- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Tools for Jump-Starting CSR: Analysis of the Tokyo Foundation’s Third CSR Survey

September 19, 2017

In the 2014 and 2015 editions of the Tokyo Foundation CSR White Paper, based on the CSR research team’s quantitative analysis of survey responses from businesses all over Japan, the authors attempted to communicate the importance of integrating action on social problems into a company’s business operations, stressing the idea of CSR as synonymous with good management. We had found that many Japanese businesses regarded “social responsibility” as a simple matter of compliance or attention to environmental issues. We also found among businesspeople of a certain age (especially top executives) a lingering tendency to equate CSR with charitable donations and philanthropic activities divorced from the company’s core business.

Our research team was convinced that a corporation’s social responsibility, like the social responsibility of any organization, was essentially a matter of responsiveness to the needs of a changing society. With this definition in mind, we showed how integration of CSR into a company’s business not only benefited society but also helped to build and sustain corporate value by creating new business opportunities and reducing business risks.

Even in the few years since the publication of the first Tokyo Foundation CSR White Paper, this perception has spread through much of the Japanese business community, thanks in large part to such external circumstances as the rise of integrated reporting, the growth in ESG investing (investment decisions that incorporate environmental, social, and governance factors), and new corporate governance rules and guidelines, including the appointment of outside directors. Yet the more this awareness spread, the more queries we received from businesses anxious to know what, specifically, their own companies should do, in terms of management, operations, and human resources, to integrate social action into their business and put into practice the principle that CSR is synonymous with good management.

In answer, we have made a point of including case studies in each CSR White Paper. In our previous edition we zeroed in on two stages in the CSR process that seem to pose special challenges for Japanese companies: identifying social issues to tackle and internalizing those challenges as an organization. In our most recent corporate survey, we have followed up on these findings by exploring the ways that successful Japanese companies go about identifying and embracing challenges.

I. ABOUT THE CSR CORPORATE SURVEY

A. Design of the Survey

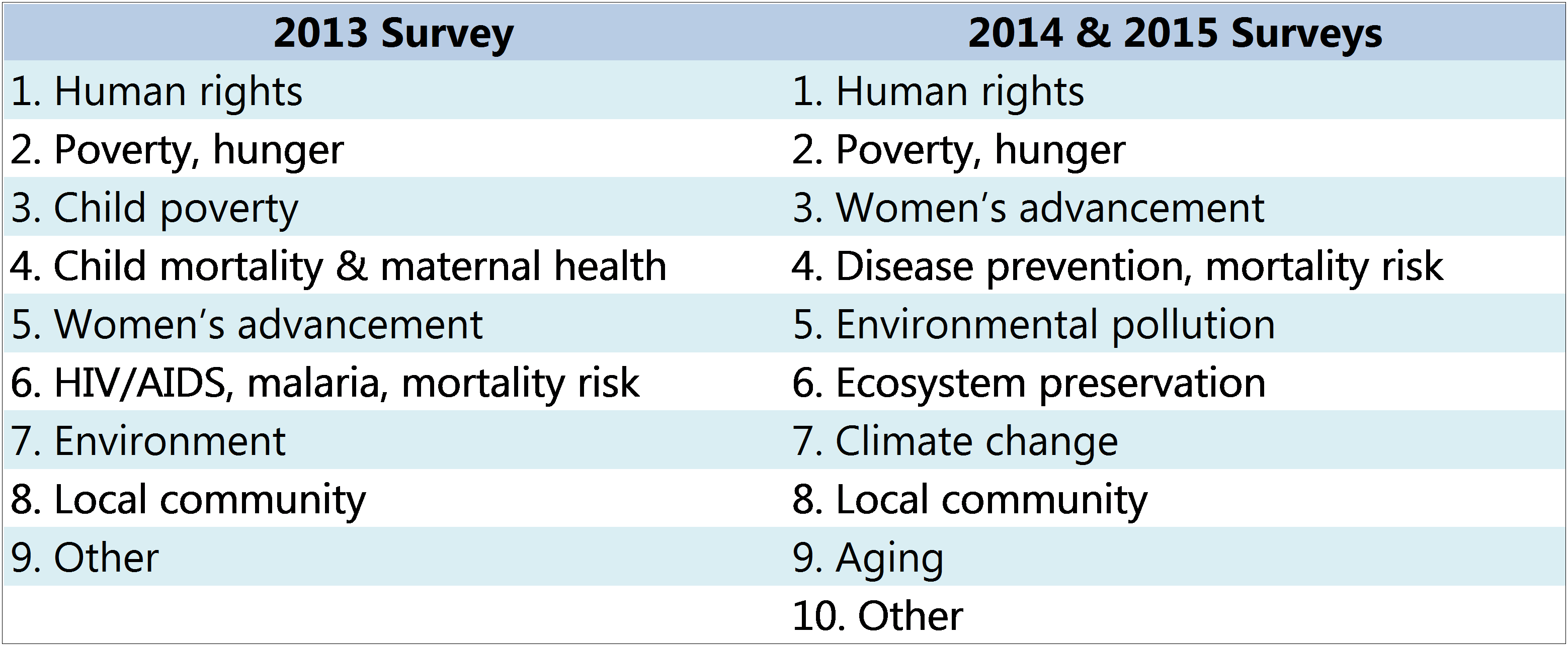

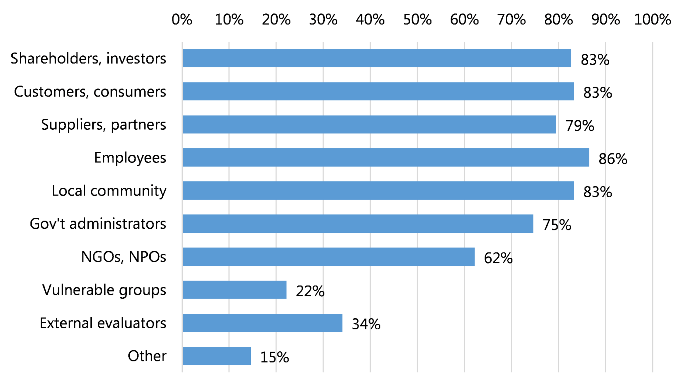

The Tokyo Foundation has conducted three CSR surveysーin 2013, 2014, and (most recently) 2015. Throughout, our basic approach has been to structure the survey around the issues facing society. Most surveys on this theme group their questions under types of corporate activity, but we felt that the raison d’être of CSR was the resolution of social issues. Accordingly, we grouped our questions under different issue categories, with Japanese companies being asked to provide separate responses for their domestic and overseas initiatives. In the latest survey, we classified social issues under 10 headings (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Reorganization of Social Issue Categories

The 2014 CSR White Paper, based on the first (2013) survey, highlighted the need for companies to take a more integrated approach to CSR, addressing social issues while simultaneously contributing to the business itself. Our 2015 report profiled companies that practice CSR integration and sustainability and identified responsiveness to change as a key common trait. The data from the 2014 survey, as well as our case studies, revealed that responsive companies excelled at the identification and internalization of CSR challenges. They also revealed areas in which Japanese companies need work.

In our previous report, we were able to link the problems Japanese companies encounter in their CSR programs to three basic stages in the CSR process: identifying social issues to address, internalizing the challenge as an organization, and taking action to address the issues. We found that many companies hit obstacles at some point before the action stage. Lacking the systems or know-how needed to get them “over the hump,” they fail to make smooth progress in addressing social issues.

The problems start with the identification of issues to be addressed. A company cannot even begin to engage in CSR unless it can identify the concerns of society’s diverse stakeholders. But management has few opportunities to learn about such issues during the course of routine business operations. The average company’s contact points with the broader community are surprisingly limited. Engaging in dialogue with internal and quasi-internal stakeholders, such as employees, shareholders, and partners, is helpful but not sufficient for this purpose.

This points to the need for companies to actively create opportunities for broader dialogue. By communicating with a variety of external stakeholders, companies can gain in-depth information on a greater range of issues and learn what society expects from them. Two-way communication is as essential to companies as it is to individuals. Our 2014 survey found, however, that businesses had insufficient opportunities for dialogue of this sort.

The second problem pertains to internalization. Having identified an issue to address, a company must have some system or mechanism for embracing and tackling the issue as an organization. In the last survey, we found that many companies experienced difficulties both in promoting CSR awareness among their employees and in establishing concrete company-wide objectives or targets, such as key performance indicators.

The third problem corresponds to the third stage, that of taking action on the issue. We know that Japanese businesses have the technological and organizational capacity to make a real contribution to the resolution of many of these problems. Yet according to our 2014 survey, relatively few had created a process to implement concrete solutions. Advancing to this phase would appear to be a key challenge for Japanese companies.

In short, we found that Japanese corporations had a tendency to get stuck at certain bottlenecks in the CSR process. What tools or strategies are most effective in breaking these impasses?

Our latest corporate survey set out to identify such game changers. The research team came up with a list of likely candidates, including (1) top management’s engagement in CSR, (2) dialogue geared to identifying social issues, (3) human resources development, and (4) CSR governance structure. We then set out to examine each of these factors to see how it correlated with companies’ level of interest in social issues, their implementation of solutions, and a self-assessment of their own CSR efforts. This approach resulted in a substantially longer and more complex questionnaire than those compiled in previous years. Even so, more than 200 companies returned the surveysーan indication of the high level of CSR awareness among Japanese businesses.

The latest survey also added several questions designed to shed light on the nature of companies’ involvement with various social issues. First, we asked respondents to identify the initial impetus that had caused the company to take an interest. We disaggregated the results by issue to determine whether involvement in a given issue was more likely to be triggered by external factors, such as laws and regulations, or internal stimuli, such as employee and managerial input. The hope was that this information could contribute to the process of issue identification and selection.

We also asked companies to rate various aspects of their own CSR efforts during the previous year by indicating whether they were satisfied or dissatisfied, and why. The answers shed further light on the challenges Japanese companies encounter in pursuing CSR.

B. Response

1. Surveys Returned by More than 200 Companies

On August 1, 2015, we sent questionnaires to approximately 2,000 companies by postal mail, using publicly available information. The bulk of recipients were corporations listed on Japan’s stock exchanges, but we sent surveys to a number of leading unlisted companies as well. The initial deadline for submission was September 20; the final deadline was October 31. We received valid responses by post or email from 205 companies. Of these, 129 (63%) had responded to our previous survey, while the remaining 76 (37%) were new participants, indicating a substantial change in the composition of the sample.

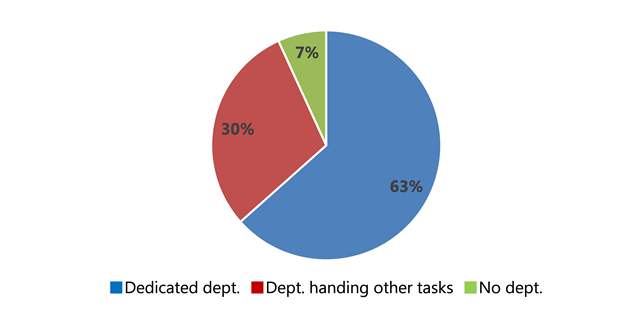

In our latest survey, as in the one before it, we asked whether the company had a department or other unit in charge of CSR. Of the respondents, 63% had dedicated CSR units, while 30% had departments that handled CSR in addition to other duties. Just 7% had no unit in charge of CSR. These results were not significantly different from those of the previous year, when the ratios were 59%, 30%, and 10%, respectivelyーeven though almost 40% of the respondents were new to the study. This suggests that Japanese business has reached a fairly mature stage in the development of their CSR and also appears to affirm the validity of the survey sample. Similarly, we saw no statistically significant change in the percentage of companies with executive-ranking CSR officers or in the number and background of their internal and outside directors.

