- Article

- Industry, Business, Technology

The SDGs and ESG Investing: Toward a New Era of Responsible Capitalism

March 11, 2020

In Japan, the rise of ESG investing has been closely linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which have taken hold faster than anyone anticipated. Awareness of ESG investing in this country began to surge in late 2015, after the Government Pension Investment Fund—the world’s largest public pension fund—became a signatory to the Principles for Responsible Investment. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced that decision in his address to the UN General Assembly on September 27, 2015, after the member nations unanimously approved the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with its SDGs.

Under the circumstances, the confusion between ESG and the SDGs among Japanese business managers, goverment officials, civil society workers, and educators is understandable. In reality, however, the origins of ESG investing predate the SDGs by almost a century. In the following, I offer a brief overview of the concept and its development, its more recent linkage with the SDGs, and its impact on corporate finance in Japan.

A Brief History of Sustainable Investing

ESG investing is an approach to investment decisions that takes into account environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) criteria, in addition to financial data. In its attention to nonfinancial criteria, it is closely related to socially responsible investing. SRI is generally traced to a trend that emerged in the 1920s, as American churches with assets to invest made the decision to exclude certain businesses, such as the alcohol industry, from their portfolios on moral grounds.

Responsible investing reemerged in the 1960s and 1970s, albeit in different form, when the civil rights and antiwar movements were at their height. Shareholder activism surged to the fore around this time, as investors used annual shareholder meetings as a forum to pressure companies to change, calling, for example, for Dow Chemical to stop producing Agent Orange and for General Motors to name a person of color to its board of directors. Throughout this period, however, SRI remained a distinctly nonmainstream approach to investment embraced by adherents to a particular religion or social movement.

The dynamic began to change again in the late 1990s and early 2000s, as the concept of corporate social responsibility began to take hold. Amid a growing awareness of the environmental impact of big business, the International Organization for Standardization published the ISO 14000 series of standards for environmental management in 1996, spurring major reforms among Japanese manufacturers. In Europe, where social inclusion had emerged as an issue on the eve of unification, businesses were called on to meet their social responsibility by providing decent jobs and career opportunities for immigrants and people living in poverty. The US apparel industry, notably Nike, came under scrutiny for relying on an international supply chain that included companies using child labor, leading to large-scale student boycotts. In the early years of the twenty-first century, the Enron scandal broke, revealing massive failures in governance and resulting in the firm’s collapse, and a food-poisoning scandal dealt a serious blow to Japan’s leading dairy producer. At the same time, Toyota Motor helped revolutionize the auto industry with its hybrid Prius, launched the year when the Kyoto Protocol was adopted, winning kudos as an exemplar of environmental management.

These developments in the 1990s and early 2000s demonstrated the need for businesses to confront the risks and opportunities associated with such nonfinancial issues as regulatory compliance, environmental stewardship, business ethics, fair labor practices, workforce diversity, and human rights in the supply chain. This led a growing number of investors to conclude that assessment of companies’ management and performance in such areas was critical to ensure sound long-term investment decisions. Coinciding with this global trend was the 1999 launch of Japan’s first Ecofund—an investment trust that included environmental management among its investment criteria. For a time, such funds were quite popular among individual investors.

As time went on, more and more investors began incorporating nonfinancial information in their own investment activities. These movements went by such names as green or sustainable investment, ethical investment, and socially responsible investment, depending on their religious, moral, or performance focus. Together, they began to gather significant momentum among Western institutional investors.

These diverse currents merged in 2006 in the form of the Principles for Responsible Investment, drafted and adopted by representatives of some of the world’s largest institutional investors under the leadership of the UN Environmental Programme Financial Initiative and the UN Global Compact. Institutional investors signing onto the PRI embrace the six principles in Figure 1. In 2006, at the time the PRI went public, there were 68 signatories, including financial behemoths like the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, Britain’s Hermes Investment Management, and the Government Pension Fund of Norway. By April 2019, the number had risen to 2,372 institutions spanning the globe, turning PRI into a nexus for ESG investing.

Figure 1. The Six Principles for Responsible Investment

|

1. We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes. |

|

2. We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices. |

|

3. We will seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entities in which we invest. |

|

4. We will promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry. |

|

5. We will work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the Principles. |

|

6. We will each report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles. |

Source: UN Principles for Responsible Investment, https://www.unpri.org/pri/an-introduction-to-responsible-investment/what-are-the-principles-for-responsible-investment.

