- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

View from the Social Sector: Engaging with Businesses for Sustainability

June 12, 2018

Ensuring the sustainability of humanity’s social and economic systems is the key challenge facing international society in the twenty-first century. Behind this new emphasis on sustainability is widespread and growing concern over such global problems as climate change, loss of biodiversity, poverty, wealth disparities, hunger and malnutrition, gender inequality, and unsustainable consumption and production practices. In September 2015, the UN General Assembly acted on these concerns by unanimously adopting Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development , a document setting forth 169 targets grouped under 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

No one sector of society is capable of solving any of these global issues on its own. Real progress toward attaining the SDGs will require contributions from government, private businesses, international organizations, and the social sector comprising nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations (NPOs/NGOs). Moreover, in addition to doing their part individually, these sectors must find ways to surmount their differences and work together collaboratively.

In the following I examine the evolving relationship between industry and the social sector from the perspective of the latter and assess the outlook for collaboration in the age of the SDGs.

A Changing Relationship

Until fairly recently, most people regarded the goals and activities of profit-making businesses as fundamentally incompatible with the aims of the NPOs/NGOs dedicated to addressing social issues. However, the relationship between the two has changed dramatically in the past 20-30 years. The biggest reason for that change is the growing concern over sustainability.

As globalization advanced in the 1990s, society became ever more aware of such global threats to sustainability as climate change, loss of biodiversity, water issues, human-rights abuses, and poverty. As powerful multinational corporations extended their supply chains to the developing world, they came under mounting criticism for causing environmental degradation and condoning serious labor and human-rights abuses. International NPOs and NGOs helped bring these problems to light, fueling worldwide demands for corporate social responsibility.

Meanwhile, it became increasingly apparent that the best hope for seriously tackling such global problems was the formation of cross-sector partnerships among government, private industry, and the social sector, which would allow for the mobilization of the private sector’s financial resources, innovative capacity, and business models.

Around the beginning of this century, businesses began instituting stronger CSR policies and programs, and before long they were integrating social responsibility into their core management strategies. This set the stage for the development of strategic partnerships between businesses and nonprofits. Recent years have also witnessed changes in the basic relationship between private industry and society, as exemplified by the concept of “creating shared value”ーthat is, contributing both to corporate value and to the public good by responding to the needs of society. All of this has propelled significant changes in the relationship between the corporate and social sectors.