2. Profile of Responding Companies

As in the past, the targets of the survey were selected with a focus on listed companies; it was not a random sample. Most of the companies that responded can be characterized as large corporations. The mean annual sales for all 205 respondents were 1.13 trillion, and ordinary income averaged 742 million. The average number of employees was about 24,000. A company with this sort of profile would rank somewhere around 130 in the first section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. That said, among the respondents were also companies with fewer than 10 employees.

II. SURVEY FINDINGS

A. Engagement of Top Management

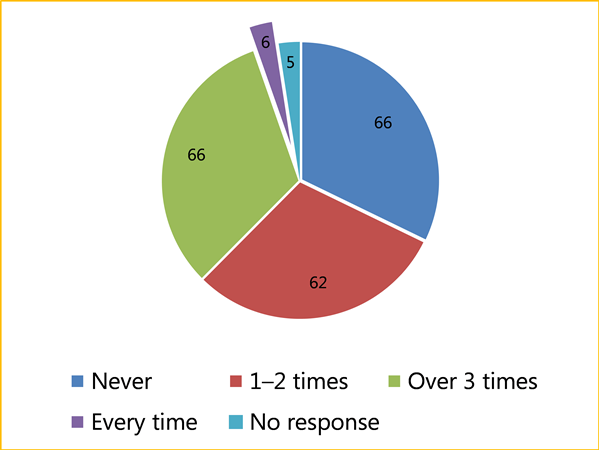

Our latest survey posed multiple-choice questions designed to gauge the degree of top management’s engagement in its company’s CSR program (Figure 2). Just 6 of the responding companies reported that CSR was on the agenda at every board meeting over the past year. At the other end of the spectrum, of the 66 companies that indicated that CSR was never on the agenda, 2 reported that there was no executive participation in the highest-level meetings that did take up CSR matters. We categorized the former 6 companies as “high engagement” and the latter 2 as “low engagement” and compared the state of the two groups’ CSR programs based on the indicators mentioned above.

Figure 2. Degree of Management Engagement in CSR

CSR on Board Meeting Agenda Executive Participation in CSR Meeting

Response to a question (left graph) on the number of times CSR was on the agenda of a board meeting over the past year, and, of companies that never took up CSR at a board meeting, (right graph) on executive participation in the highest-level meeting that did discuss CSR.

Most of the high-engagement companies were corporations in the manufacturing or construction sector. In scale, though, they varied widely, with annual sales ranging from less than 100 million to more than 2 trillion and a workforce ranging from fewer than 10 employees to more than 45,000. We could find no correlation between top-level involvement in CSR and the line or scale of business. However, the high-engagement companies all scored relatively well on the following measures.

First, they all reported a high level of interest in social issues, both within Japan and overseas. On the domestic side, most had already embarked on concrete initiatives in virtually every category. They also exhibited a very high degree of interest in the Sustainable Development Goals (adopted by the United Nations in September 2015) as a thematic framework for social action.

Second, the six high-engagement companies were systematic and diligent when it came to identifying issues and internalizing them at the organizational level. In addition to actively pursuing stakeholder dialogue geared to identifying issues, these six companies distinguished themselves from the typical Japanese corporation by engaging in dialogue with nonprofits, nongovernmental organizations, and socially vulnerable groups. These highly engaged companies were also proactive about supporting CSR through the development of human resources and organizational capacity.

Finally, the high-engagement companies expressed a keen awareness of the positive outcomes of their own CSR programs. In short, these companies are adept at negotiating each phase of the CSR process, from identification and internalization of issues to concrete action, and they have a clear sense of what they have achieved.

The two low-engagement companies, meanwhile, were in the manufacturing and distribution sectors, reported annual sales of roughly 50 billion and 650 billion, and had around 600 and 1,800 employees, respectively. These differences support the previous observation that a company’s size and line of business have little or no bearing on top-level involvement in CSR.

However, the two low-engagement companies both reported the following. They had yet to take action on any social issue, either in Japan or overseas. In other words, they were not yet at the implementation stage in the CSR process. Indeed, neither had progressed as far as identifying or internalizing issues. Although they reported some level of interest in addressing issues in Japan, they had none whatever in overseas problems. One reason for this low level of interest may be that neither company had engaged in any stakeholder dialogue to identify issues. Nor had they conducted CSR training, set CSR objectives, or evaluated their own progress. Without such tools, companies have little to go on when it comes to identifying and internalizing challenges. It is difficult to make real progress on CSR just by blindly feeling one’s way forward.

As the foregoing suggests, the latest survey revealed that top management’s involvement in CSR is an important factor in the progress of a company’s CSR efforts. When CSR comes up at board meetings or in other high-level forums, executives take a personal interest in social issues and get serious about tackling them. Our latest study highlights this virtuous circle.

B. Stakeholder Dialogue

The results of our latest survey indicate that Japanese businesses are making an active effort to engage various stakeholders in dialogue. A full 90% are implementing such dialogue, which can lead to the identification of CSR issues.

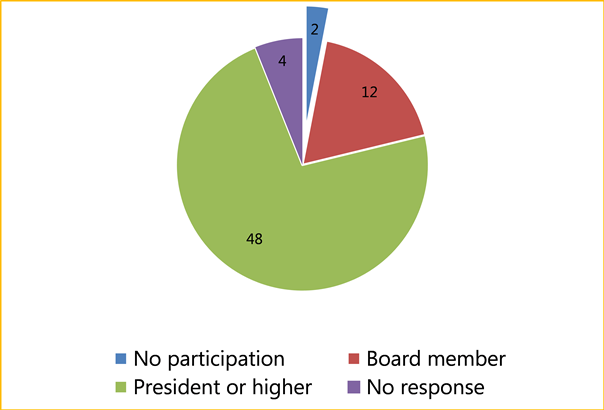

That said, the response varied considerably by stakeholder category (Figure 3). Of the 185 companies conducting stakeholder dialogue, relatively few engaged with socially vulnerable groups or with organizations that conduct independent evaluations. Socially vulnerable groups and external evaluators are both valuable dialogue partners precisely because they tend to provide criticism as well as positive feedback. Meaningful stakeholder dialogue takes a certain amount of courage. One can understand the tendency to avoid engagement with groups whose viewpoint may conflict with management’s, but their input is needed to gain a broader perspective on and fuller understanding of the issues facing society.

Figure 3. Stakeholder Dialogue Partners

Percentage of companies conducting stakeholder dialogue with specific partners (multiple-response format).

Dialogue with NGOs and NPOs also remains insufficient overall. It is encouraging to see that the majority of responding companies, 62%, are engaged in such dialogue, but a more appropriate figure would be at least 75%ーthe same portion of companies engaged in dialogue with regulators and other government administrators. That would be a sign of balanced participation by all three sectors: business, civil society, and government.

