- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

Corporate Responsibility in the Age of the SDGs: Role of the Keidanren Charter in the Evolution of CSR in Japan

January 15, 2019

The development of CSR in Japan has been largely business-led, and the pivotal role played by Keidanren can be clearly seen in the evolution of the Keidanren Charter of Corporate Behavior, formulated and adopted by the business community to promote good citizenship among Japanese companies.

* * *

Background

A distinguishing feature of CSR in Japan is the fact that its development has been largely business-led. In Europe, widely considered the world leader in CSR, the impetus came from a spate of new laws and policies (such as the European Union’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive), along with campaigns by nonprofit groups and negative screening by investors. But Japanese companies have faced relatively little outside pressure domestically. The main impetus for CSR in Japan arose from a growing awareness among multinational businesses of the need to stay abreast of global CSR trends to compete internationally. It is no accident that the pioneers of social responsibility in Japan were electronics firms, which easily perceived the need to comply with the EU’s CSR standards in order to do business in the European market. Indeed, many people trace the dawn of CSR in Japan to 2003, when Ricoh and Sony established Japan’s first corporate departments expressly dedicated to CSR.

This background explains the pivotal role played by Japan’s best-known and most influential industry group, Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), in the development of CSR in Japan. That role is most clearly seen in the evolution of the Keidanren Charter of Corporate Behavior, the code of conduct formulated and adopted by the business community itself to promote good citizenship among Japanese companies.

The Charter of Corporate Behavior was first drawn up in 1991 in the wake of a series of scandals that had shaken the Japanese finance industry. This was a seminal period, during which Keidanren laid the foundations for CSR through such initiatives as the adoption of the Global Environment Charter (1991), with its basic call to “respect human dignity and work to build a society that achieves the goals of environmental conservation”; the establishment of the Council for Better Corporate Citizenship (1989); the launch of the philanthropic One-Percent Club (1990); and the establishment of the Keidanren Nature Conservation Fund (1992). All in all, Keidanren was well ahead of the curve when it came to promoting corporate citizenship.