The term ESG has its origin in the text of the Principles for Responsible Investment, beginning with the preamble, which states:

As institutional investors, we have a duty to act in the best long-term interests of our beneficiaries. In this fiduciary role, we believe that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues can affect the performance of investment portfolios (to varying degrees across companies, sectors, regions, asset classes and through time). We also recognise that applying these Principles may better align investors with broader objectives of society.[1]

The PRI defines responsible investment as “a strategy and practice to incorporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions,”[2] and it holds that the application of ESG criteria can enhance investors’ portfolio performance while at the same time advancing broader social goals—a “win-win” for investors and society. With the publication of the Principles, use of the term ESG gradually spread, along with the Principles themselves. The GPIF, in announcing its decision to become a signatory to the PRI, stated, “It is our belief that considering Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) issues properly will lead to increase in corporate value, foster sustainable growth of the investee companies, and enhance the medium- to long-term investment return for the pension recipients.”[3]

Branding can have a big impact on how quickly and widely trends and concepts spread. I believe that adoption of the term “ESG investing” is one factor contributing to the spread of responsible investment, at least in Japan. Partly owing to the connotations of the term shakaiteki sekinin (social responsibility), Japanese institutional investors were wary of “socially responsible investing,” feeling that it prioritized religious values or social ideology over the fiduciary responsibility to maximize returns. ESG has a more neutral nuance, and the PRI makes it clear that ESG criteria can add an important dimension to investee assessment, thereby contributing to better portfolio performance.

“Sustainable investing,” which has a similar nuance and can be applied to asset classes besides shares (bonds and real estate, for example) is also used by some Japanese organizations, including the Japan Sustainable Investment Forum, of which I am a chief executive, but it is losing ground to “ESG,” which is easier to write and pronounce.

Assessment, Engagement, and the SDGs

As the foregoing demonstrates, ESG investing has expanded independently of the SDGs, and its spread signifies a growing understanding that the inclusion of environmental, social, and governance factors in investee assessments is likely to translate into higher performance over the long run. According to a report by the PRI, out of more than 2,000 studies on ESG and performance published since 1970, only 10% found a negative link, while 63% found a positive link.[4]

Accurate ESG analyses rely on a wide range of information, from regularly updated quantitative data (such as carbon dioxide emissions and the number of women on the board of directors) to qualitative factors that cannot be expressed numerically (policies to protect the environment, support diversity in the workforce, protect human rights in the global supply chain, and so forth). The rise of ESG investing has thus been accompanied by the development of various tools to collect and assess such information.

One notable example is the climate change questionnaire that the international nonprofit CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) began sending in 2002 to top global firms in response to investor inquiries. The CDP releases the results publicly, along with assessments and rankings of individual companies. The service has since branched out from climate change to other topics in ESG management, soliciting disclosure on forest commodities, water security, and supply chain management. The CDP has become widely known in the CSR and investment communities today, but when it was starting out, it made great efforts to explain why investors cared about climate change issues, and it worked long and hard to enlist companies’ cooperation.

The PRI, meanwhile, actively promotes dialogue between investors and individual investee companies on ESG issues of material significance to those businesses. For example, Climate Action 100+ is “an investor initiative to ensure the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take necessary action on climate change.” Launched in 2017, the initiative has enlisted more than 300 PRI signatories and other investors in a campaign to accelerate the transition to clean energy by engaging with the 100 “systemically important global emitters” and 61 other trendsetting companies.[5]

In this context, the SDGs have emerged as a valuable tool for investors and others eager to identify material ESG issues, gather the relevant data, and encourage companies to change the way they do business. In essence, they offer a complete menu of ESG topics and subtopics along with a framework for assessing companies’ performance in each area. They also provide a common language by which governments, companies, and nonprofits, as well as investors, can communicate and collaborate on issues of common concern.

The Dawn of SDG Investing

For these reasons, more and more ESG investors and ratings services are adopting the SDGs as a framework for assessment. In September 2016, a group of Dutch asset managers (PGGM, APG, etc.), together with Sweden’s AP buffer funds, signed a statement of their intent to use the SDGs as a common framework for investment decisions. The following December, 18 Dutch institutional investors formed the SDG Investing Initiative and released a proposal titled “Building Highways to SDG Investing,” outlining recommendations for more active investment in the SDGs in collaboration with the national government and the central bank.