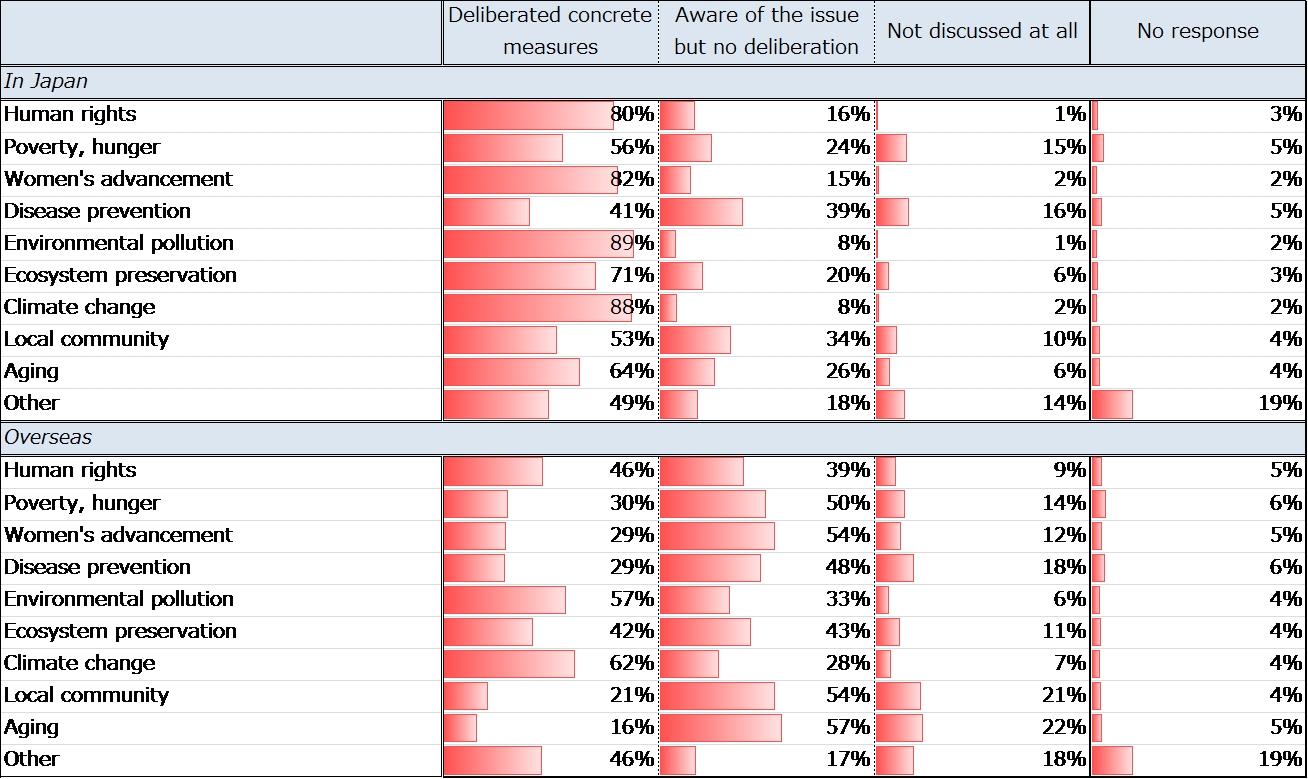

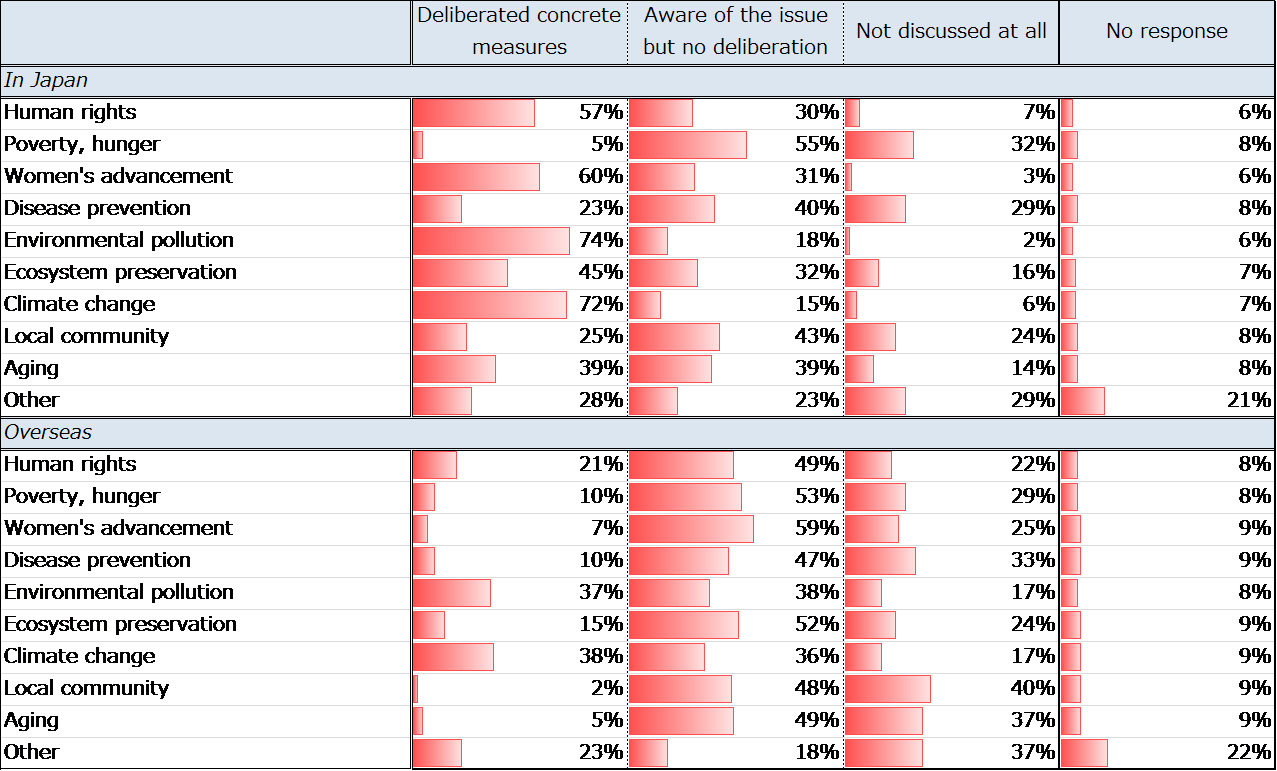

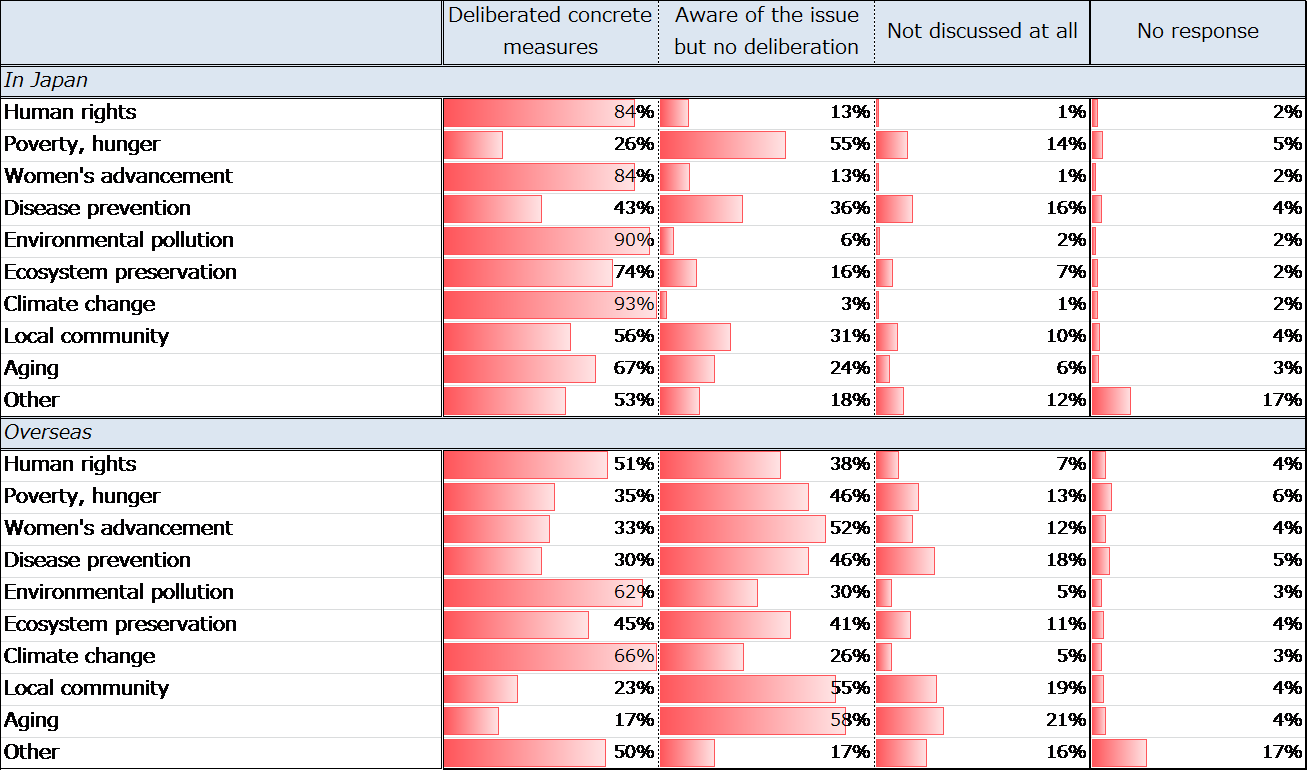

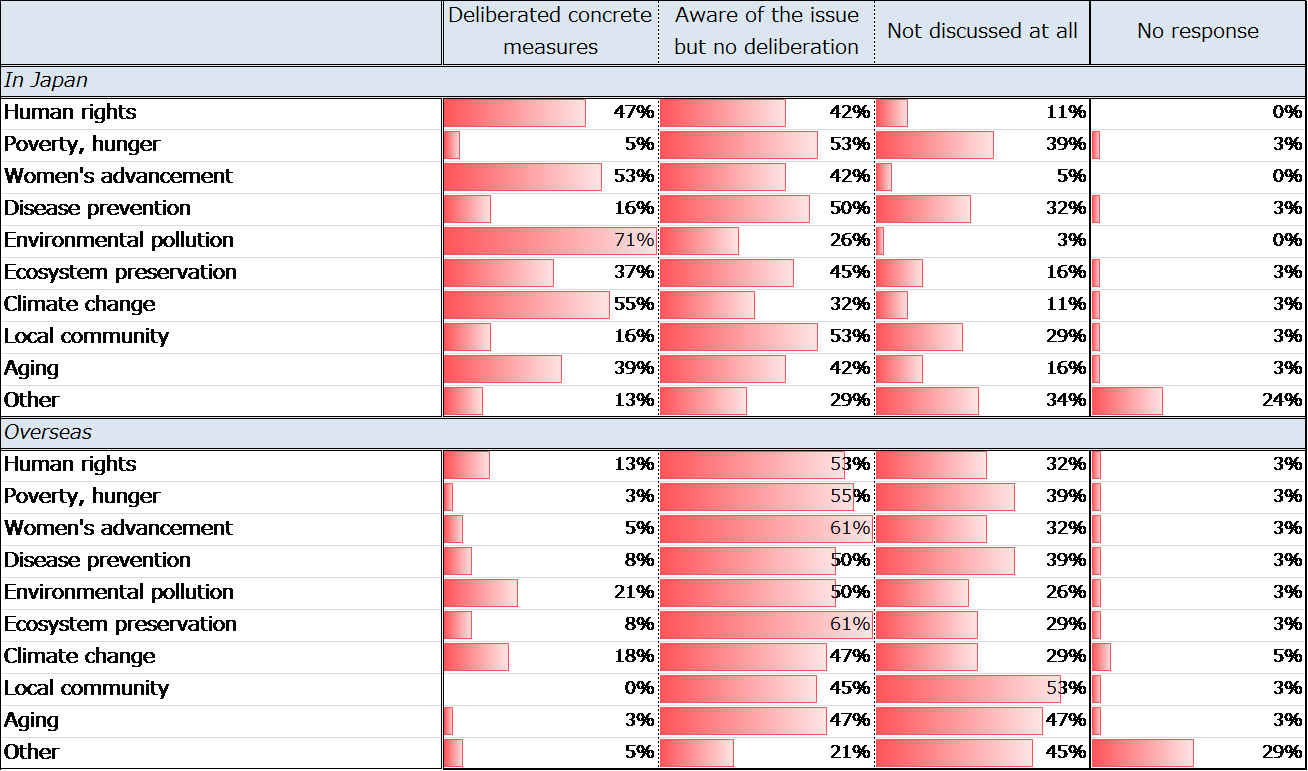

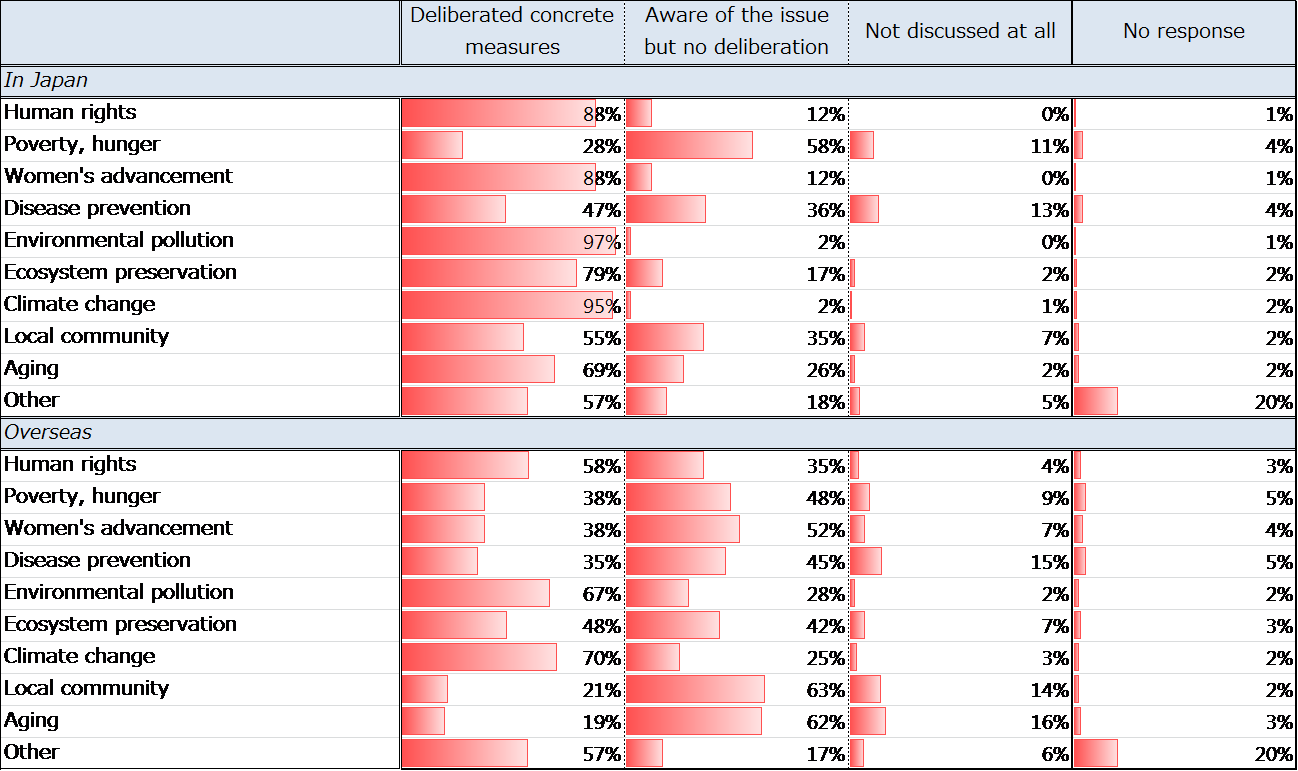

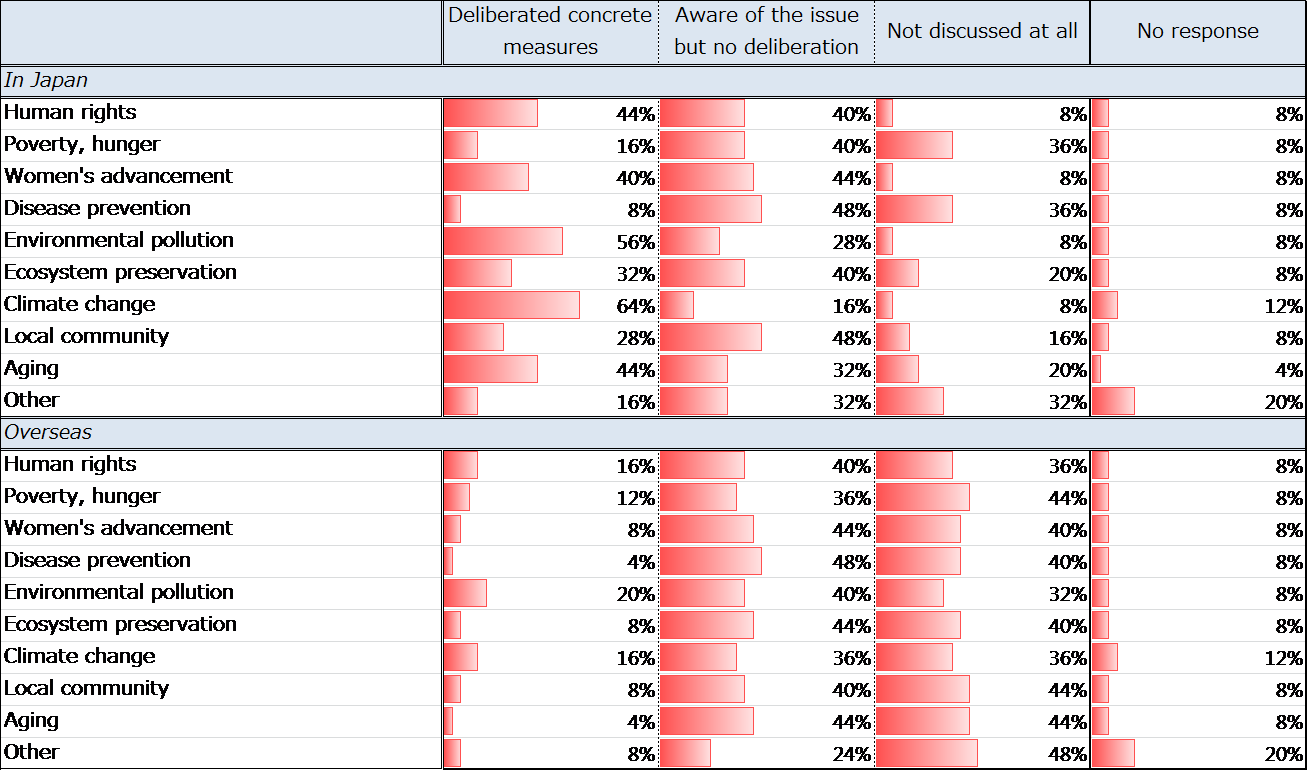

To what degree does the presence or absence of stakeholder dialogue affect a company’s involvement in social issues? In the latest survey, we asked respondents to choose one of three statements to characterize their level of interest in various social issues, in Japan and overseas. The choices were (1) we have deliberated concrete measures on more than one occasion; (2) we are aware of the issue but have not deliberated concrete measures; (3) we have not discussed it at all.

Figure 4 indicates the level of interest in each social issue among the group of 185 companies that reported engaging in stakeholder dialogue, while Figure 5 shows the results for the 18 companies that did not engage in such dialogue. Overall, companies that engaged in dialogue with stakeholders were more likely to report having reached the stage of concrete deliberations. Companies without dialogue were more likely to choose “we have not discussed it at all” or skip the question entirely.

Figure 4. Level of Interest in CSR Issues at Companies Engaging in Stakeholder Dialogue

Figure 5. Level of Interest in CSR Issues at Companies Not Engaging in Stakeholder Dialogue

