- Policy Proposal

- Tax & Social Security Reform

Tax and Social Security Policies for Work-Style Reform

October 15, 2019

Introduction

Among the major economic policy goals set forth by the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is “work-style reform,” a campaign to bring Japan’s employment systems and practices into step with our rapidly changing society and economy. This reflects a recognition that we must do more to accommodate the diverse needs of today’s workers—including the need to balance work with childcare and care of the elderly—in order to restore Japan’s economic vitality amid an aging and shrinking population.

The government’s Council for the Realization of Work-Style Reform, chaired by the prime minister himself, released its reform plan in March 2018. The Action Plan for the Realization of Work-Style Reform explains the government’s basic stance as follows:

The greatest challenge we face in revitalizing Japan’s economy is work-style reform. . . . Work-style reform is our best hope for raising labor productivity. By distributing the benefits of increased labor productivity to the workers, we can establish a “virtuous cycle of growth and distribution,” in which rising wages fuel expanding demand and spur economic growth. . . . With the employment environment looking up, now is the time for government, labor, and management . . . to tackle this challenge together.”

With work-style reform, the report asserts, “people will lead richer lives. The middle class will grow, consumption will rise, and more people will be able to enjoy a full and satisfying home life.”

The plan proceeds to outline nine policy goals, such as improved conditions for “nonregular” employees (including equal pay for equal work), higher wages and productivity, curtailment of excessively long working hours, and creation of an environment conducive to flexible work styles. Conspicuously absent from the plan, however, are concrete proposals for adjusting the nation’s tax code, social safety net, and labor laws to ensure fair treatment of those engaged in flexible and nontraditional modes of work.

Under the heading of “flexible work styles,” the plan advocates telework as “an effective means of balancing childcare and nursing care with work and enabling various people to show their abilities” and argues that “side jobs and multiple jobs” (held concurrently) can facilitate the development of new technologies, open innovation, entrepreneurship, and preparation for a second career after retirement. However, as the authors themselves point out, the term “telework” encompasses disparate work styles. The report identifies two basic types: “employment-type telework,” a flexible workplace arrangement offered to payroll employees, and “non-employment-type telework,” referring to services provided by freelancers and independent contractors working from home.

In this context, it notes the rise of Internet crowdsourcing services (platforms) that match freelance crowdworkers (also known as “gig workers”) to temporary jobs. It also acknowledges that such workers are vulnerable to labor abuses, including excessive workloads, low compensation, and late payment. But it makes no real commitment to protect non-employment-type teleworkers from such abuses, merely pledging to set up an expert panel to “study the need for legal protection as a medium-to-long-term issue.”

The plan is also silent on the need to bring the tax and social security systems into step with the new economy. This is not for lack of awareness of the issues. For example, the minutes of the March 14, 2017, meeting of the Industrial Structure Council’s New Industrial Structure Committee (under the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry) point to concerns over the fact that freelance workers and independent contractors, whose numbers are on the rise, must pay social insurance premiums at a substantially higher rate than regular employees (whose employers share the burden), while receiving less generous benefits. They also mention the difficulty of ensuring accurate reporting of income, and thus appropriate calculation of pension benefits, when people are working multiple jobs. Yet nowhere does the action plan discuss ways to guarantee appropriate taxation and strengthen the safety net for “non-employment-type” teleworkers.

If the government wants to encourage labor mobility and work-style diversity, it must provide the kind of safety net needed to support a mobile and flexible labor force. This means building new information infrastructure to facilitate accurate reporting of income and link tax and social security data. The United States and Europe have already taken steps to tailor their tax and social security systems to the needs and challenges of the gig economy, non-employment-style telework, and multijob workers. As long as the Japanese government defers this task, the work-style reform it envisions will not move forward.

With this in mind, the project on Integrated Reform of Tax and Social Security Systems, an undertaking of the Foundation’s Tax and Social Security Reform Unit, devoted the past year to the topic of tax and social security policies for work-style reform. After identifying seven key areas of inquiry, the project team drew up a set of policy proposals backed up by simulations and other quantitative research. We are hopeful that the results will help deepen the conversation and advance the development of policies to bring labor, taxes, and social security into step with our changing economy and society. The following is a summary of our research and recommendations in each area.

Shigeki Morinobu

Research Director, Tax & Social Security Reform Unit

Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research

Summary

Chapter 1 The Pension System and Employment of the Elderly

Takashi Oshio

Professor, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University

How should policymakers pursue the goal of boosting employment among seniors? The government’s Outline of Policies for an Aging Society (Korei shakai taisaku taiko), adopted by the cabinet in February 2018, calls for raising the maximum age at which one can begin drawing pension benefits (currently 70) and relaxing the rules governing benefits for those who work. Promoting employment of the elderly, particularly those in the 65–69 age group, is an important policy goal from the standpoint of boosting the supply capacity of the economy as a whole, funding social security, and mitigating the growing problem of poverty among the elderly.

