A Half-Century of Business Partnerships

Japanese businesses have been forging cross-border partnerships with Taiwanese firms for decades now, though the form these tie-ups take has evolved with the times and the changing needs of both countries. From the mid-1960s through the 1970s, Japanese manufacturers looked to Taiwan as a base for the assembly of manufactured exports. The period spanning the 1980s and the early 1990s saw the rise of cross-border partnerships in third countries. From the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, Japanese corporations began developing stronger complementary relationships with Taiwanese industry as their operations expanded into other Asian countries.

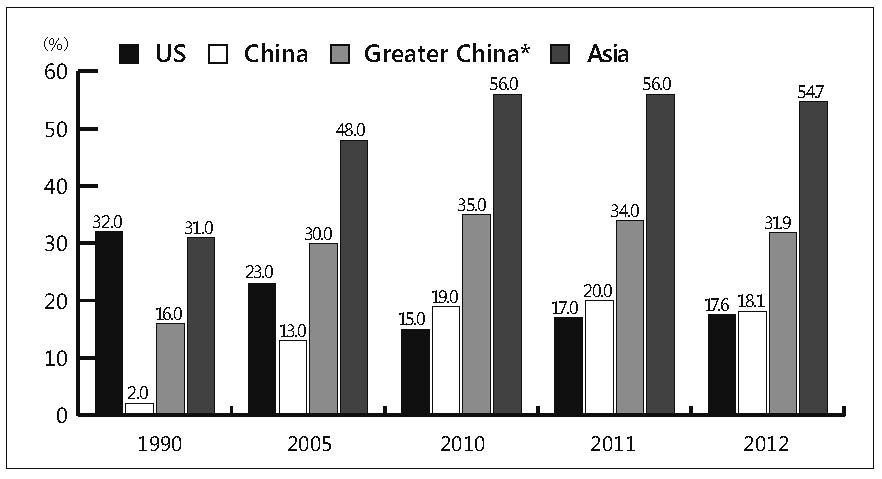

The structure of Japanese trade has changed dramatically since the 1990s, with the focus veering sharply away from the United States and toward Asia. Between 1990 and 2012, the share of Japanese exports bound for the United States fell from 32% in 1990 to 17.6% in 2012, while Asia’s portion rose from 31% to 54.7%. During the same period, China’s share of Japanese exports soared from 2% to 18.1%; and exports to Greater China (China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), meanwhile, rose from 16% to 31.9%.

Figure 7. Japan’s Exports to Major Trade Partners as Percentage of Total (2012)

Source: Trade Statistics, Japan Ministry of Finance.

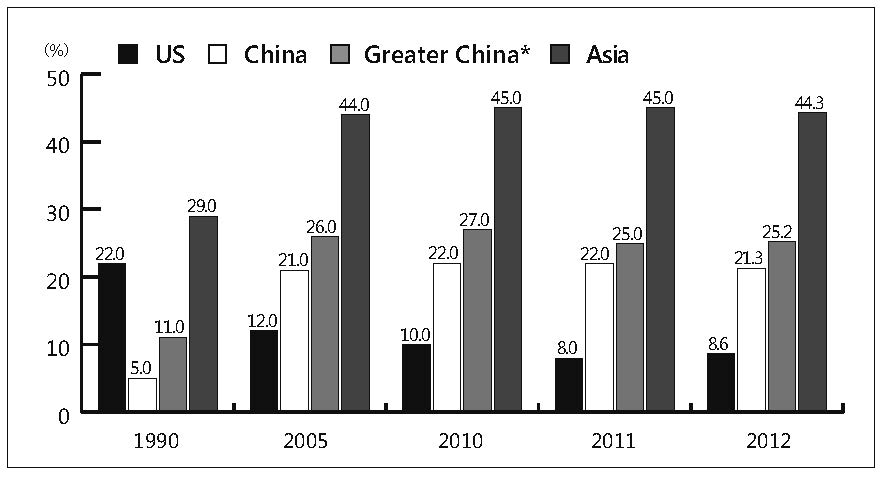

Much the same trend can be seen in Japan’s imports. From 1990 to 2012, the share from the United States fell sharply, from 22% to 8.6%, while the contribution of Asian goods rose from 29% to 44.3%. Here, too, China’s share grew dramatically, from 5% to 21.3%, and Greater China’s ratio jumped from 11% to 25.2%.

Figure 8. Japan’s Imports from Top Trade Partners as Percentage of Total (2012)

*China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan

Source: Trade Statistics, Japan Ministry of Finance.China has emerged as an economic powerhouse that supports the global economy not merely with its labor force but also with its huge and rapidly developing market, and now the progressive integration of the Chinese and Taiwanese economies is further transforming the international economic landscape. Japanese businesses need to adapt by forging new and stronger business alliances with Taiwanese firms already well established in China. Taiwan can be their gateway to the Chinese market by making maximum use of the ECFA to facilitate their expansion. In addition, they should begin to think of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and even Singapore as belonging to a single Greater Chinese economic zone.