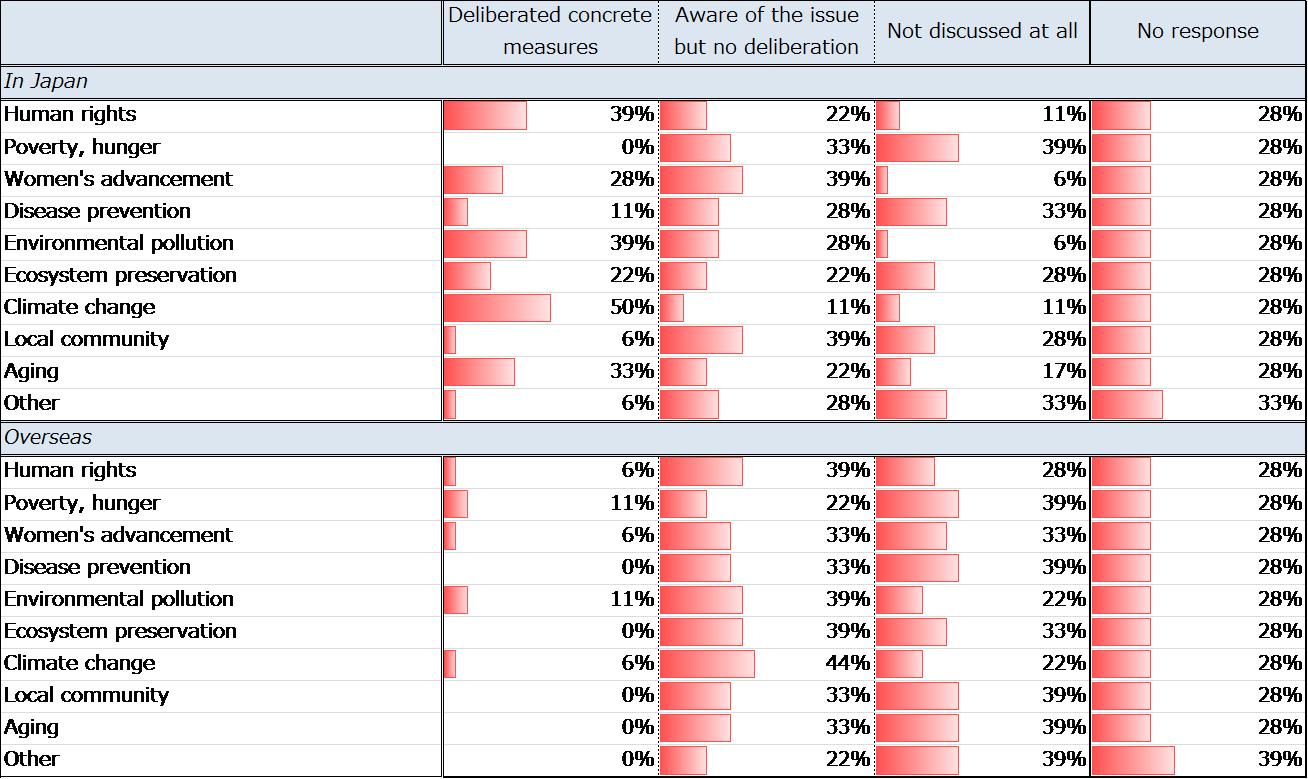

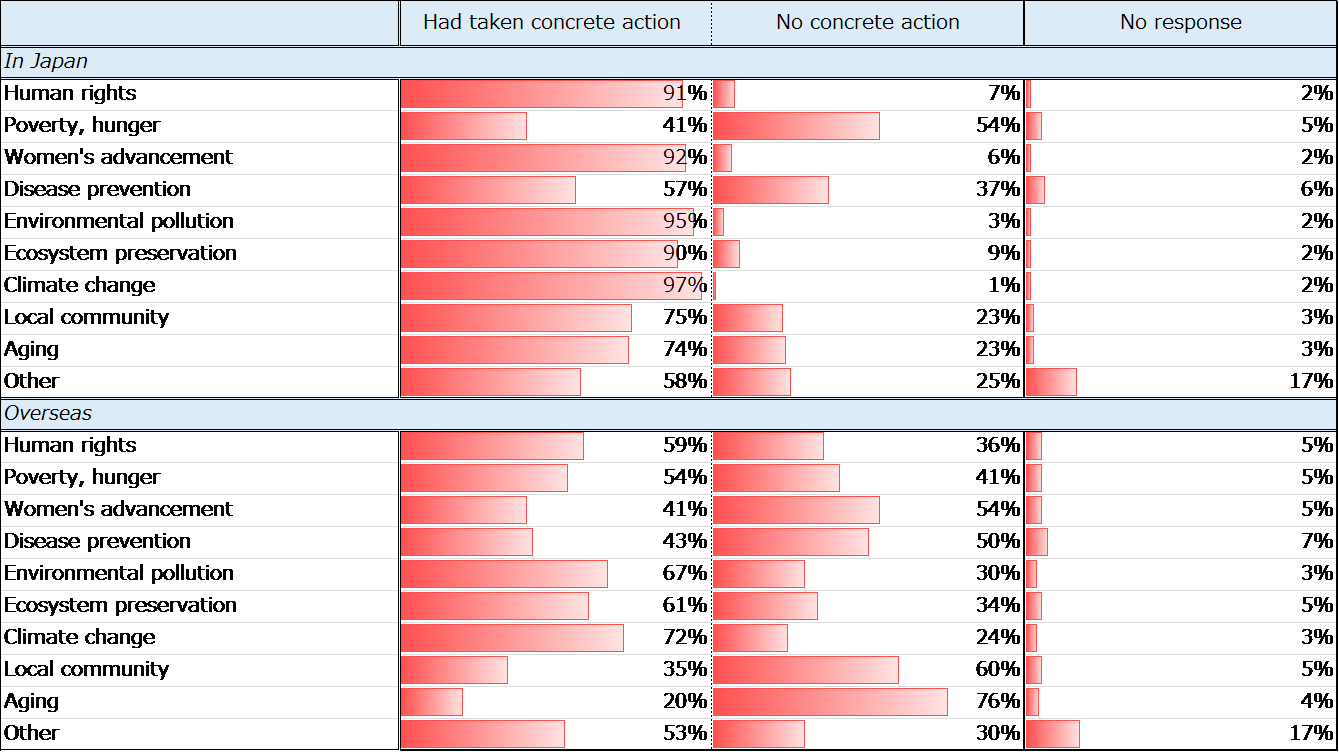

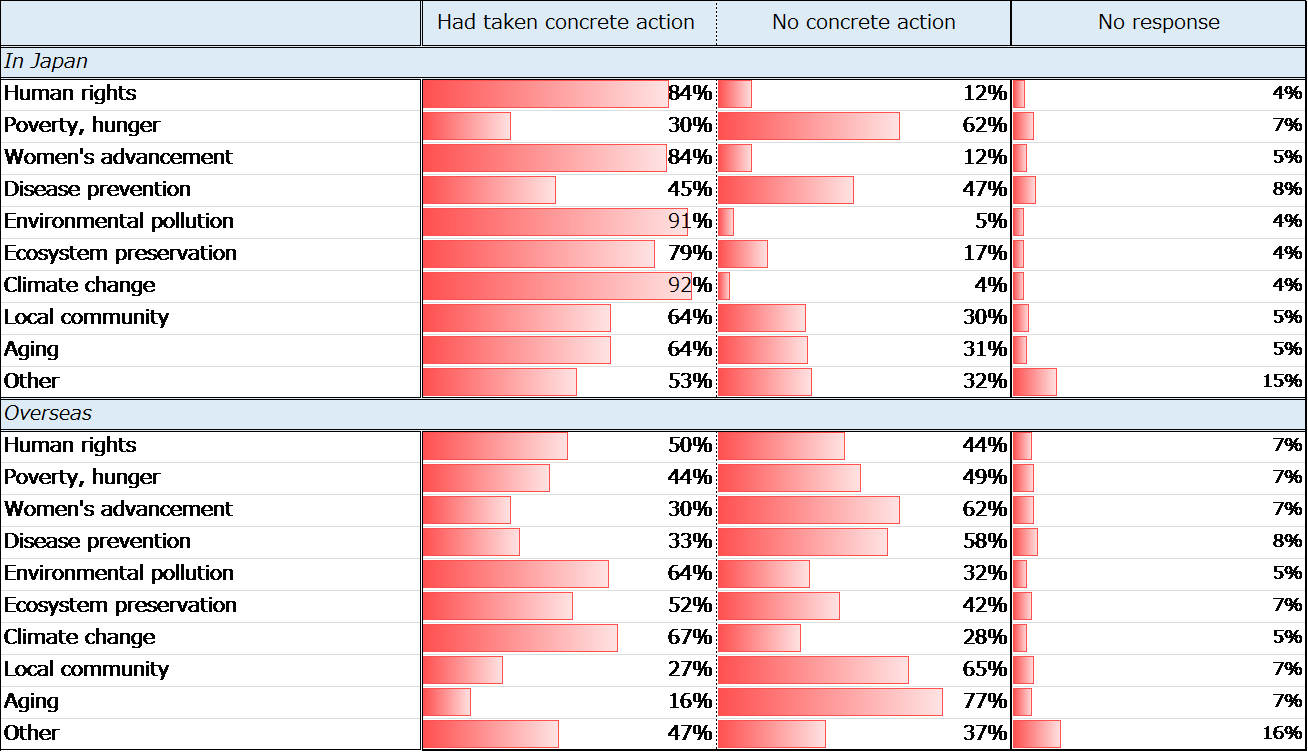

Next, let us look at the impact of stakeholder dialogue on actual implementation of CSR initiatives. The survey asked companies to indicate the basic social issues on which they had taken concrete action as a corporation, including programs initiated by the company, donations, and employee participation in external programs. The results for the companies engaged in stakeholder dialogue are seen in Figure 6, while those for companies without such dialogue are shown in Figure 7. Comparing the two, we see that the discrepancy widens at the implementation stage. The no-dialogue companies seem to have particular difficulty in transitioning from interest to concrete action. Moreover, with regard to overseas initiatives in certain issues (human rights, women’s advancement, climate change), action actually outpaced interest. This suggests a very passive decision-making process.

Figure 6. Implementation of CSR Initiatives at Companies Engaging in Stakeholder Dialogue

Figure 7. Implementation of CSR Initiatives at Companies Not Engaging in Stakeholder Dialogue

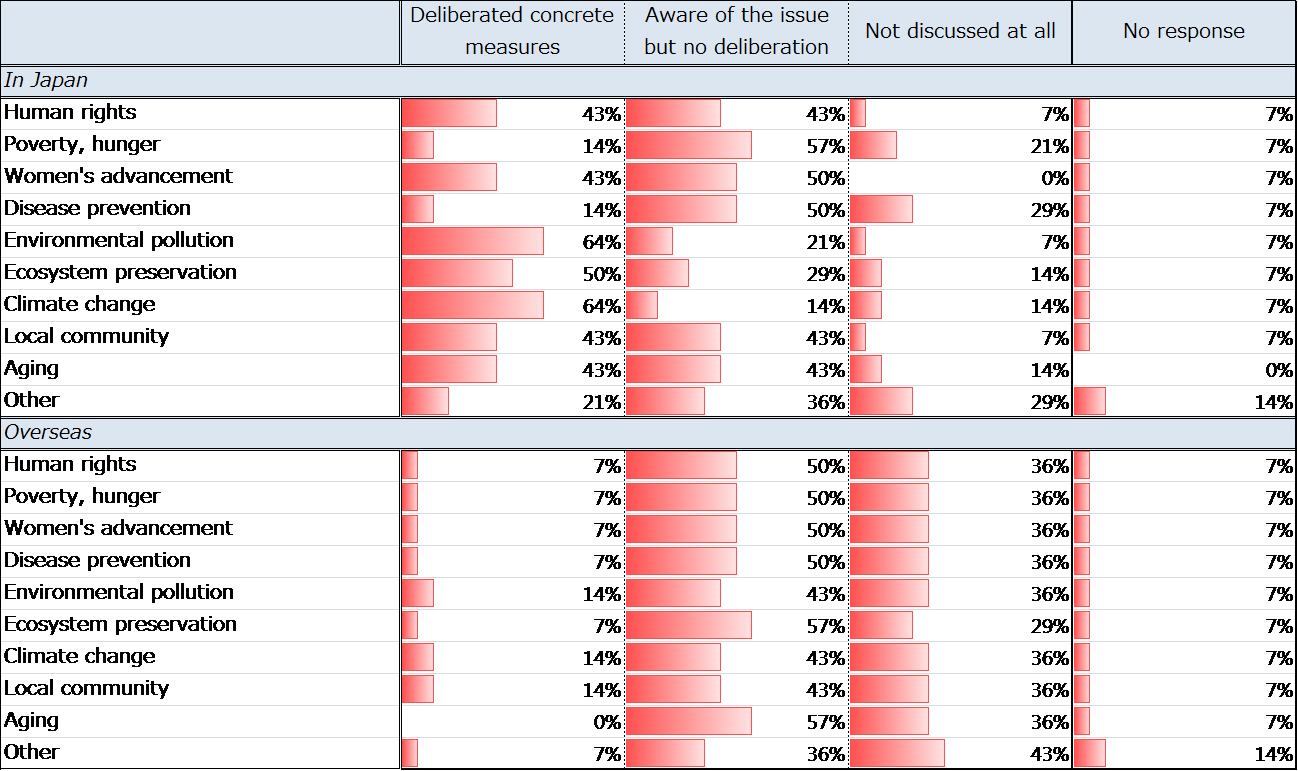

The survey also asked whether companies were engaged in “social dialogue,” defined as dialogue with NGOs, NPOs, and socially vulnerable groups. The questionnaire results indicated that 115 of the responding companies engaged in some form of social dialogue, while 87 did not. Given the relative parity in numbers (compared with the 10:1 ratio between companies engaged in some form of stakeholder dialogue and those reporting none), we wondered whether we would see any significant difference in outcomes between the two groups.

The results for level of interest in social issues are displayed in Figures 8 and 9. The social dialogue group reported a higher level of interest overall, with the gap between the two groups being particularly wide in overseas initiatives. A full 71% of the social dialogue group reported an active interest (concrete deliberations) in climate change at overseas affiliates, as compared with only 38% of the no-social-dialogue group, a difference of 33 points (a curious discrepancy, given that climate change is by nature a transnational issue). Engagement in social dialogue also correlated strongly with interest in the issue of poverty. These results appear to reflect the influence of NGOs and NPOs as partners in dialogue. Many of these organizations are active in developing countries, where poverty is a serious issue, or have links with overseas NGOs. Through dialogue, the groups have been able to communicate their concerns to Japanese companies.

Figure 8. Level of Interest in CSR Issues at Companies Engaging in Social Dialogue

Figure 9. Level of Interest in CSR Issues at Companies Not Engaging in Social Dialogue

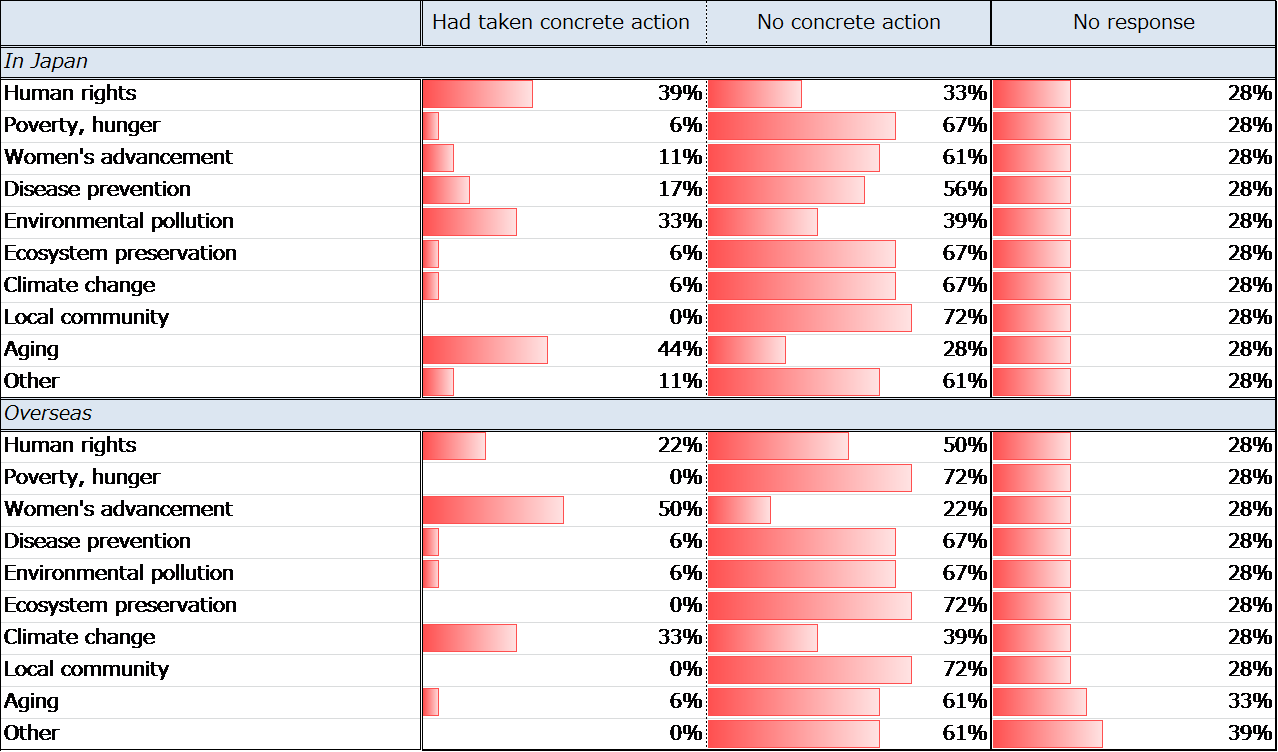

What about the impact on concrete action? As seen in Figures 10 and 11, engagement in social dialogue correlates strongly not only with companies’ interest in social issues but also with their implementation of concrete steps to address them. Here, again, we see a striking difference in the overseas responses, but companies engaged in social dialogue were significantly more likely to tackle human rights, poverty, and women’s advancement domestically as well. Where these issues are concerned, dialogue with socially vulnerable groups would seem to play an important role. A key challenge for Japanese businesses going forward would therefore be to overcome their disinclination and actively seek out dialogue with a variety of social groups.