In January 2017, the Positive Impact Working Group of UNEP FI, consisting of 19 major financial institutions worldwide, adopted the Principles for Positive Impact Finance, a “common framework to finance the Sustainable Development Goals.”[6]

A PRI report titled “The SDG Investment Case,” released in October 2017, offers five basic arguments for the relevance of the SDGs to institutional investors, as follows.[7]

|

1. The SDGs are the globally agreed sustainability framework |

|

2. Macro risks: The SDGs are an unavoidable consideration for “universal owners” |

|

Large institutional investors with highly diversified long-term portfolios need to encourage sustainable economies and markets in order to improve their own long-term financial performance, which depends on the health of the overall economy. |

|

3. Macro opportunities: The SDGs will drive global economic growth |

|

The SDGs are a formula for healthy, sustainable economic growth achieved without overburdening communities or the environment. Macroeconomic growth is the fundamental driver of growth in corporate revenues and earnings, which in turn drive returns from equities and other assets. |

|

4. Micro risks: The SDGs as a risk framework |

|

At some point in the future, companies will probably be obliged to assume a significant portion of currently external costs (such as the environmental burden of greenhouse gases). The SDGs provide a frame of reference for assessing such risk. |

|

5. Micro opportunities: The SDGs as a capital allocation guide |

|

Companies that shift toward more sustainable business practices and products with the SDGs in mind will generate new opportunities for investment. The SDGs provide a common language with which to shape and articulate such an investment strategy. |

In addition, the report explains that, for PRI signatories and others committed to responsible investment, the SDGs and their targets provide a way to measure the social impact of ESG investing and demonstrate the real-world impact of their investment approach.

Directing Capital Flows to Achieve the SDGs

The SDGs themselves are explicit about the role of investment and bank financing in sustainable development. Among the economic targets set forth under Goal 17, Partnerships for the Goals, are those to mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries (17.3), assist developing countries in attaining debt sustainability and reducing the debt risk of highly indebted poor countries (17.4), and adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least-developed countries (17.5).[8]

Financial institutions have an important role to play in promoting progress toward the SDGs by channeling funds to responsible businesses and sustainable solutions. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has estimated that an additional investment of $5 trillion–$11 trillion annually will be required to achieve the SDGs. For the developing world alone, the estimate is $3.3 trillion–$4.5 trillion for basic infrastructure, food security, climate-change mitigation and adaptation, health, and education.[9]

Buying shares in listed companies that contribute to the SDGs can help, but stock market investments alone will not be sufficient to finance the achievement of the SDGs. Funding specific initiatives and projects offers greater promise, as does purchasing green bonds and social bonds, the proceeds of which are applied exclusively to qualifying environmental or social projects. The International Capital Market Association has worked to enhance transparency in this area by publishing principles and guidelines for issuers and investors. It also publishes “Green, Social & Sustainability Bonds: A High Level Mapping to the Sustainable Development Goals,” a framework for evaluating the objectives of specific special bonds in relation to the SDGs.[10]