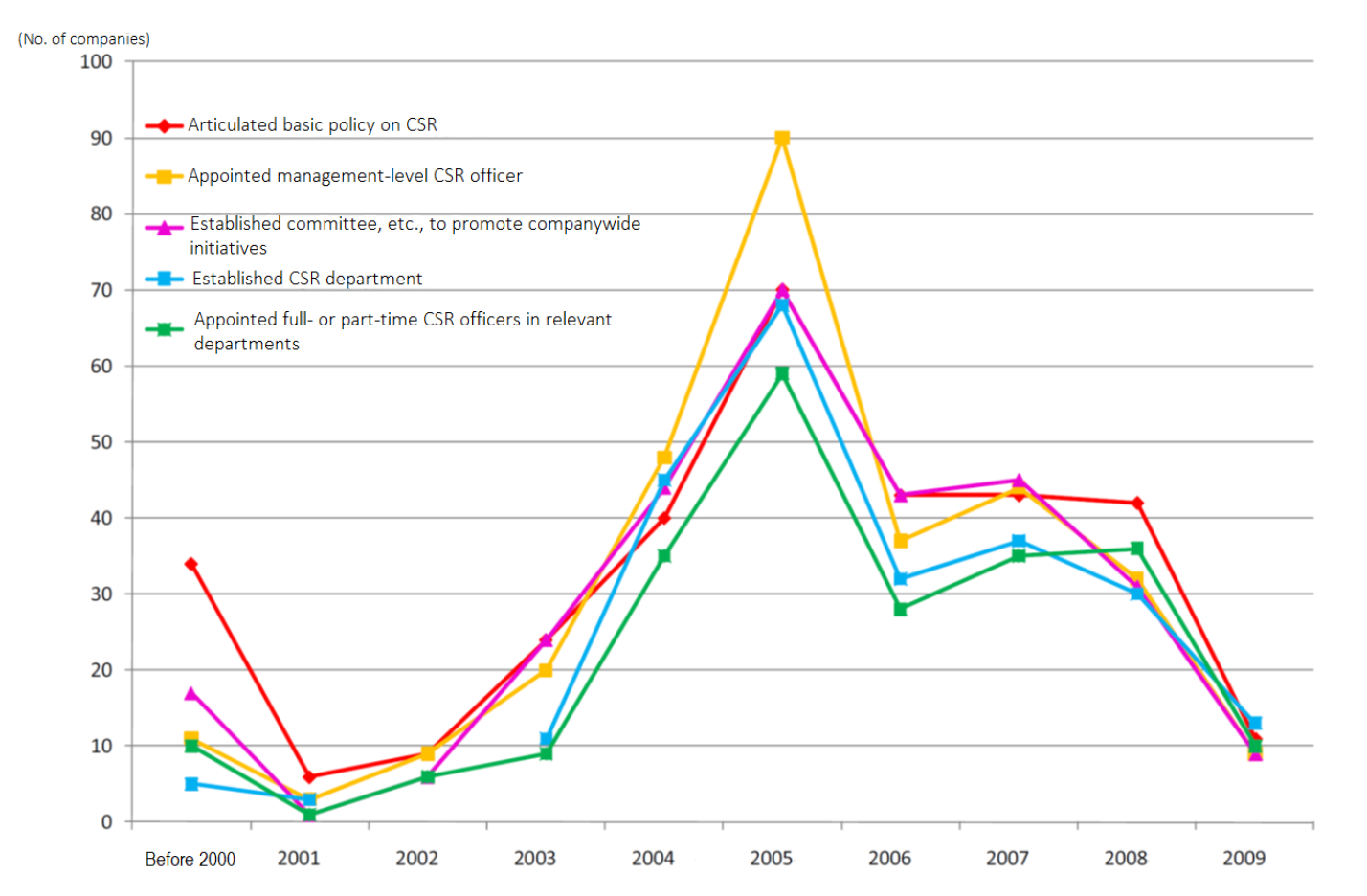

Figure 1. Year of Implementation of Initiatives to Promote CSR

Source: Keidanren, CSR Survey 2009.

Globally, the emergence of CSR as an influential concept dates to the beginning of this century. Indeed, it was in 2000 that the term CSR was incorporated in the Council of Europe’s Lisbon Strategy, the United Nations launched the Global Compact, and the Global Reporting Initiative published its first set of guidelines for CSR reporting.

In the succeeding years, Japanese industry made rapid headway creating frameworks for CSR management through the establishment of CSR policies, departments, officers, and governance systems. According to Keidanren’s annual survey (Figure 1), this sort of activity peaked around 2005, in the wake of the 2004 revision of the Keidanren Charter of Corporate Behavior. In the following, I would like to review the ways in which this groundbreaking document and its successors contributed to the development of CSR in Japan.

From Code of Ethics to CSR Charter (2004)

In 2001, when domestic interest in CSR was still limited to a handful of forward-looking Japanese firms, the International Standards Organization (specifically, its Committee on Consumer Policy, or COPOLCO) began looking at the idea of drawing up a standard for social responsibility. In Japan, which has always taken international standards very seriously, the government and Keidanren established deliberative bodies to formulate a response.

In 2003, Keidanren’s Council for Better Corporate Citizenship (CBCC), which was charged with studying best CSR practices overseas and promoting them domestically, sent a mission to Europe and the United States to gauge how leaders in industry and the CSR community were responding to the ISO’s initiative. They encountered a somewhat more measured response in the West, where the move toward standardization was viewed as just one manifestation of the global trend toward CSR. One important lesson they took away was that businesses needed to invest in CSR for its own sake, regardless of whether the ISO standards ever materialized.

After the mission returned to Japan, Keidanren adopted a basic three-point policy emphasizing (1) the need for active promotion of CSR, (2) a focus on voluntary business-driven (not government-imposed) initiatives, and (3) a major revision of the Charter of Corporate Behavior to serve as a set of CSR guidelines for Japanese business. (I was personally involved in both the CBCC mission and the 2004 revision of the Charter of Corporate Behavior.)