Figure 10. Implementation of CSR Initiatives at Companies Engaging in Social Dialogue

Figure 11. Implementation of CSR Initiatives at Companies Not Engaging in Stakeholder Dialogue

C. Human Resources Development

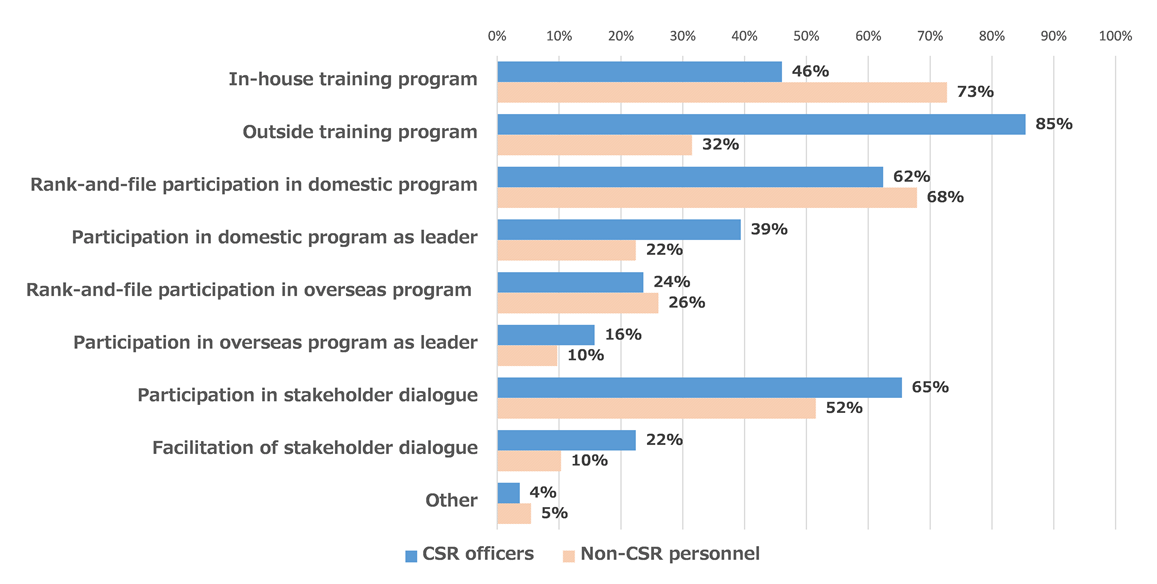

At a time of growing recognition of the importance of CSR in business management, many corporations are making efforts to equip their personnel with the knowledge and skills needed to address social issues. In our survey, 165 companiesーa full 80%ーreported engaging in some form of CSR training or education. We asked this group to identify the programs in which (1) CSR officers and (2) non-CSR, rank-and-file employees participated to shed light on the nature of their personnel policies (Figure 12).

Figure 12. CSR-Related Human Resources Development Programs

Out of the various categories of human resources development programs, three were most often directed toward CSR officers: participation in an outside training opportunity, participation in a domestic program in a leadership capacity, and participation in stakeholder dialogue. In-house training programs, rank-and-file participation in a domestic program, and rank-and-file participation in an overseas program were more often intended for non-CSR personnel. This suggests that, when it comes to personnel development, Japanese companies have gravitated toward a kind of standard model: sending CSR officers outside the company to gain experience and knowledge that they can bring back and share with other employees through in-house programs.

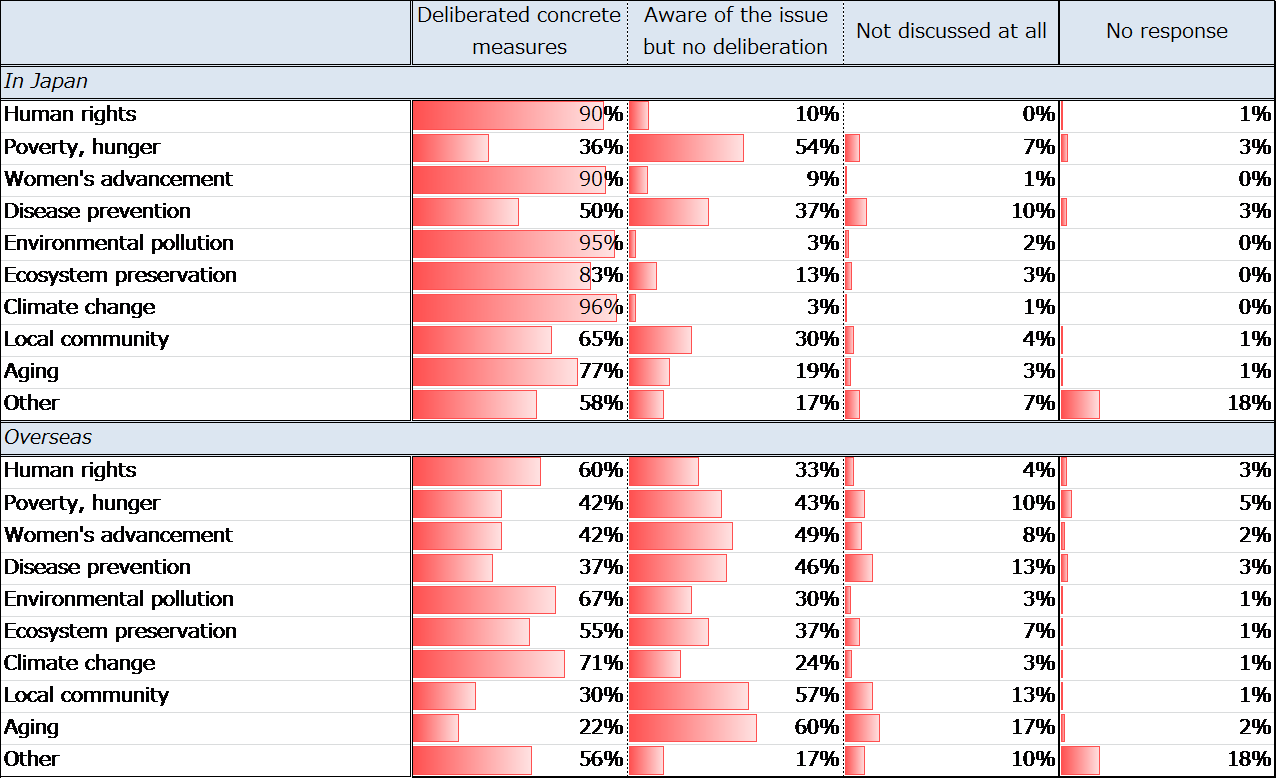

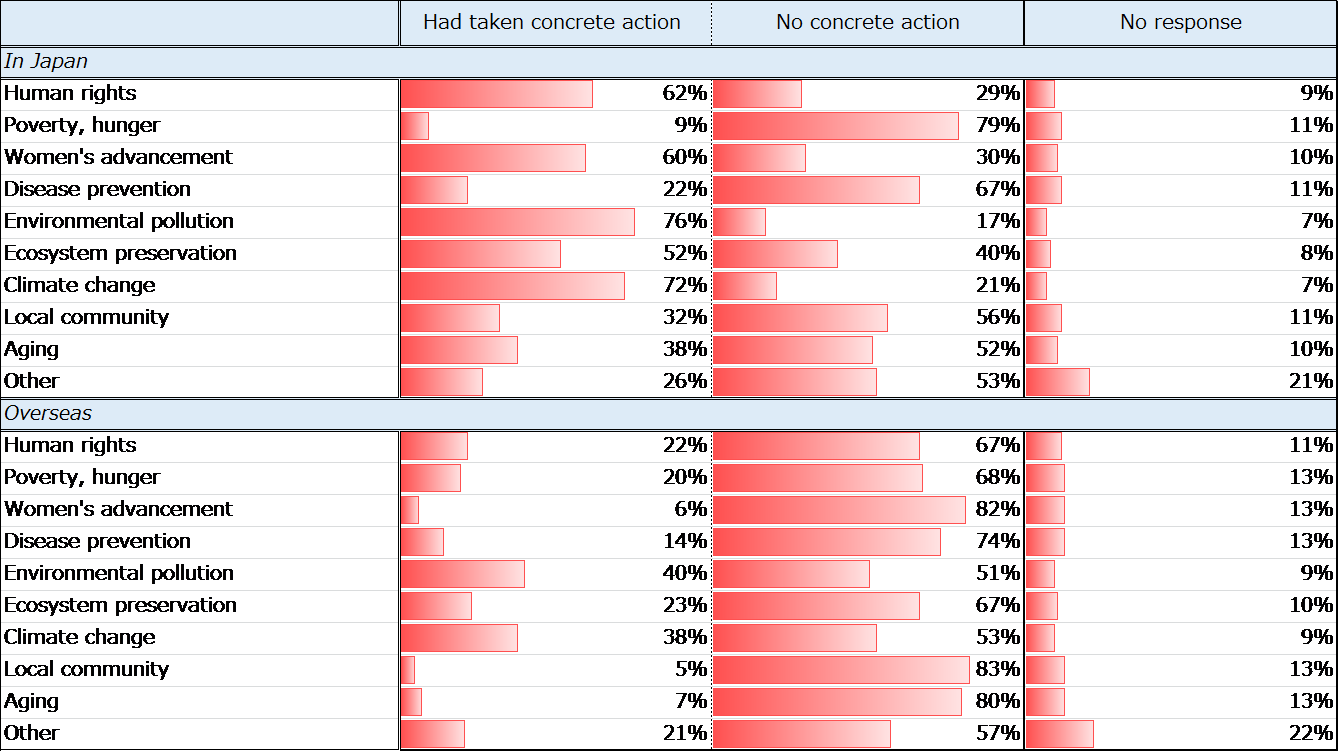

Now let us see how the presence or absence of such development programs correlates with interest in various social issues. Figures 13 and 14 show the interest levels among the 165 companies with CSR training programs and the 38 without, respectively. Comparing the two, we again see a conspicuous difference with regard to issues overseas. On the domestic side, by contrast, a large percentage of both groups reported having reached the stage of concrete deliberations on multiple social issues. This suggests that Japanese businesses have reached a relatively mature stage in terms of their awareness of domestic issues. The impact on interest in overseas and domestic issues was similar to that of social dialogue. The fact that CSR training often includes participation in external training programs and stakeholder dialogue may help account for the fact that human resources development and social dialogue exert a similar impact.

Figure 13. Level of Interest in Social Issues at Companies Engaging in CSR Training

Figure 14. Level of Interest in Social Issues at Companies Not Engaging in CSR Training

At the same time, the percentage of companies responding “we have not discussed it at all” was somewhat higher among companies with CSR training programs than among those engaged in social dialogue. The implication is that human resources development alone is not enough to induce interest in social issues. What should a company do if corporate commitment to social issues flags despite its efforts at CSR education? On the basis of our survey results, we might tentatively suggest a top-down strategy. It seems probable that a well-coordinated campaign combining top-down engagement by senior management with a bottom-up approach in the form of employee education could further boost the level of interest in social issues.

After all, while training and education can unquestionably help deepen understanding of social issues and instill a sense of urgency among individual workersーincluding those not assigned to a CSR departmentーturning that into an organizational commitment is a different matter, particularly in a company with 10,000 or more employees. This is why top-down efforts to build interest in social issues are indispensable. The results of our latest survey underscore the importance of a clear commitment to CSR at the highest level. It follows that a top-down commitment that is well coordinated with a bottom-up CSR training program should enhance the effect.

Next, let us consider the impact of human resources development programs on the implementation of concrete initiatives to address social issues (Figures 15 and 16).

Figure 15. Implementation of Social Issues at Companies Engaging in CSR Training

Figure 16. Implementation of Social Issues at Companies Not Engaging in CSR Training

When it comes to action on social issues, we see an interesting phenomenon. Even among the companies that have made no effort to educate employees about CSR, under virtually every issue heading, about 20% of respondents reported having taken action. We can posit two possible explanations for this.

One is that companies already have the high-caliber employees and systems that they need to put CSR into action without any special training or education. This seems an overly optimistic theory, given all we have learned from surveys and interviews about the difficulties companies face in cultivating CSR literacy and skills on an ongoing basis.