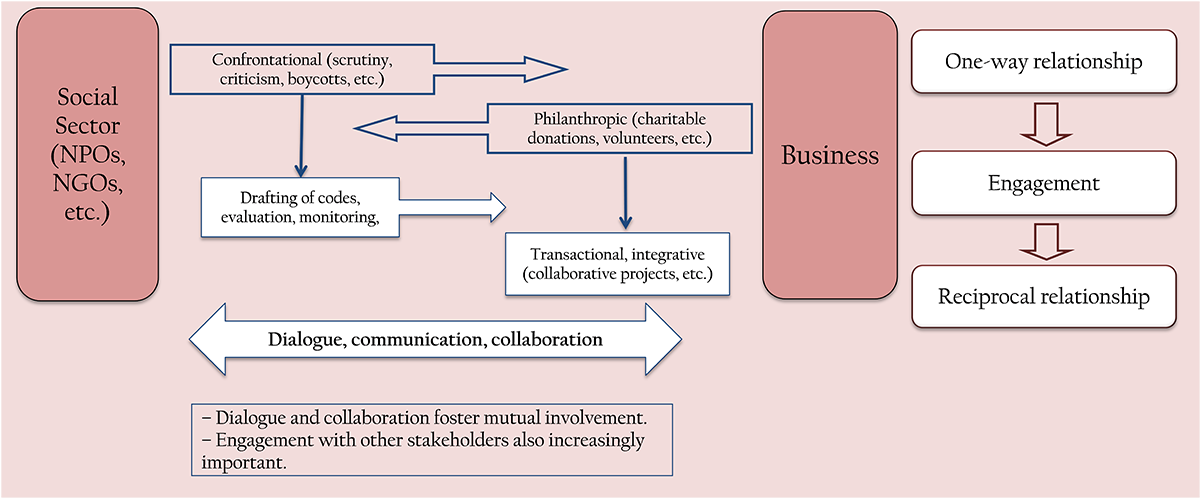

From the perspective of the latter, the change might be described as follows. In the past, interaction between the two sectors tended to be either confrontational or philanthropic in nature. Nonprofits (insofar as they concerned themselves with the private sector at all) were either industry gadflies that criticized, scrutinized, and campaigned against businesses or passive recipients of corporate philanthropy. In either case, it was basically a one-way street. In recent years, however, more reciprocal modes of interaction have come to the fore as organizations in the social sector have engaged with businesses toward the common goal of a sustainable future. In some cases, the dialogue has progressed to collaboration. This is not to say that the confrontational and philanthropic relationships of the past have disappeared. It would be more accurate to say that the modes of interaction between the two sectors have diversified. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution schematically.

Figure 1. Change in the Relationship between the Social and Business Sectors

In the following section, I examine these modes of engagement more closely.

Pressuring Industry to Change

Many nonprofits and other social-sector organizations around the world are advocacy groups dedicated to protecting either the environment or society’s vulnerable groups, such as indigenous peoples, women, the disabled, sexual minorities, children engaged in child labor, exploited workers, and local farmers whose livelihoods are threatened by resource exploitation or agribusiness. As such, they saw it as part of their mission to speak out against companies in an effort to correct management policies that threatened the environment or violated the rights of these vulnerable groups. Recent years, though, have seen the proliferation of social-sector groups committed to working more collaboratively with business in the “creation of shared value,” as noted above, to ensure that the interests of the environment and socially vulnerable are represented. This collaborative trend has been accelerating since the adoption of the SDGs, with their emphasis on “leaving no one behind.”

Seminal Campaigns

The international movement to promote corporate social responsibility grew out of the social sector’s scrutiny and public criticism of corporate conduct. In the environmental realm, we can clearly trace this process as it unfolded in the wake of a disaster of historic proportionsーthe Exxon Valdez oil spill.

In 1989, the Exxon Valdez , an oil tanker owned by Exxon Shipping Co., ran into a reef along the southern coast of Alaska and spilled millions of gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound, causing massive damage to the coastal environment. In the wake of the accident, environmental activists and scientists banded together and launched Ceres, an organization whose mission is to “mobilize investor and business leadership to build a thriving, sustainable global economy.” The Ceres Principles, a 10-point code of corporate environmental conduct (originally called the Valdez Principles), was released in 1989. Japanese environmentalists jumped on the bandwagon in 1991 with the formation of the Valdez Society, aimed at pressuring Japanese companies to embrace the same principles. Ceres also gave rise to the Global Reporting Initiative, which published detailed guidelines for sustainability reporting.

In the area of labor and human rights, the pivotal event in the evolution of CSR was the boycott of Nike products in the mid-1990s. For years the American athletic-apparel giant had been under scrutiny for contracting with Asian sweatshops, including some accused of child labor. However, Nike had denied any responsibility for the labor practices of its suppliers. Finally, a coalition of human-rights groups and other nonprofits organized a global boycott of Nike products, which won widespread support among students and consumers. Faced with falling revenues and a serious image problem, Nike finally drew up a code of conduct applicable to all companies in its supply chain and promised to take active steps to improve working conditions. This policy change was catalytic, accelerating the adoption of supply-chain codes at both the company and industry levels.