In 2004, Keidanren established a task force to deliberate and draft a new version of the charter, which was released the same year. Unlike previous versions, which focused on business ethics, this one clearly reflected the rise of CSR as a global trend. The foreword provided an introduction to CSR, including its basic components and the circumstances behind the new global emphasis on socially responsible management.

The key points of the revision can be summarized as follows.

Sustainability: In the preamble, the 2004 charter calls on corporations to work voluntarily “toward the creation of a sustainable society” as social entities responsible for making a positive public contribution.

Human rights: The preamble also calls on companies to “respect human rights.” (However, at this point neither the body of the charter nor the implementation guidelines provide any further clarification.)

Supply chain management: Principle 2 of the revised charter calls for “fair business practices,” and principle 9 calls on top management to “raise awareness in their corporation and inform their group companies and business partners of their responsibility” to uphold the spirit of the charter.

Communication with stakeholders: The foreword to the charter identifies dialogue with stakeholders as one of the socially responsible behaviors expected of companies. The outline of the implementation guidelines for principle 3 calls on companies to “promote communication with shareholders and investors,” “disclose corporate information to stakeholders in an appropriate and timely manner,” and “promote two-way communication with society.”

In this way, the 2004 revision of the Charter of Corporate Behavior, anticipating the adoption of international standards for social responsibility, introduced and incorporated concepts regarded as central to the global conversation about social responsibility, thereby taking on the character of a CSR code for Japanese industry. It also clearly articulated Keidanren’s commitment to promote and guide the development of CSR in Japan, primarily through the charter and the associated implementation guidance document.

Alignment with ISO 26000 (2010)

The ISO eventually resolved the debate over the standardization of CSR by opting to formulate a “guidance” standard on social responsibility, ISO 26000, designed for use not just by businesses but by organizations of all kinds.

Keidanren moved quickly to involve itself directly in the drafting process via the ISO Working Group on Social Responsibility, or WG SR. It sent experts of its own (including the author) to participate in meetings, using the “black-pen approach” of submitting its own proposals, as opposed to the “red-pencil” approach of tweaking drafts submitted by others. It also established its own ISO 26000 task force to formulate proposals and other strategies for contributing to the process.

WG SR was the first ISO working group to adopt a multi-stakeholder process, and the deliberations were lengthy, continuing from 2005 to 2010. In the initial stages, before there was even a consensus on the basic concept of CSR, there seemed little prospect of agreement. The Japanese business community took the initiative early on by submitting its own complete draft. This helped immensely to advance the deliberations by giving members an overall picture of the finished standard and providing the basis for more grounded discussion. In its organization and even its wording, ISO 26000 incorporates many elements of the proposal submitted by Japanese industry. The role of Japanese business in the drafting of ISO 26000 can be regarded as a model of active and effective involvement in the development of international rules and norms.

ISO 26000 was the first international instrument dealing with social responsibility in a comprehensive fashion—defining the term, outlining its principles, and explaining how those principles should be put into action. Some 400 experts participated directly in the drafting process, including numerous representatives from developing countries and emerging markets. Since then, ISO 26000 has had a major impact on the development of national standards and has played a huge role in the spread of CSR principles and practices in industrial and developing countries alike.

ISO 26000 was released in 2010, and Keidanren revised its Charter of Corporate Behavior the same year to align it with the global standard. The revision affected every section of the charter and its implementation guidelines, but special mention should be made of the new emphasis on international norms and stakeholder engagement.

The revised principle 8 reads, “In line with the globalization of business activities, . . . respect human rights and other international norms of behavior. Also, conduct business by taking into consideration . . . the interests of stakeholders.” Meanwhile, the implementation guidelines expand on the concept of engagement and collaboration with stakeholders for the resolution of social issues, incorporating various ideas included in Japanese industry’s suggestions for ISO 26000.

Keidanren also took its international outreach to the next level on this occasion, providing an English translation (published on its website) not only of the main body of the charter but of the implementation guidelines as well.

The 2010 version of the Charter of Corporate Behavior and its implementation guidelines helped promote broad awareness and acceptance of ISO 26000 in Japan. It fostered a coherent understanding of social responsibility as a standard on which the international community had reached agreement and helped clarify the scope of CSR, a matter on which opinion still ranged widely.