The other possibility is that many of these companies are approaching CSR as a series of isolated measures instead of a company-wide process of improvement. Depending on the kind of undertaking, it is simple enough for one individual to draw up a plan and carry it out without any special CSR training. Even a one-shot program or donation counts as concrete action. In any case, the fact that a surprising number of companies claim to be taking action on social issues without engaging in CSR training is not necessarily cause for rejoicing.

D. CSR Governance

In the latest survey, like those before it, we asked respondents to indicate whether their company had a specific department, dedicated or otherwise, in charge of CSR management (Figure 17). We found that more than 60% had set up dedicated departments, and another 30% had placed CSR under the purview of such key departments as public relations, corporate planning, or the office of the president. In Japan today, corporations with no formal CSR governance framework constitute a distinct minority.

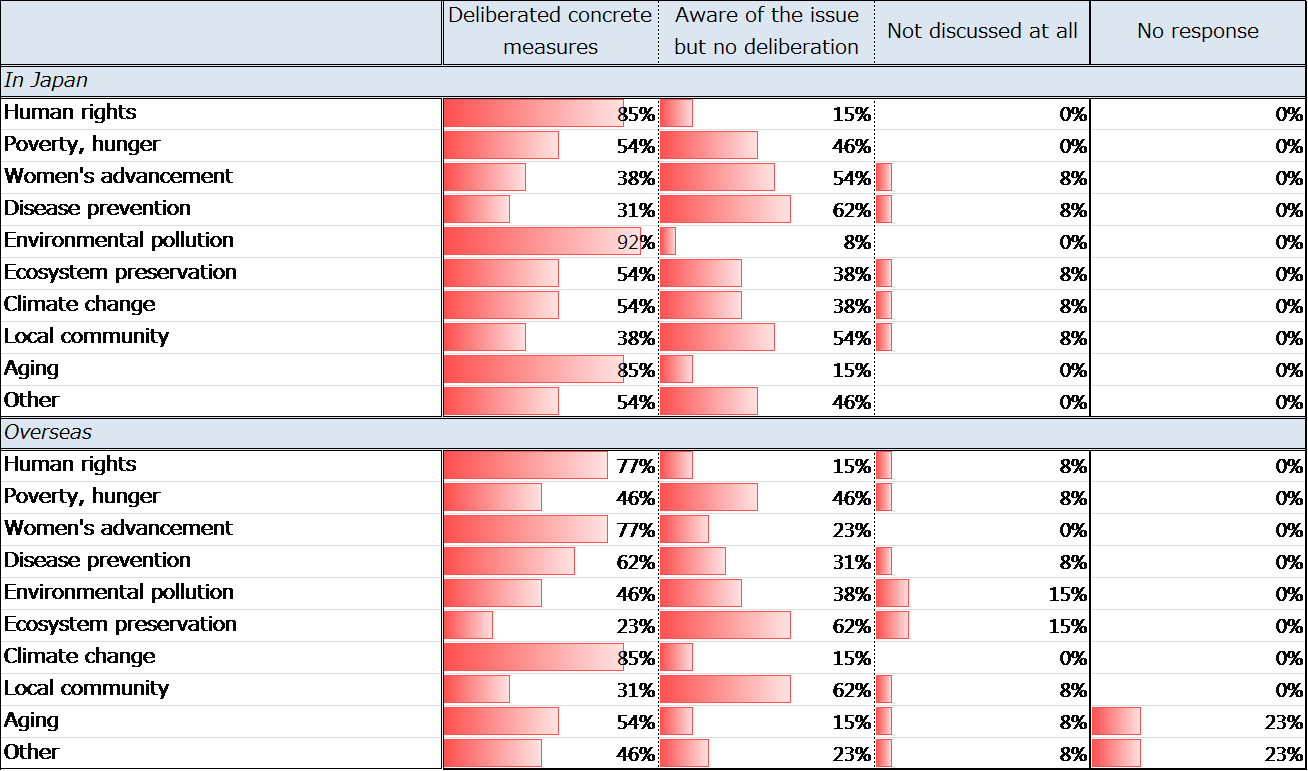

Figure 17. Department in Charge of CSR Management

We decided to compare companies at the opposite ends of the spectrum: on the one hand, the 130 with dedicated CSR departments; on the other hand, the 14 with no particular unit assigned to handle CSR (Figures 18 and 19). Generally speaking, the former group reported a higher level of interest in social issuesーparticularly overseasーthan the latter. However, this organizational factor seemed to have little impact on whether a company had progressed to the stage of concrete deliberations; in both groups, companies were most apt to respond that they were aware of an issue but had not begun concrete deliberations. Compared with a factor like stakeholder dialogue, the presence or absence of a CSR department was a weak predictor of a company’s progress to the stage of concrete deliberations.

Figure 18. Level of Interest in Social Issues at Companies with Dedicated CSR Departments

Figure 19. Level of Interest in Social Issues at Companies without CSR Department

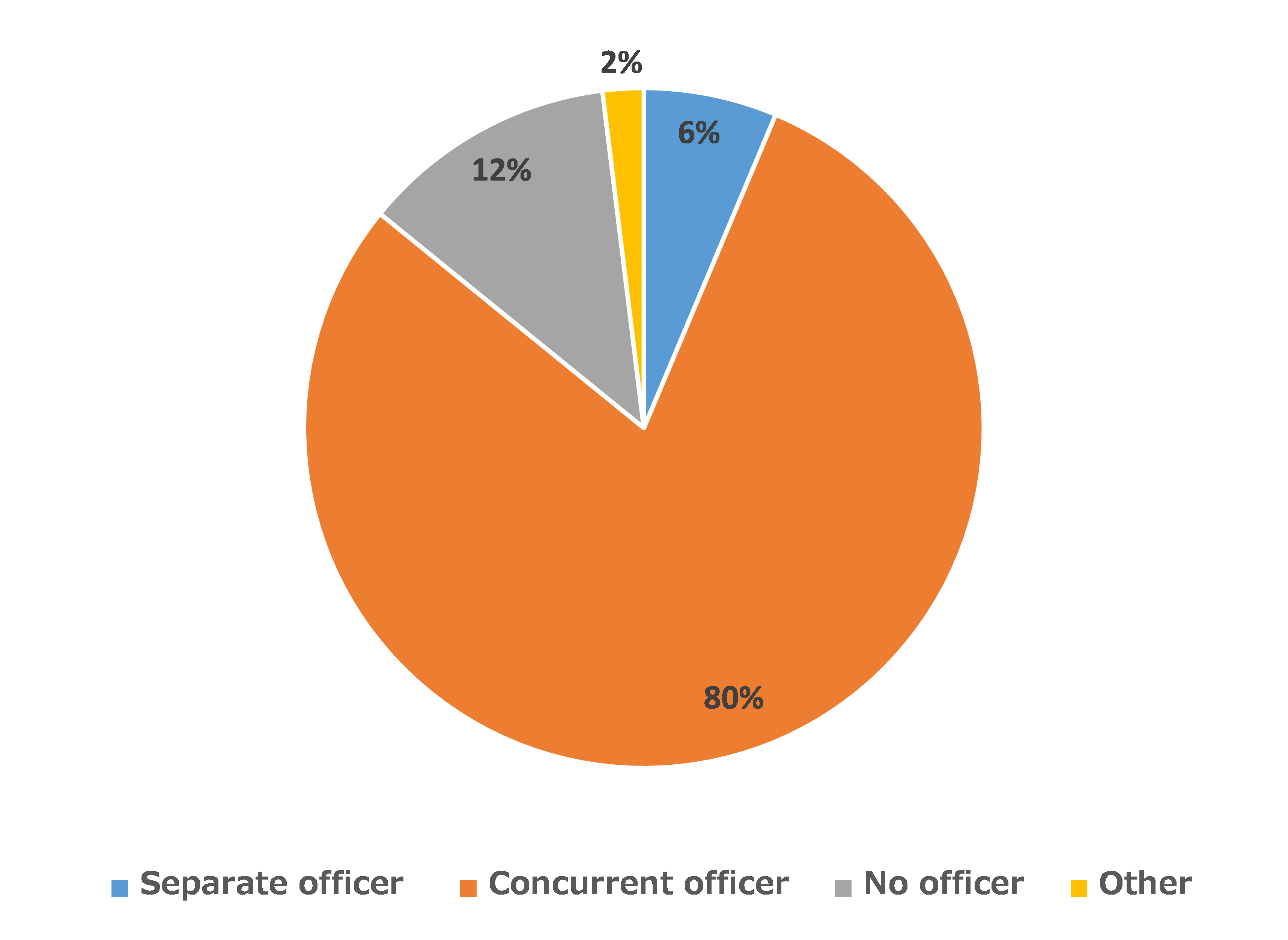

Let us now turn to another prominent indicator of CSR governance, that is, whether a company has a separate executive position in charge of CSR, such as chief sustainability officer (Figure 20). The latest survey revealed that only a small portion of Japanese companies have such posts, even though the majority have CSR departments. This suggests that few Japanese companies regard CSR as a management issue requiring the judgment of a senior executive with specialized knowledge of CSR. The majority see it, rather, as something to be planned and implemented by a CSR department or section.

Figure 20. Companies with Executive CSR Officer

We looked at the responses of the 13 companies that reported having an executive post devoted exclusively to CSR and compared them with the 25 companies in which no senior executive was in charge of CSR (Figures 21 and 22). Both groups were fairly small. The results suggest that the impact of this factor on interest levels is comparable to that of the presence or absence of a CSR department. In both groups, a high percentage of respondents said that they were aware of social issues but had not begun concrete deliberations.

Figure 21. Level of Interest in Social Issues at Companies with CSR Officer

Figure 22. Level of Interest in Social Issues at Companies without CSR Officer

It appears that the creation of dedicated CSR governance organs is not particularly instrumental in getting companies over the hump between awareness and action. Of course, there is no reason to suppose that the presence of a CSR department or a chief CSR officer has a negative impact. But neither is there evidence that the presence of such entities automatically leads to a more active involvement in social issues. It seems fair to say that such an organizational framework is not in itself a CSR game changer.

E. How Social Issues Are Brought to Companies’ Attention

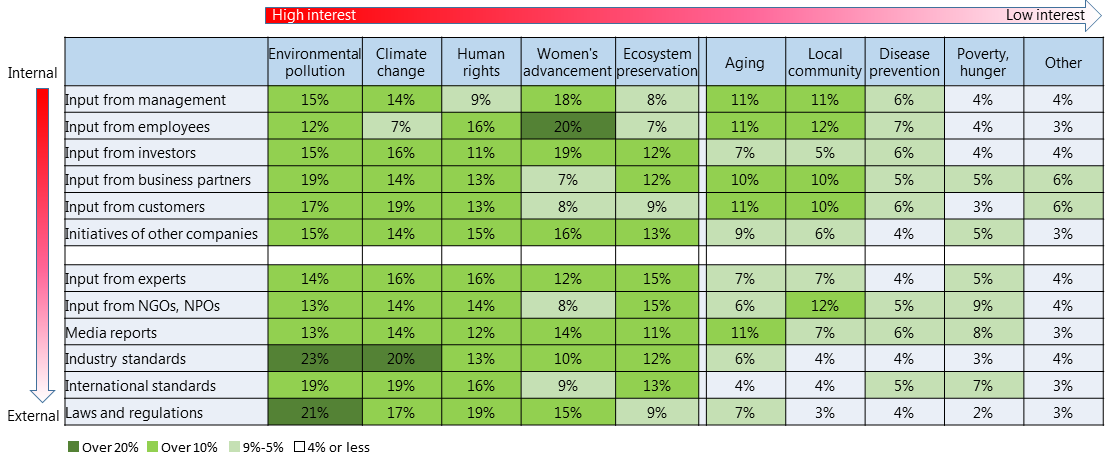

In our latest survey, we asked respondents for the first time how different social issues came to their attention. Companies, of course, are organizations, and as such have access to internal input in the form of feedback from employees, as well as to external sources like legal and regulatory information and media reports. We felt that by identifying the process by which Japanese companies developed an interest in CSR, we could better assess their level of sensitivity to social issues. Further, if the process varied significantly by issue category, that information could offer clues as to ways of enhancing corporate sensitivity and responsiveness in general.