Drafting Guidelines with Multi-Stakeholder Input

It was around this time that social-sector organizations got involved in the drafting of guidelines and codes of conduct designed to promote socially responsible behavior in the business sector. Among these were Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000), a set of international standards for labor and human rights hammered out by a diverse group of stakeholders that had united around the issue of child labor; the ETI Code of the Ethical Trade Initiative, comprising NGOs, labor groups, and major industry players; the aforementioned sustainability reporting guidelines published by the Global Reporting Initiative; and AccountAbility 1000 (AA1000), a framework of principles and guidance for CSR management. These guidelines were drawn up under the leadership of the social sector through a process of multi-stakeholder consultation, with industry well represented. NPOs and NGOs also participated as key stakeholders in the compilation of ISO 26000 offering guidelines on corporate social responsibility adopted by the International Organization for Standardization in 2010.

Another focus has been the development of certification systems for identifying products that meet specified standards for social responsibility and environmental sustainability. Perhaps the best known are the Fairtrade Certification Mark (Fairtrade International) and the World Fair Trade Organization Mark. Similarly, the Forest Stewardship Council offers FSC certification for sustainable forest products, the Marine Stewardship Council awards the MSC label for sustainably harvested seafood, and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil offers RSPO certification. All of these systems were developed through an extended process of consultation among representatives of industry and other stakeholder groups under the leadership of NGOs.

CSR Scoring and Ranking

Another way in which the social sector helps to advance CSR is by working with organizations that conduct research and analysis to evaluate and rank businesses in terms of sustainability. In the West, socially responsible investing has picked up dramatically since the 1990s, and this trend has created a demand among institutional investors for information on corporate performance vis-à-vis environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. Many of the groups that supply such information were initially established by nonprofits. EIRIS, one of the best-known sources of SRI research and analysis, is a nonprofit linked to a network of NGOs worldwide. CDP (originally the Carbon Disclosure Project) is a nonprofit organization established in 2000 by some of the world’s top institutional investors for the purpose of promoting corporate disclosure of information pertaining to climate change. Today, almost all of the world’s top socially responsible institutional investors are signatories or members of CDP.

Around the year 2000, a new tool for SRI emerged in the form of “social return on investment” (SROI), a method of calculating investment value using various environmental and social indicators in addition to the usual financial information. Since then, the method has continued to evolve. In Japan, the nonprofit SROI Network Japan offers SROI training and information.

Another approach the social sector uses to promote CSR is to draw up a set of indicators independently and apply them to corporate data to rate companies’ social and environmental performance. For example, in 2013, the global NGO Oxfam launched Behind the Brands, an initiative for rating the 10 biggest food and beverage companies in terms of sustainability and social responsibility. [1] The project makes use of social media to facilitate two-way communication with consumers. It also gives the businesses it rates an opportunity to respond and communicate online. According to a 2017 analysis by Oxfam, all 10 companies improved their overall performance between 2013 and 2016.

The Fair Finance Guide adopts a comparable approach, using its own index to rank banks according to their investment policies. In Japan, three environmental NGOs joined forces to launch a parallel project under the name Fair Finance Guide Japan. Another program that has attracted widespread interest is Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, a joint undertaking by a group of nonprofits and institutional investors to develop industry-specific human-rights performance indicators. In 2016, CHRB launched its first pilot, targeting 98 companies in the areas of agricultural products, apparel, and extractives. [2]

Japan’s Low-Key Activism

The evolution of CSR in Japan over the past 15 years has been driven in large part by the business community itself; the role of government, consumers, and the social sector has been relatively limited, and Japanese nonprofits dedicated to pushing industry for change has been relatively few and far between. Rather, members of Japan’s social sector often participate actively as partner organizations or members of a global network, as in the case of Fair Finance Guide Japan (discussed above). Another noteworthy example is the Japan Campaign to Ban Landmines, which was among the first groups to target the investment policies of financial institutions. Launched in 1997 as part of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, JCBL has played an active role in the global effort to abolish landmines and similar anti-personnel weapons on humanitarian grounds. Since 2009, it has been working with the Cluster Munition Coalition to halt the flow of investment funds to companies that manufacture cluster bombs.

