of becoming hubs in a network linking many social-sector organizations.

Fourth, our survey results suggest that Japanese corporations are making satisfactory progress in the area of reasonable accommodation. Other surveys have found Japanese businesses to be relatively conscientious when it comes to compliance with laws and regulations, and this may account for their rapid progress vis-a-vis reasonable accommodation. That is a good place to start. But at some point, providing employment opportunities and accommodations for the disabled—like other aspects of CSR—is likely to take on a strategic dimension transcending mere compliance. Will Japanese companies be able to make the transition? We suggest that now is the time to start thinking outside the box of compliance with the letter of the law.

Finally, let us review the survey’s findings relative to governance and CSR self-assessment. With regard to the former, the results reveal that Japanese businesses have considerable room for improvement when it comes to diversity in the boardroom, and that they are particularly deficient in women directors appointed from within the company. Recently, the Japanese government has set concrete targets for labor reforms facilitating better work-life balance, and it has begun taking steps to encourage women’s active participation in society. This is not just a matter of human rights. With its rapidly aging population, Japan will be hard-pressed to secure an adequate labor supply and sustain economic growth unless it does a better job tapping the potential of women. Under the seniority-based personnel system common in Japanese companies, it will take many years for women to move up the ladder to the boardroom even in the best of circumstances. We will be watching closely for positive change in this area.

In terms of CSR self-assessment, companies seem fairly satisfied with the status quo. Of the 142 companies that scored their own performance, 124, or about 87%, gave themselves at least 50 points. By tracking trends in self-assessment and correlation with other indicators, we hope to provide companies with strategies for improving their scores.

In his book Capitalism at the Crossroads , Cornell University Professor Stuart L. Hart argues that for companies to achieve sustainable growth, they need to deepen their engagement with external stakeholders, including nonprofits, and gain the kind of knowledge and experience that cannot be acquired merely through the pursuit of business in the traditional sense. Seen in this light, dialogue and collaboration are important concepts not only for CSR but also for a company’s basic business strategy. We would like to see more businesses approach the challenge from that perspective.

Once again, we wish to express our deep gratitude to all those who have taken time out from their busy schedules to participate in this survey. Needless to say, this report would not have been possible without their generous cooperation.