In Figure 23, social issues (domestic and overseas combined) are arranged from left to right in descending order of the interest level indicated by our respondents on average. We can see that, generally speaking, Japanese companies have the highest level of interest in such environmental issues as pollution and climate change and the lowest level of interest in disease and poverty. Different catalysts are ranked from top to bottom, beginning with the most internal (input from employees and top management) and ending with the most external (laws and international standards). The number in each cell represents the percentage of responses that linked the catalyst to the left with the problem at the head of the column. The shading of the cells is keyed to that percentage, with the darkest shading representing the highest ratio.

Figure 23. How Social Issues Came to Companies’ Attention

As we can see, the strongest linkages are between (1) women’s advancement and input from women employees, (2) environmental pollution and industry standards, (3) climate change and industry standards, and (4) environmental pollution and laws.

These results tell us, first of all, that the voices of women employees are beginning to be heard within the Japanese corporation, and second of all, that companies rely more heavily on external information and legal directives for guidance on environmental and climate-change issues. We also found that an internal impetus was more likely to be cited in relation to aging and community-engagement issues.

Overall, our data indicate that internal information and input tend to provide the impetus for concern over local issues, while external information plays a dominant role in raising companies’ awareness of global issues. Thus while internal communication appears to be improving and having a positive impact on CSR overall, we can see that it is still quite unusual for Japanese companies to target global issues voluntarily, on their own initiative. The challenge going forward is to pursue more active dialogue with stakeholders inside and outside the company in order to widen their field of vision.

What are the implications of these findings for public policy? As one can gather from Figure 23, laws and regulations and industry standards can be very effective in alerting companies to social issues. At the same time, relatively few companies are made aware of problems relating to the local community, disease, or poverty through those channels. It seems likely that more intervention on the public-policy level could encourage involvement in those issues and promote further corporate action on the environment as well. That said, excessive administrative interference has the potential to turn CSR into an extension of government policy and stifle private-sector innovation and initiative. The optimum balance between public policy and private-sector initiative is a topic for ongoing discussion.

F. Self-Assessment of CSR

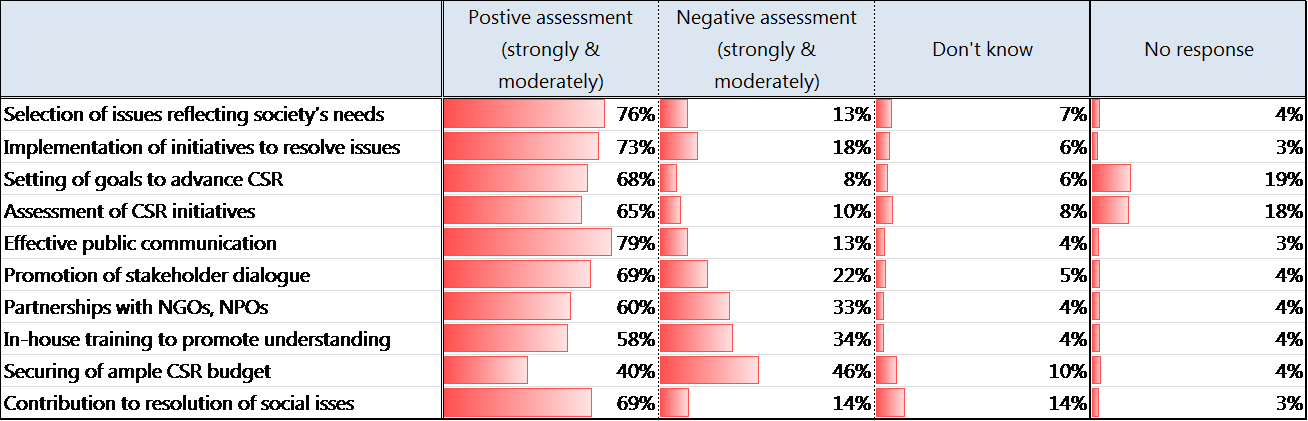

How do Japanese businesses assess their own CSR efforts? In our latest survey we decided to ask companies to rate specific aspects of their CSR programs, as opposed to reporting their overall level of satisfaction (Figure 24).

Figure 24. Self-Assessment of CSR

Generally speaking, respondents were apt to rate themselves most highly in respect to the selection of social issues to address as a company, implementation of CSR initiatives to address those issues, and external communication to inform the public of those initiatives. This indicates an awareness of the key stages in the CSR process. Still, a full 13% of respondents gave their own companies a negative rating on the first stage in the cycle, “selection of issues reflecting society’s needs.” What this tells us is that, for whatever reason, a substantial number of companies are selecting issues that are out of synch with society’s needs. The reasons no doubt vary by company. But a stumble at this crucial stage calls into question the value of the company’s entire CSR program. Clearly, this is an important area for improvement.

CSR budget was the one area in which self-assessment was more often negative than positive. The majority of respondents, we can surmise, feel that they could make more progress on CSR if they had more money to spend on it. No doubt many CSR officers share this belief. Yet when we look at the responses in conjunction with other information from the survey, we find little consistency between satisfaction with the CSR budget and the actual amount allocated. Some respondents expressed dissatisfaction with CSR budgets amounting to hundreds of millions of yen, while others gave their companies high ratings for relatively meager budgets. In any case, no company has unlimited resources to devote to CSR. With this in mind, the allocation and use of funds for CSR should be a matter for company-wide discussion and deliberation.

G. Conclusions

Finally, let us summarize the findings of our latest CSR survey with respect to the efficacy of various tools and strategies in jump-starting corporate action to address social issues.

First, we looked at involvement by top management. The results of our survey revealed that companies are more likely to have an active and effective CSR program when top management is routinely exposed to information about it. Companies develop fruitful CSR programs when CSR issues come up at meetings of the board and other top-level governance bodies, where senior executives can get briefed and exchange ideas about issues and solutions. Poor CSR performance is frequently blamed on “a lack of commitment at the top,” and this may be valid as far as it goes. But such criticism is too abstract to be useful. Top-level commitment is unlikely to materialize out of a vacuum. Companies need to systematically create opportunities for information sharing and discussion in order to elicit a commitment from top management. This is one of the key roles of CSR departments and officers.

The next factor was dialogue. In this survey, we examined both stakeholder dialogue in the narrow sense and social dialogue. The results highlighted the effectiveness of dialogueーand social dialogue in particularーas a tool for identifying social issues. We found that companies that engage in dialogue with NGOs, NPOs, and the socially vulnerable tend to be particularly sensitive to social issues and proactive in taking steps to address them. However, the percentage of companies engaging in social dialogue is still not very high, perhaps because NGOs, NPOs, and advocates for the socially vulnerable are apt to be fairly blunt in their criticism of corporate policies. Clearly, efforts to expand and enhance social dialogue should be high on the CSR agenda.

A pioneer and exemplar in this area is Marks and Spencer, which has premised its CSR strategy, Plan A, on engagement with a wide range of external stakeholders. [1] In an effort to enhance its capacity for grappling with social issues, M&S has skillfully used its many and varied CSR activities to create opportunities for stakeholder dialogue on an equal footing. In the process, it has developed a natural and comfortable mode of interaction with NGOs and NPOs, paving the way for productive partnerships. Through dialogue, we get to know others, and in getting to know them, we build trust. That relationship of trust becomes the foundation for collaboration. This is the ultimate purpose of stakeholder dialogue.

The third factor was human resources development. The survey results brought into focus a kind of standard Japanese model for CSR training, in which CSR officers are sent outside the company to acquire knowledge and skills that they then pass on to their colleagues. From the standpoint of the efficient division of labor, it seems natural for companies to gravitate toward this model, and it has been effective up to a point. The danger, however, is that employees outside the CSR department will tend to take a rather detached, academic view of social problems. Further progress may hinge on companies’ ability to build a system that enlists the commitment of top management in the development of company-wide CSR literacy, skills, and leadership.

Fancl Corp. is a shining example of a business that has put human resources development at the center of its CSR policy. [2] Fancl is working to foster a genuine sense of social responsibility among its employees through programs in which they volunteer to lead personal grooming workshops at facilities for the disabled. Fancl’s people-oriented CSR approach is apparent not only in these externally focused programs but also in its own dedication to workforce diversity. Through its special subsidiary Fancl Smile, it is actively recruiting individuals with disabilities and developing inclusive work arrangements and employee training programs.

Another exemplar in the area of human resources is German-based software company SAP. [3] By integrating CSR training into its leadership development for management-track employees, it is hoping to build CSR awareness into management from the outset. This may be one answer to the dilemma of CSR training for senior managers, who are often too preoccupied with day-to-day duties to set aside time for anything else. Like SAP, many Japanese corporations provide separate personnel training programs for management candidates. It should be possible for them to adapt SAP’s model and instill a commitment to CSR among its managers from the start through long-range training spanning 10 or even 20 years. It will be interesting to see whether Japanese businesses can develop comprehensive, integrated personnel development strategies of this sort.

The final factor examined was CSR governance. The results of this year’s survey were essentially the same as those obtained the previous year. Many Japanese companies now have departments and executives dedicated to CSR. So far, however, we have little evidence that such organizational measures have contributed substantially either to the level of interest in social issues or to the quantity and quality of corporate efforts to address them. We can infer from these results that CSR efforts can move forward without the benefit of dedicated CSR departments or executive posts. Although governance is an important aspect of CSR, the creation of dedicated organs should be secondary to the larger task of fostering social awareness and commitment at every level of the organization.

This principle is aptly illustrated by the achievements of certain pioneering small and medium-sized companies. Large corporations, with their abundance of human and financial resources, are at an obvious advantage when it comes to creating a CSR governance framework. Yet even without such resources, small and medium-sized companies can achieve impressive results in the area of CSR, as two case studies in this year’s report demonstrate. [4] Conscious of the limits of their own resources, these companies have pursued a variety of strategies to supplement and maximize their capacity to effect change. The large corporations that form the bulk of our survey sample could learn something from these modest businesses’ dedication and determination to make a difference.

There is no single game changer capable of transforming companies into active and effective agents for the resolution of social problems. A multifaceted approach is vital, especially since the factors we examined are closely interrelated.

Of course, companies vary widely in many respects, from the markets they serve to their organizational structure and financial, technical, and human resources. Even so, every business has the capacity to contribute to the resolution of social problems. At a time when corporate social responsibility has become a matter of common sense, private businesses face closer scrutiny and higher expectations than ever before. To meet public expectations, each company must continuously review its own goals, objectives, and strategies for contributing to the creation of a sustainable society.

[1] See Mikiko Fujiwara, “From Dialogue to Partnership: Marks & Spencer,” in CSR White Paper 2015, https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=416 .

[2] See Zentaro Kamei, “Rebuilding CSR around Human Resources: Fancl Corp.," in CSR White Paper 2015, https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=261 .

[3] See Mikiko Fujiwara, “Social Sabbatical Program Combines CSR and Leadership Development: SAP,” in CSR White Paper 2015, https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=442 .

[4] See Makoya Kageyama, “CSR Challenges and Strategies for Small Businesses,” https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=456 , and Zentaro Kamei, “A Small but Socially Responsive Company: Soken,” https://www.tkfd.or.jp/en/research/detail.php?id=454 .