As SRI gains momentum in Japan, dialogue between institutional investors and the social sector is gradually picking up as well. Unfortunately, few Japanese NGOs have the capacity and resources (especially overseas experience, expertise, and networks) to generate the kind of evidence needed to influence corporate conduct. Yet this sort of advocacy is one of the most important roles of the social sector today, integral to its very raison d’être. The key to strengthening this function may lie in continued cooperation with other sectors, including partnerships with think tanks and other research organizations, as well as ongoing dialogue and collaboration with institutional investors committed to ESG investment.

Collaborating with Business

Now let us move on to a different mode of interaction, one in which the social and business sectors overcome their differences and engage in successful collaboration. As a framework for this discussion, I would like to offer a brief introduction to the “three stages of collaboration” set forth in James Austin’s book, The Collaboration Challenge: Nonprofits and Business Succeed through Strategic Alliances . [3]

Austin’s Three Stages of Collaboration

According to Austin’s framework, the first stage in the evolution of a collaborative relationship between the business and social sectors is “philanthropic,” where the relationship pivots on charitable support provided by companies. This can take a variety of forms, including financial contributions and grants, in-kind donations, employee participation in volunteer activities, and participation in campaigns or charitable events planned by NPOs and NGOs. These days, it also increasingly takes the form of pro bono professional services provided by companies or their experts.

Stage two is the “transactional” phase, when nonprofits and businesses build mutual understanding and trust through the beneficial exchange of resources. Some typical examples are cause-related marketing, in which companies donate a part of their proceeds to a nonprofit or sponsor a social-sector event. This represents a step forward from philanthropy in terms of reciprocity.

Stage three is the “integrative” phase, when the two sides interact more intensively and begin to combine their resources to create shared value. At this stage, organizations work in an integrated fashion on the planning and implementation of projects, development of products or designs, or other collaborative undertakings.

Figure 1 helps to illustrate the dynamics of this continuum. In this scheme, integration is not invariably the final destination. It is not unusual for a business to employ multiple modesーfor example, engaging in integrative partnerships on one front while providing pro bono services on another. What we can say is that relationships between the business and social sectors are becoming increasingly strategic and diverse. (Note that here, I reserve the term “collaboration” for transactional and integrative relationships.)