Penetrating the Chinese market through Taiwan can be facilitated by forging partnerships with Taiwanese businesses. Today several circumstances are conspiring to encourage the growth of such cross-border ties. One is the conclusion of the ECFA, which seeks to integrate the Chinese and Taiwanese economies and create a free trade zone. Another is the development of increasingly complementary relationships between Japanese and Taiwanese business. The Taiwanese government is also actively promoting Japan-Taiwan cross-border alliances. And last but not least is the affinity so many Taiwanese feel toward the Japanese people; indeed, in a 2010 public opinion survey carried out by the Interchange Association, which represents the government of Taiwan in Japan, 52% of respondents chose Japan as their favorite country.

Leveraging Both Sides’ Strengths

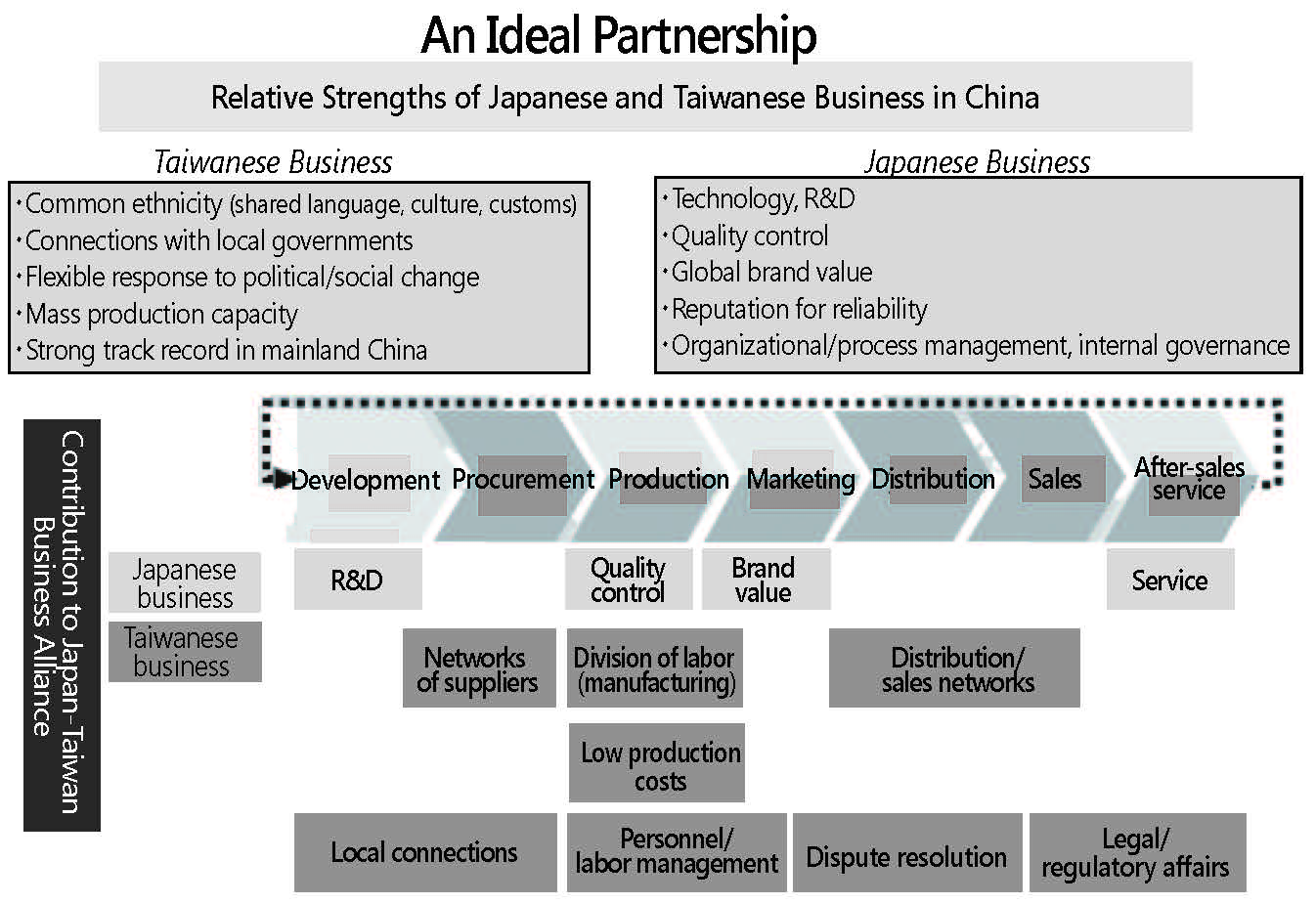

To operate effectively in the Chinese market, the partners in a Japan-Taiwan business alliance must establish a complementary relationship that makes the most of each side’s relative strengths. Let us examine what Japanese and Taiwanese businesses can bring to the table when it comes to doing business in China.

Chief among the advantages Taiwanese business enjoys are its global value chain; its affinity toward Japan; its networks of interpersonal relationships and ability to negotiate in a Chinese milieu (including connections with local governments); its relatively advanced industrial technology and fast, low-cost mass-production systems; its ability to tailor its products to the needs of the local market; an impressive track record of achievement in China; the ability to respond flexibly to political and social change; and the ethnicity (language, culture, customs) it largely shares with the mainland Chinese.