Integrating the SDGs into Business Management (2017)

Over the next five years, the concept of CSR continued to evolve. I had the honor of chairing the task force charged with updating the Charter of Corporate Behavior with such changes in mind. The latest version of the charter, adopted in 2017, reflects important developments in the global evolution of CSR, as embodied in three international instruments approved by the United Nations: the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011); the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including the Sustainable Development Goals (2015); and the Paris Agreement on climate change (2015). Of these, the sweeping 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—which incorporate the basic principles of the other two documents—emerged as the main theme of the revision.

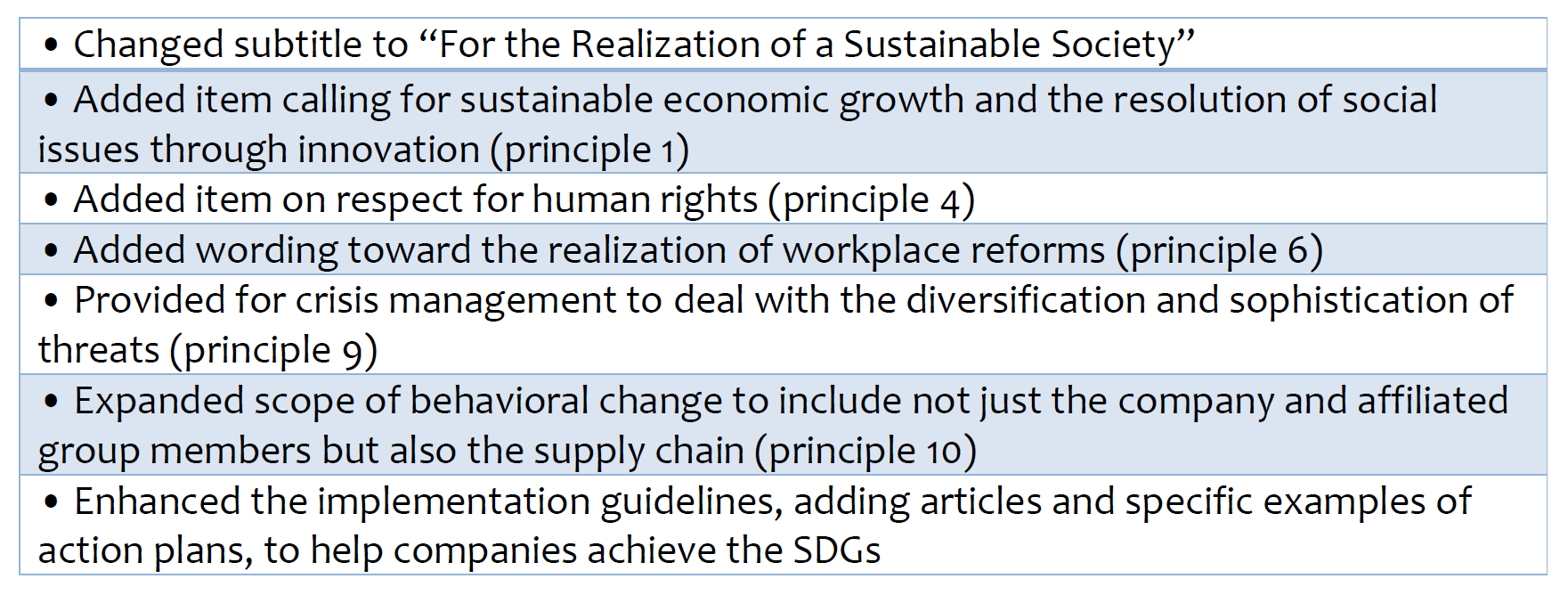

The most important features distinguishing the 2017 revision of the charter can be summed up as follows (see table):

• A call for private-sector innovation to achieve sustainable economic growth while addressing social issues (principle 1); as a central means to this end, a call for efforts to deliver on the SDGs through the development of an ultrasmart, people-centered society, or Society 5.0.

• Inclusion of the concept of human rights as one of the charter’s 10 principles (principle 4) and inclusion of specific examples, aligned with international norms, in the implementation guidelines.