Development of Cross-Sector Collaboration in Japan

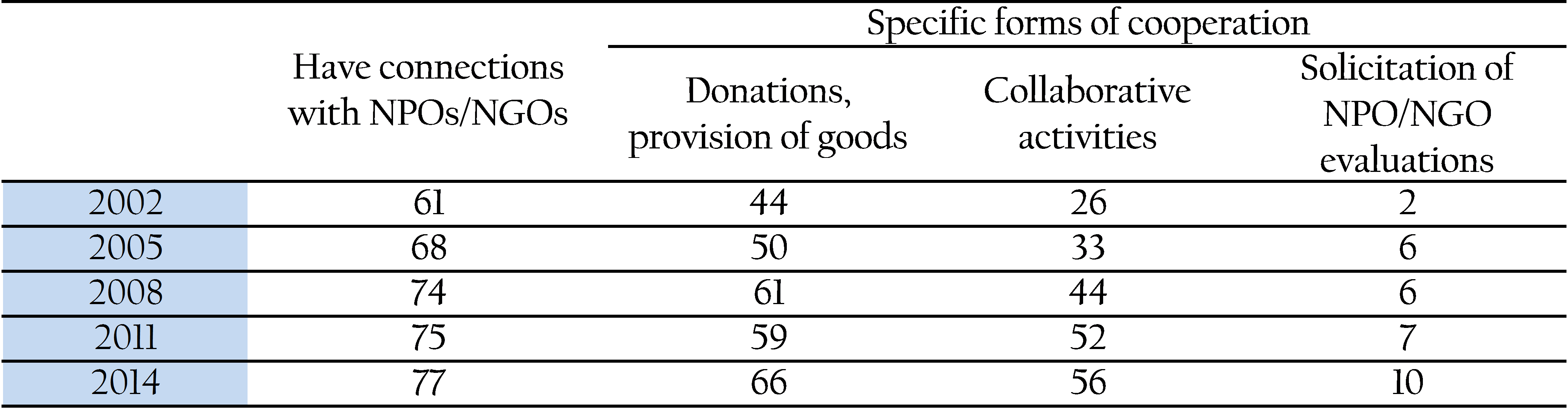

Cross-sector collaboration has made considerable progress in Japan, especially in comparison with the pressure strategies discussed in the previous section. The results of the annual Survey on Corporate Philanthropic Activities, conducted since 1991 by Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) and the 1% Club, show a continuous increase in the percentage of companies that maintain connections (points of contact) with at least one NPO. In terms of specific modes of interaction, charitable donations, collaborative activities, and CSR evaluations by NPOs or NGOs all appear to be gaining ground (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Japanese Businesses’ Reported Relationships with the Social Sector (%)

Comparable longitudinal surveys of the social sector are few and far between, but the Data Book on NGOs 2016 , published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, offers some insight on the basis of a 2015 survey conducted by the Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC) and a similar survey conducted in 2011. [4] Corroborating the results of the Keidanren survey, the report notes the increase in joint research projects and other collaborative programs since around 2000, when CSR began to gain traction in Japan. In the 2015 JANIC survey, about 20% of the responding NGOs indicated that they were involved in CSV (creating shared value) partnerships. Those organizations reported annual donations of about 280 million yen on average. On the other hand, organizations whose relationships with business were of a charitable or philanthropic nature averaged only about 13 million yen in annual donations. This suggests that CSV alliances may be difficult to build for smaller NPOs and NGOs.

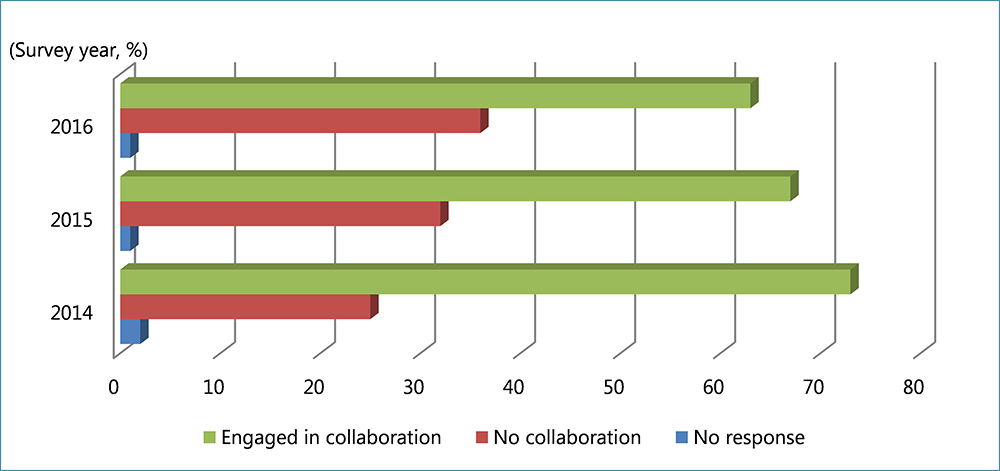

Interestingly, the results of the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research CSR Survey, conducted annually since 2013, suggest a decline in collaboration in recent years (Figure 3). In the Foundation’s survey, the percentage of responding companies reporting collaboration with the social sector dropped a full 10 points between 2014 and 2016.

Figure 3. Percentage of Companies Engaged in Collaboration with the Social Sector (2014-16)

One explanation may be that, while collaboration has deepened, as suggested by the JANIC survey, there are fewer projects underway. In other words, the results of the two surveys, taken together, may be indicative of a shift from quantity to quality. When businesses are switching from philanthropic support to CVS-style collaboration, they may be inclined to choose their social-sector partners strategically, targeting NPOs and NGOs with substantial resources and capacity.