Using data from such sources as the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, we estimated the untapped work capacity of Japan’s senior citizens, factoring in health issues. Then, with the help of data from MHLW’s Longitudinal Survey of Middle-aged and Elderly Persons, we verified the negative effect of the current public pension system on employment among the elderly and estimated the positive effect of specific changes to the system, as by relaxing the rules on working while receiving benefits and those governing delayed retirement benefits.

Proposals:

- Raise the age at which people can begin receiving public pension benefits.

- Revise the rules governing pension benefits for those who continue working.

Chapter 2 Quick Fixes for the Employees’ Pension Insurance System

Kazuhiko Nishizawa

Chief Senior Economist, Japan Research Institute, Ltd.

Japan’s current social insurance system is ill-equipped to deal with diverse work styles. It pigeonholes people into one of two categories for purposes of health insurance and retirement pensions: either regular (permanent) employees of private corporations or self-employed persons. The latter category once consisted primarily of sole proprietors of family businesses, farms, or fishing operations, but it now encompasses a growing number of freelancers and independent contractors. Regular company employees enroll in Employees’ Pension Insurance and Employees’ Health Insurance, while the self-employed are covered by the National Pension and National Health Insurance schemes. Employers are responsible for half of the premiums for those covered by Employees’ Pension Insurance and Employees’ Health Insurance, but employees whose hours total less than 75% of the standard work week for regular employees are not eligible for coverage. In many cases, the decision is effectively up to the employer, who submits the employee’s application for enrollment to the Japan Pension Service.

One result is that today, the employees of private businesses account for the largest share of those enrolled in the National Pension and National Health Insurance schemes. This and other anomalies could be remedied through procedural changes, without waiting for wholesale reform of the pension system (such as integration of the two schemes), and the benefits would be substantial.

Proposals:

- Require individual employees rather than employers to submit their applications for enrollment to the Japan Pension Service.

- Implement a withholding system for Employees’ Pension Insurance premiums.

- Require the Japan Pension Service to collate and consolidate pension records of multijob workers.

Chapter 3 Tax and Social Security Policy for the Gig Economy

Shigeki Morinobu

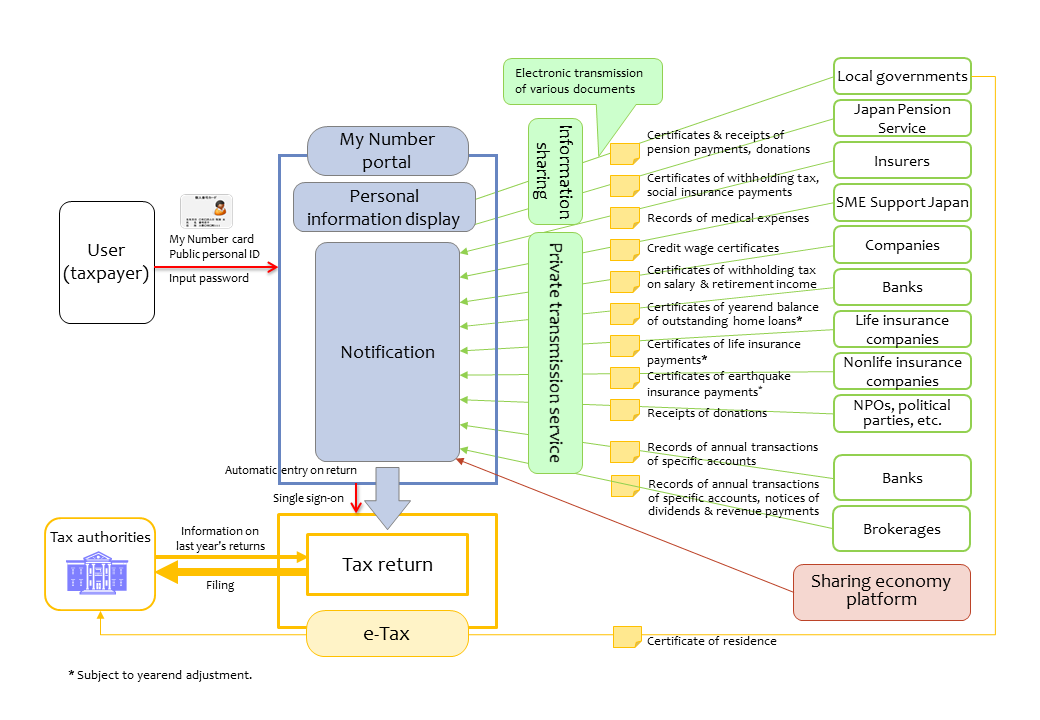

Telework tends to blur the distinction between employees and independent contractors, and since Japan’s income tax system treats employment income and business income differently, the rise of telework (as envisioned in the Work-Style Reform Action Plan) could lead to inequities in the tax burden. Scaling back the standard deduction for employees and increasing the basic exemption is one step toward enhancing fairness. But we should also consider adopting a standard deduction for business expenses to simplify income tax filing for freelance teleworkers earning under a certain amount. With the same consideration in mind, we have drawn up a concrete proposal for a system for partially prepopulated tax returns making use of advanced information technology and the individual taxpayer portals established under Japan’s new taxpayer identification (My Number) system.