Table. Major Revisions to the Keidanren Charter of Corporate Behavior (2017)

Business and Social Transformation

Another highly significant aspect of the 2017 revision was the change in the document’s subtitle, from “For Gaining Public Trust and Rapport” to “For the Realization of a Sustainable Society.” The idea of contributing to the development of a sustainable society was incorporated in the Charter of Corporate Behavior as early as 2004, but the 2017 version goes much further, identifying the very purpose of the charter as the achievement of sustainability. In addition, the new preamble places leadership responsibility squarely on the private sector, declaring, “The role of a corporation is to take the lead in the realization of a sustainable society by creating added value that will benefit society and generating employment, through autonomous and responsible behavior, on the basis of fair and free competition.”

By calling on businesses to become active agents of social transformation, instead of settling for the passive goal of maintaining good relations with stakeholders, the new subtitle heralds an important shift in the relationship between business and society. This new view is predicated on the idea of industry as driving the kind of systemic transformation envisioned by the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. From its subtitle to its core principles and implementation guidelines, the 2017 charter adopts a more proactive, forward-looking tone reflecting society’s rising expectations of private industry.

One of the driving factors behind these rising expectations is the Paris Agreement. This groundbreaking international accord calls not merely for a reduction in carbon emissions but for net zero emissions by the second half of this century with the aim of holding the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

Unfortunately, the agreement does not guarantee a bright future for our planet. Even if all the signatories achieved their current targets for reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, it would not be nearly enough to keep global warming within the 2°C threshold. Getting countries to revise those targets upward is a major issue that remains to be addressed. But the difficulty of the challenge is the very reason advocates for the global environment are looking to the combined strength of the governmental and nongovernmental sectors—and especially to the power of private industry.

To harness this power, the 2017 Charter of Corporate Behavior calls on businesses to participate actively in the creation of Society 5.0—a sustainable economy that makes optimum use of advanced digital technology, including robotics and artificial intelligence, to deliver on the SDGs without sacrificing growth and quality of life. The term “Society 5.0” originally appeared in the Japanese government’s 2016 Science and Technology Basic Plan as the core concept of a new growth model. It refers to a sustainable and inclusive people-centered society that makes optimum use of cutting-edge technology to find solutions to social and environmental challenges while meeting the diverse needs of its individual members. The concept places considerable emphasis on the contribution of private industry, with its unique potential for transformative innovation.

No One Left Behind—Toward Inclusive Growth

Inclusiveness is a key principle of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, summed up in the admonition to “leave no one behind.” On the international level, this principle has received particular attention in the context of “inclusive growth,” a term that has come up repeatedly in G7 and G20 statements in recent years.

Behind the emphasis on inclusivity lies the awareness that economic growth in this century has disproportionately benefited the wealthy. According to a January 2017 report by Oxfam, eight men now own the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of the world. Moreover, the gap between rich and poor is growing all the time.

Environmental degradation is not the only threat to sustainability. The definition of sustainable development (as set forth by the Brundtland Commission, which coined the term) is “the kind of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” To be sustainable, economic development must simultaneously address these two most basic global problems, environmental degradation and poverty. The SDGs frame this imperative in the form of 17 goals, including concrete indicators and targets to measure humanity’s progress.

Of course, eradicating poverty while combatting climate change is not a short-term undertaking. And to accomplish it over the long term will require a change extending from our social systems to our basic values. Such a transformation cannot be carried out without a strong commitment and collective action from all stakeholders. This, indeed, is the basic message of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Economic growth is vital if we are to solve the poverty problem. But that growth must be inclusive. As private industry leverages digital technology to catalyze a systemic transformation, it must not neglect this aspect of sustainability. How can business contribute to economic equality and the development of a truly inclusive society that guarantees equal rights and equal opportunity for all?

Human-Rights Due Diligence

Another important facet of social responsibility today is a company’s obligation to safeguard human rights at every stage of the value chain. The key concept here is “due diligence.” As set forth in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, due diligence is an ongoing management process for preventing and mitigating adverse human-rights impacts. It entails the adoption of a human-rights policy and the creation and implementation of an effective human-rights management system, including mechanisms for identifying problems and addressing them promptly, as well as processes for reporting corporate policies, initiatives, and outcomes to the public.