Focusing on domestic activity, we see clear signs of diversification in Japanese industry’s assistance to and cooperation with nonprofits, including growing support for capacity building among community groups dedicated to problem solving at the local level. Further research is needed to clarify these trends and their relationship to one another.

Conclusion: Collaboration in the Age of the SDGs

Since the adoption of the SDGs, understanding of social and sustainability issues has continued to deepen among corporate managers and business consultants. In addition, the growth of socially responsible investing has led to an increase in dialogue between companies and investors on social and environmental issues. But compared with nonprofits in the West, Japan’s social sector has been slow to build alliances with investors. As a result, even in areas where SRI is having an impact, the social sector has not been a prominent presence. Under these circumstances, the most effective means by which Japan’s social sector can contribute to the development of a sustainable society are to (1) ensure maximum participation by the socially vulnerable and make sure that their voices are heard, (2) pursue cooperation with and among various sectors and stakeholders, and (3) collect data and make evidence-based recommendations from a civil-society vantage point.

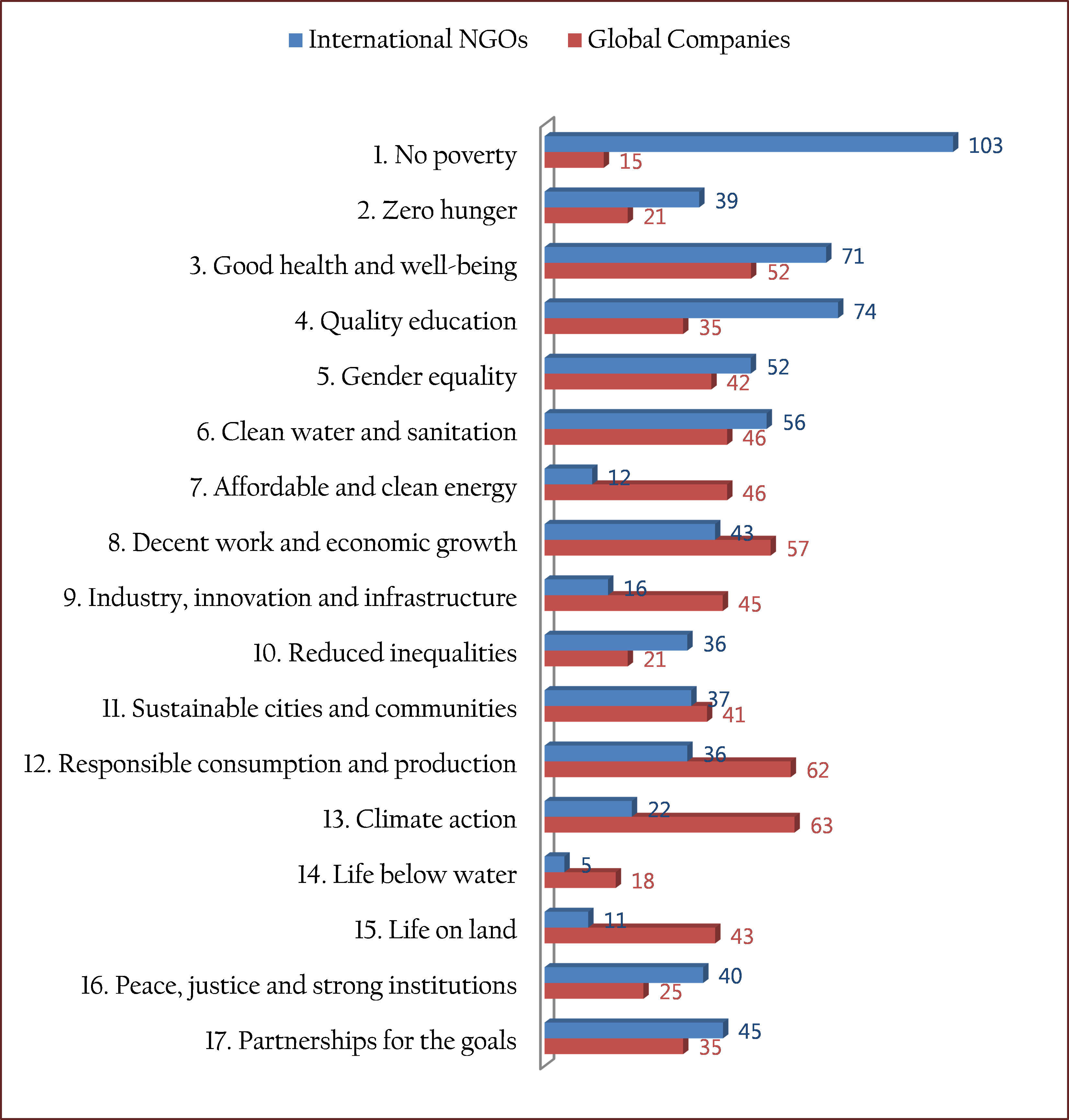

With respect to (2), cooperation with and among various sectors and stakeholders, I would like to stress the need for the business and social sectors to complement one another’s strengths and interests as they work together to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The results of the abovementioned 2016 JANIC survey and a recent report by the Business Policy Forum, Japan, [5] highlight basic differences in the two sectors’ SDG priorities. Both international NGOs and businesses tend to place high priority on goal 3 (good health and well-being), goal 5 (gender equality), goal 6 (clean water and sanitation), and goal 11 (sustainable cities and communities). On the other hand, NGOs are far more focused on goal 1 (no poverty) and goal 4 (quality education) than businesses, while industry naturally places greater emphasis on goal 7 (affordable and clean energy), goal 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure), goal 12 (responsible consumption and production), and goal 13 (climate action). To achieve the SDGs, it is important to develop modes of collaboration that acknowledge and make the most of the two sectors’ different strengths and interests. Of course, cooperation should not be limited to the corporate and social sectors but should encompass all segments of society, including government, academia, organized labor, and financial institutions. As relatively disinterested parties, NPOs and NGOs can be effective mediators, facilitating cooperation among stakeholders and sectors with divergent interests. Intermediate support organizations, with their far-flung networks, have a particularly important role to play in this regard.