Proposals:

- Establish a standard business income deduction for teleworkers earning under a specified amount.

- Develop a Japanese version of the European system of prepopulated tax returns.

Chapter 4 Income Tax Reform for Work-Style Diversity

Motohiro Sato

Professor, School of International and Public Policy, Hitotsubashi University

The Japanese income tax system draws a clear distinction between “employment income” and “business income.” Those classified as employees have their taxes withheld and receive a generous automatic standard deduction, while sole proprietors report their own business income and expenses. It is estimated that about one-fourth of the income earned by traditional sole proprietors escapes taxation owing to underreporting and the padding of business expenses (with items like rent and electricity) to maximize deductions.

Meanwhile, nontraditional sole proprietors, such as freelancers and other contract employees, complain that they are taxed more heavily than those classified as employees. Such disparities in the tax burden have the potential to distort economic activity by influencing career selection. Indeed, research conducted in other countries has demonstrated that such features of the income tax can function as a disincentive to entrepreneurship. We attempted to calculate the difference in effective tax rates paid by employees and sole proprietors, taking into account social insurance premiums and local (resident) taxes, together with the impact of various tax deductions and exemptions. We then developed a proposal for tax reform aimed at eliminating this disparity.

Proposals:

- Tax all income earned by individuals in the same manner, eliminating the distinction between “employment” and “business” income.

- Incorporate social insurance premiums into taxes and unify the definition of income under the social security, income tax, and resident tax systems.

Chapter 5 Weighing a Universal Basic Income

Eiji Tajika

Contract Professor, Faculty of Economics, Seijo University

In Japan, employers have traditionally borne a large portion of the social security burden. But the kind of permanent jobs that offer access to such benefits are dwindling, as companies boost their reliance on part-time and contract labor, along with advanced information technology. Accordingly, the idea of a taxpayer-subsidized universal basic income has gained traction as an alternative to employment-based social security. Advocates of a universal basic income call for a flat tax rate with as few deductions as possible and a guaranteed basic income through either a refundable tax credit or an across-the-board subsidy. A related idea is the negative income tax proposed by American economist Milton Friedman. This basic concept has already been put into practice in many countries in the form of an earned income tax credit and credits for childcare expenses.

This chapter explains the concept of a universal basic income and consider the design of a tax and social security system to replace the current employer-based system and respond to the needs of a changing society. An attempt is made to clarify the pluses and minuses of a basic income, taking into account the results of Finland’s experiment.

Proposals:

- A universal basic income should not be viewed as a silver bullet.

- Advocates need to address problem areas and propose realistic funding solutions.

Chapter 6 Calculating the Impact of Income Tax Reforms on Economic Inequality

Takero Doi

Senior Fellow, Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research

Professor, Faculty of Economics, Keio University

Since 2013, the Japanese government has adopted a series of income tax reforms (including some that have yet to come into effect) aimed at reducing economic disincentives to work-style and workforce diversity. Prominent among these reforms are changes to the deduction for dependent spouses, which has had the effect of limiting women’s participation in the labor force.

Changes in the basic exemption, the earned-income deduction for employees, and pension-income deductions—all set to come into effect in fiscal year 2020—are also aimed at fostering greater work-style diversity. Using data from the Japan Household Panel Survey, microsimulation analyses were conducted to determine the impact of these reforms on household disposable income and, by extension, on economic inequality.

Proposals:

- Replace income tax deductions with tax credits.

- Further reduce income tax deductions (including the pension-income deduction) for high-income taxpayers.

Chapter 7 Impact of Income Redistribution, the Child Allowance, and Student Aid on Economic Equality and Growth

Kazumasa Oguro

Professor, Faculty of Economics, Hosei University

Japan is facing three major economic challenges as it copes with the impact of demographic aging and economic globalization: placing government finances on a sustainable footing, boosting economic growth, and reducing economic inequality. Economists agree on the need to raise labor productivity in order to achieve a higher level of growth, but there is also a clear need for family-friendly policies to boost the birthrate. Among the policies under review are expansion of educational aid, increases in the child allowance, and stepped-up income redistribution via reform of the tax and social security systems. How should the government prioritize its policies amid these competing demands?

As one of the foundations of human-capital accumulation, access to education supports economic growth while also promoting income equality. But today, with economic disparities growing, children in lower-income households are increasingly denied opportunities for higher education. Some critics have warned of a vicious circle that could become a drag on economic growth. In this context, there is growing support for increased student aid as a means of addressing economic inequality while promoting economic growth. Nonetheless, there is disagreement over the relative importance of such policies as opposed to the child allowance or income redistribution via the tax and social security systems. In an effort to aid policy prioritization, we conducted simulations to gauge the relative effect of four policy scenarios: the status quo, enhanced income redistribution, expansion of the child allowance, and increase in educational assistance, including government loans for higher education.

Proposals:

- Rethink policy priorities (with emphasis on educational assistance).

- Expand the Income Contingent Loan scholarship program.