Keidanren’s implementation guidelines for principle 4 (respect for human rights) of the 2017 Charter of Corporate Behavior provide concrete guidance on human rights, anchored in the concept of due diligence and organized under the following headings:

4-1. Understand and respect human rights as an internationally recognized norm.

4-2. Clarify policies for respecting human rights and integrating them throughout business operations. (This section includes an explanation of human rights due diligence.)

4-3. Contribute to the creation of an inclusive society by supporting the independence of socially vulnerable people who are at greater risk of human rights violations, through collaboration with a diverse range of stakeholders.

Keidanren’s efforts to promote social responsibility via the charter and other initiatives did not end with the 2017 revision of the Charter of Corporate Behavior. Since June 2018, the organization has redoubled its consciousness-raising efforts under the leadership of the SDGs Promotion Bureau (formerly the Education & CSR Bureau).

The Role of Top Management

As we have seen, companies today are being called on to take a longer view than ever before to build sustainability into their business strategies with the aim of propelling social transformation. The purpose of CSR has changed, from just a means of securing public trust to something that can drive the transformation to a sustainable society. This change coincides with the dawn of an era in which corporate value is tied to sustainability, for better or for worse.

The Charter of Corporate Behavior has long stressed the leadership role of top management in initiating corporate commitment and creating a culture of social responsibility. Under the newest version of the charter, with its emphasis on industry as the driver of transformative change, the top executive plays a more critical role than ever. After all, no one but the chief executive officer can chart a course for sustainable management and set the company’s priorities accordingly. The newest implementation guidance document urges chief executives to exercise strong leadership in the pursuit of the SDGs and states our expectation that top management will “work actively to understand and display its commitment to business activity oriented to ‘the achievement of a sustainable society,’ which is the driving spirit of the Charter of Corporate Behavior and the principle of the SDGs.”

The CEO Guide to the SDGs, published by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, goes a step further, suggesting that a new brand of business leadership is needed to pave the way for substantive progress toward the SDGs. It calls on CEOs not merely to provide strong leadership within their own companies but also to take the initiative at the industry and policy-making levels.