A good example of (3), collecting data and making evidence-based recommendations, is Oxfam International’s Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index, a global ranking of 152 countries according to their policies to reduce the gap between rich and poor. [6] By evaluating government policy from a civil-society perspective, such an index is sure to illuminate aspects of economic inequality that are difficult to gauge from government statistics alone. To perform this function, the social sector needs to work actively, in cooperation with think tanks and other research organizations, to gather and analyze information often missed by government statistics, especially data pertaining to living, working, and environmental conditions at the local level.

Figure 4. The SDGs Addressed by International NGOs and Emphasized by Global Companies

To conclude, I offer the following recommendations for more effective collaboration between businesses and the social sector.

● Treat one another as partners at each stage of the process, from identification of issues to project planning, rule making, and program evaluation.

● Make the most of the social sector’s local expertise and knowledge of conditions on the ground, especially when it comes to gauging human-rights risks in specific countries, sectors, and areas.

● Be honest and share your goals with one another to nurture mutual understanding and trust.

● Link the partnership to the creation of new value on both sides.

Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals will require real change, not just an extension of tried-and-true strategies. Business and the social sector alike will need to rethink the way they operate and pioneer innovative modes of collaboration keyed to the needs of people, communities, and society as a whole.

[1] https://www.behindthebrands.org .

[2] See https://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2015/089_summary.pdf , p. 12.

[3] James E. Austin, The Collaboration Challenge , Jossey-Bass, 2000.

[4] http://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000150460.pdf .

[5] http://www.bpfj.jp/act/download_file/98193838/74940435.pdf , p. 15.

[6] https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/commitment-reducing-inequality-index .