Japan, meanwhile, brings its technological know-how and capacity development and innovation; top-notch quality control; brand recognition and value on a global level; an international reputation for reliability; and advanced organizational management, process management, and internal governance systems.

The key to successful business alliances between Japanese and Taiwanese firms is a rational division of labor that leverages the relative advantages of each side at various stages, from research and product development to procurement, production, marketing, distribution, sales, and after-sales service, as illustrated in Figure 9. Simply put, this means building an integrated regional value chain that brings Japanese technology and product design to the emerging Asian markets—China’s in particular—using materials and parts sourced from Taiwan, test-marketing on the Taiwanese market, and tapping the business networks of Taiwanese companies operating overseas.

Figure 9. Japan-Taiwan Business Alliance

The liberalization of trade and investment between China and Taiwan offers a wealth of opportunities for Japanese businesses with Taiwan connections. Those that have been providing products and services for the Taiwanese market can make use of the know-how, business partnerships, and human resources they have acquired in the process to secure a role for themselves in the cross-strait development projects that are expected to emerge as liberalization of China-Taiwan trade and investment progresses, thereby accelerating their expansion into China. Corporations that have partnered with Taiwanese companies in the manufacture of products for global export, whether through joint development or outsourcing of components, will be able to secure a cost advantage over the competition by selling products on the Chinese market that have been assembled in China. Japanese businesses with corporate clients in Taiwan may now find it strategically advantageous, given the favorable winds generated by the ECFA, to use Taiwan as a base for development and export.

With a few exceptions, small and midsize Japanese businesses have made relatively little progress expanding overseas, owing to limited resources and the risks of launching business operations in an unfamiliar environment. But given the rapid improvement in cross-strait relations in recent years, these smaller businesses may find they can acquire the resources they need to penetrate the Chinese and other emerging markets by forming business alliances with Taiwanese counterparts, making the most of each side’s strengths and compensating for one another’s weaknesses.

Of course, any Japanese business considering such an alliance needs to draw up an individualized blueprint tailored to its own sector and business strategy, with the lessons of previous partnerships in mind. The choice of a partner is also critical, as the success of any business alliance depends on finding a good fit in terms of mutual trust, the potential for a mutually complementary relationship, and the ability to embrace a common vision at all levels of management.

Conclusion

In Taiwan’s January 2012 presidential election, incumbent President Ma Ying-jeou of the Kuomintang, with Wu Den-yih as his running mate, fended off a challenge from the opposition to secure a second term. Setting forth his policy agenda for the next four years, Ma stressed his administration’s ongoing commitment to preserving the political status quo in in the Taiwan-China relationship based on the “three no’s” (no unification, no independence, no use of force). At the same time, he pledged to continue his policy of reconciliation centered on stronger economic ties by pushing for early negotiations oriented to further liberalization, including tariff reductions, under the ECFA.

On the Chinese side, at the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in November 2012, party leaders called on Taiwan to join in discussions for a peace agreement (activity report by then General Secretary Hu Jintao) and voiced Beijing’s intent to wrap up follow-up talks for tariff reductions and deregulation under the ECFA by the end of 2013 (press conference by then Minister of Commerce Chen Deming).

This was a time of rising tensions between Japan, China, and Taiwan over the Senkaku Islands (referred to as the Diaoyu Islands in China and the Diaoyutai Archipelago in Taiwan). In August 2012, President Ma proposed an East China Sea Peace Initiative to preserve peace and stability through economic cooperation aimed at sustainable marine development for the mutual benefit of all three parties. Urging all sides to refrain from escalating the conflict and to commit themselves to a peaceful resolution, he called for the adoption of an East China Sea “code of conduct” based on a trilateral consensus and the creation of a formal mechanism for joint development of resources in the East China Sea.

Ma has described Taiwan’s relationship with Japan as a “special partnership” that he wishes to maintain and has pledged not to side with Beijing against Tokyo over the Senkakus. On April 10, 2013, Japan and Taiwan concluded a fisheries agreement, which went into effect a month later. On November 5, 2013, the Taiwanese and Japanese negotiating authorities signed five documents agreeing to boost cooperation on electronic commerce, patent priority claims, pharmaceutical regulations, railways, and maritime search and rescue. On November 28, they signed a memorandum of understanding on financial supervision aimed at maintaining the health of the financial system through exchanges of information between financial authorities.

These developments have set the stage for further progress in the development of Japan-Taiwan relations. In such an environment, partnerships between Japanese and Taiwanese industry can function not only to maintain strong bilateral ties at the private level but also to help stabilize political and diplomatic relations in the region.

In our age of globalization, the economic dynamism of China and other emerging markets is the engine that powers the global economy. Japanese businesses need to understand which way the wind is blowing and actively explore the possibilities for tapping into Asia’s emerging markets by leveraging its deep ties with Taiwanese industry to build a new type of cross-border business alliance.