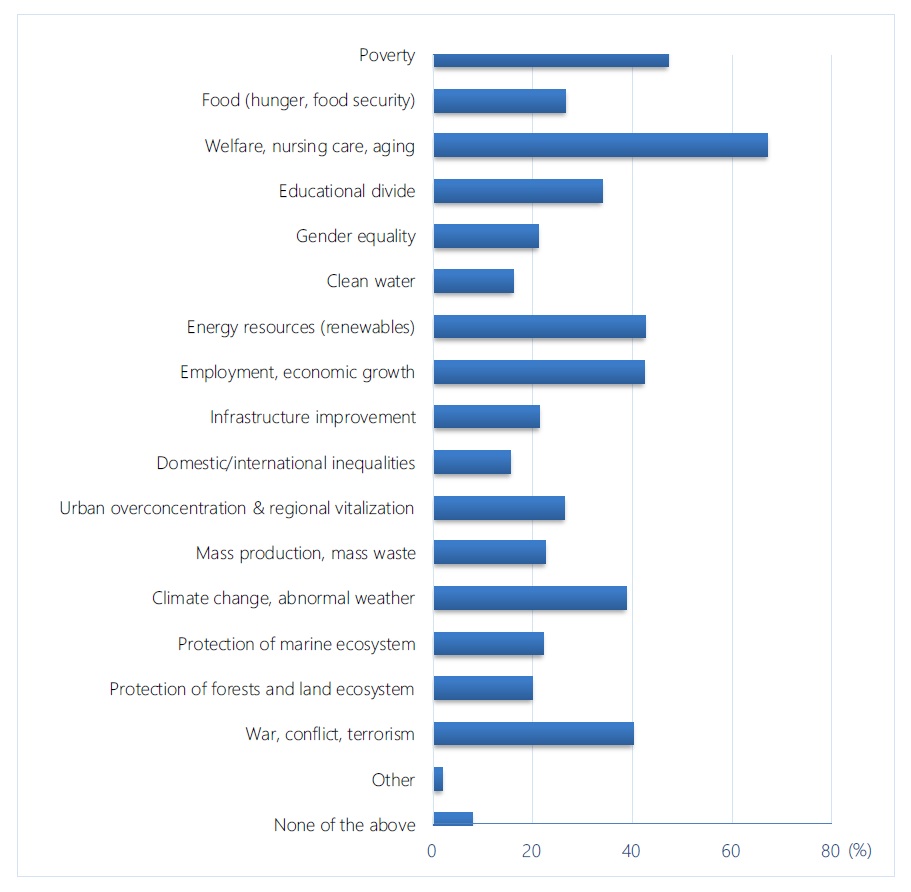

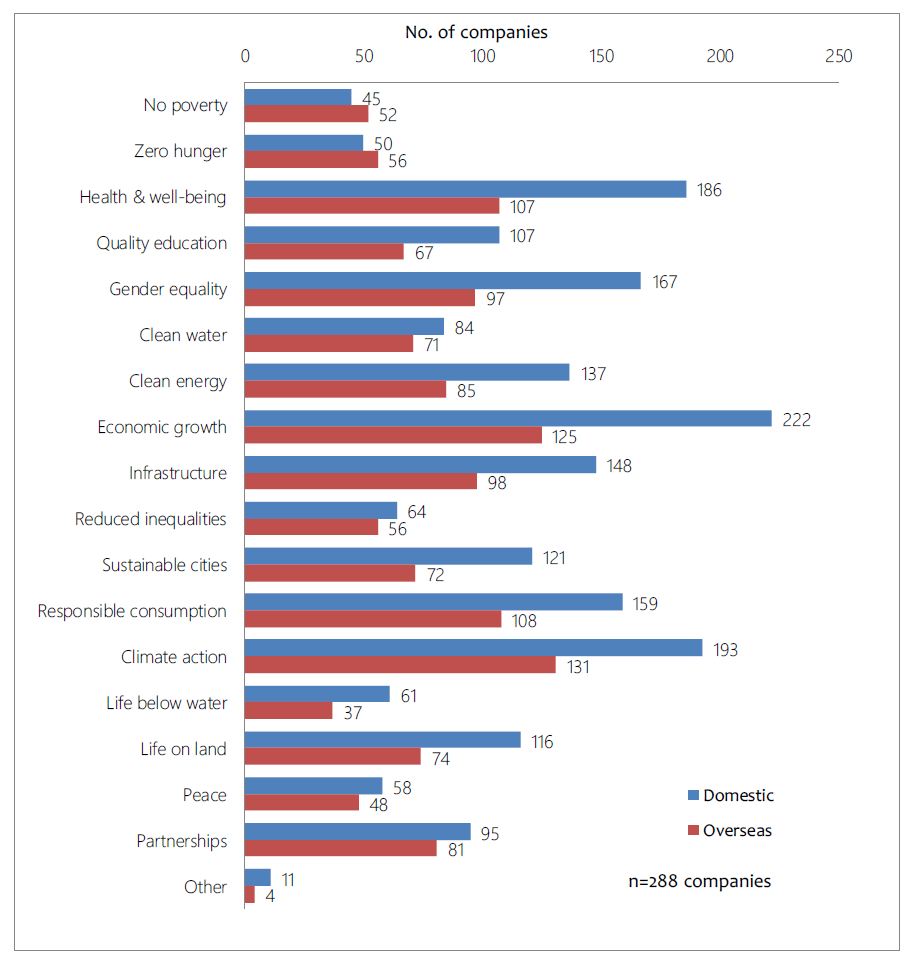

Closing the Priority Gap

The results of recent surveys reveal a “priority gap” between the business community and the general public with respect to the issues targeted by the SDGs (Figures 2 and 3). In Japan, a large proportion of the citizens surveyed identified aging, poverty, and peace issues as matters of public concern, while businesses tended to focus on economic and environmental issues, along with health and welfare. Of course, the two surveys pose different questions, making a direct comparison difficult. One can also argue that businesses and individuals are bound to have somewhat different concerns and priorities. Nonetheless, the magnitude of the discrepancy may be a sign that businesses need to be more responsive to stakeholders’ changing expectations. This is all the more important if we agree that the role of business today is to work toward the long-term resolution of humanity’s problems.

One of the key challenges facing Japanese corporations is to become better at responding to public expectations and incorporating the voice of external stakeholders so as to close the priority gap. To this end, management needs to redouble and expand its efforts to engage stakeholders in productive dialogue, focusing particularly on civil society organizations, which are quick to pick up on society’s changing needs.

We should also make note of the yawning perception gap between Japanese businesses and international stakeholders when it comes to human-rights issues. Only a paltry number of Japanese companies today exercise due diligence in accordance with international guidelines. Moreover, businesses need to go beyond due diligence. They need to show respect for human rights not merely by avoiding infractions, as an aspect of risk management, but also by offering solutions oriented to society’s vulnerable members in order to build an inclusive society (a point highlighted in the 2017 implementation guidelines). The world’s leading socially responsible companies are already finding ways to leverage their unique strengths for this purpose.

In recent years Japanese businesses have begun to take heed of one particular group of external stakeholders, namely, institutional investors. In 2015, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund became a signatory to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment and began using environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria in its investment decisions. Since then, interest in ESG investing has skyrocketed among Japanese investors and businesses, however belatedly.

Japan’s Stewardship Code and Corporate Governance Code call for active dialogue between businesses and investors on issues impacting corporate value over the medium term. But such interaction is still in its infancy. It will take time for both sides to learn the art of genuinely productive dialogue.

Figure 2. Areas of Concern for the General Public in Japan

Source: Sompo Japan Nipponkoa Insurance, “Questionnaire Survey on Social Issues and the SDGs,” March 2018.

Figure 3. Priorities for the Business Sector

Source: Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research, CSR White Paper 2018.

The Enduring Meaning of Social Responsibility

What are society’s expectations of business in the age of the SDGs?

The first and most important way to grasp one’s responsibility is to fully understand the SDGs themselves. It is not enough to stare at the colorful array of headings until one has all 17 goals memorized. One must read the entire text ("Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development") to gain a coherent and substantive understanding of the document’s background, principles, goals, targets, and action agenda.

One thing that becomes clear when one reads the 2030 Agenda carefully is the importance of human rights as the common theme uniting all the SDGs. The overriding goal of securing a healthy, fulfilling, dignified life for all human beings comes up again and again, not just in relation to poverty and economic inequality but also in connection with the environment, aging, and other challenges. One realizes that the SDGs are not just a shopping list of unrelated goals. The principle of human rights ties them together and reveals their interdependence. Running through all the SDGs is the vision of a people-centered society. And that vision is also at the heart of the Japanese concept of Society 5.0.

The Charter of Corporate Behavior is a code of conduct agreed on by Keidanren’s member corporations, and each member must accede to all 10 principles. In this, the charter resembles ISO 26000. Companies must apply itself to all seven “core subjects” of the ISO guidelines for social responsibility, including the environment, human rights, labor practices, and fair operating processes; cherry picking is not permitted. The same can be said for the 10 principles of the Keidanren Charter of Corporate Behavior. Having embraced the 10 principles, each business exercises its own judgment and creativity (with help from the implementation guidelines) to develop policies and programs consistent with them.

Today, we are witnessing a surge of interest in the SDGs as a business opportunity, and companies are being encouraged to focus on goals and targets where they can expect to have a substantive impact. In this way, the thrust of CSR is shifting toward positive impacts and the strategic merits of creating social value. But amid the enthusiasm for the SDGs, we must not forget the broader concept of CSR, including responsibility for negative impacts.

To approach the SDGs strictly as a business opportunity, divorced from the broader concept of corporate social responsibility, would be very dangerous indeed. Companies that try to cash in on the SDGs without understanding and embracing the principles of social responsibility that underlie them will ultimately be unmasked as hypocrites. The SDGs should be viewed as an invitation to enter a new phase in the evolution of CSR—an evolution clearly mirrored in the history of the Keidanren Charter of Corporate Behavior.