ESG Trends in Japan

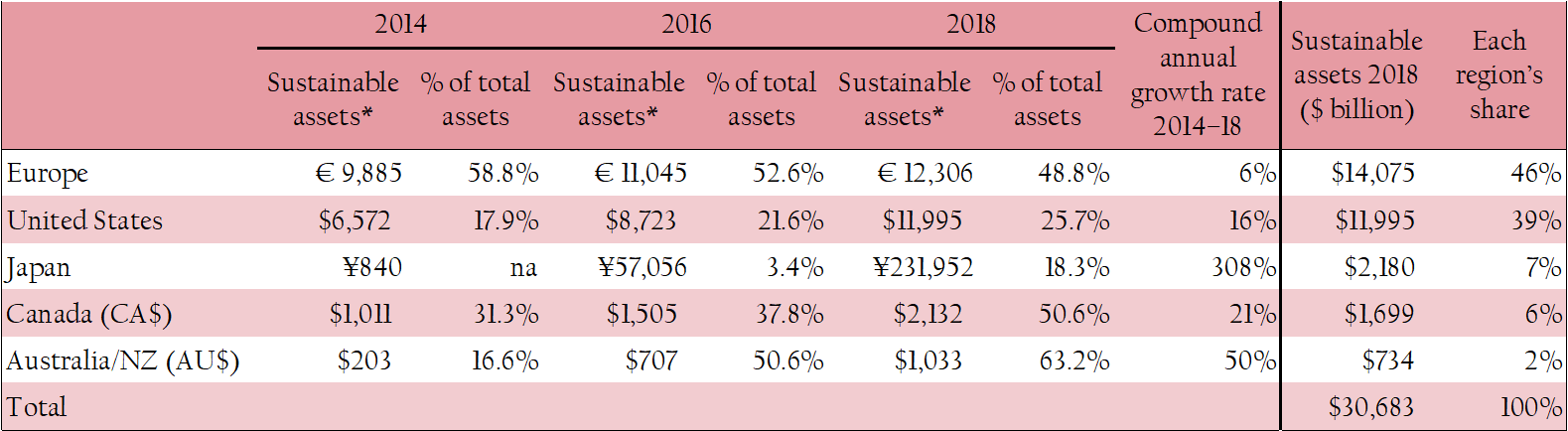

How has Japan responded to these global trends? Three major changes can be observed. The first that we have seen in recent years is the rapid growth of ESG investing since the GPIF became a signatory to the PRI. According to figures published by the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, the value of Japan’s sustainable-investment assets grew at a compound annual rate of 308% between 2014 and 2018, much higher than other markets, and its share of the global sustainable-investment market rose to 7% (Figure 2). In addition, the number of Japanese signatories to the PRI has more than doubled since August 2015 (before the GPIF signed), rising from 33 to 70, as of April 2019.[11]

Figure 2. Growth of Global Sustainable Investment Assets by Region

Source: Adapted by the Daiwa Institute of Research from Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, Global Sustainable Investment Review 2018, http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GSIR_Review2018.3.28.pdf.

* Each region’s asset values are expressed in billions of the local currency. All 2018 assets are as of December 31, 2017, except for Japan, whose assets are as of March 31, 2018.

Needless to say, this trend has been accompanied by operational changes within the financial services industry—most obviously, the assigning of ESG specialists by each asset management firm to track and analyze data pertaining to such issues as climate change, deforestation, diversity, and human rights in the supply chain. The view that information on environmental and social issues—widely viewed as peripheral at best five years ago—is integral to asset management and financing is becoming mainstream. According to the Japan Sustainable Investment Forum, which compiled the data for Japan used in Figure 2, the number of Japanese organizations responding to the forum’s Sustainable Investment Survey rose from 31 in 2016 to 42 in 2018, and among responding companies, ESG investing as a share of total investment assets under professional management jumped from 16.8% to 41.7% during the same period.[12]

Industry groups representing the Japanese financial services sector have responded as well. In September 2017, the Japan Securities Dealers Association established the Council for Promoting the SDGs in the Securities Industry. In March 2018, it issued a Declaration in Support of the SDGs, pledging to undertake initiatives to end poverty and starvation, protect the global environment, promote decent working conditions and women’s participation in society, support education for the socially vulnerable, and improve awareness and understanding of the SDGs.[13]

The Japanese Bankers Association, meanwhile, revised its Code of Conduct in March 2018 to include a provision articulating the industry’s commitment to the SDGs. The new Code of Conduct stresses the need to address such social challenges as human rights and the environment and calls on financial institutions to provide funding and other forms of support for those efforts.[14] The JBA also established an organizational framework and a set of outcomes-based initiatives for pursuing the SDGs.

The third area of progress is government policy. In June 2018, the Financial Services Agency published its strategy to “work proactively” to achieve the SDGs, which it characterizes as consistent with the government’s financial goals of “enhancing the nation’s welfare through the sustained growth of business and the economy and the steady creation of wealth.” In the document, the FSA states that the SDGs are by nature goals to be pursued voluntarily at the initiative of businesses, investors, and financial institutions. At the same time, it acknowledges the responsibility of the FSA to take action to promote balanced, sustainable economic development in the event that private-sector initiatives fall short for whatever reason.[15] In March 2019, the agency appointed a chief sustainable finance officer to promote these efforts.

In January 2018, the Ministry of the Environment created a high-level advisory panel on ESG finance consisting of top officers from the financial sector’s major industry groups. In July 2018, the panel released its recommendations under the title “Toward Becoming a Major Power in ESG Finance.” It calls for concrete action to accelerate the trend toward ESG investing and promote ESG financing in the banking industry.[16]

Each of these organizations emphasize the importance of advancing a fuller understanding of how investment and finance can contribute to the SDGs. Greater familiarity with the SDGs, in turn, can be expected to enhance financial literacy as well.

A New Era of Responsible Capitalism

As the foregoing suggests, the SDGs are pointing the way to a new era in investment and lending.

ESG investing existed before the release of the SDGs, but the SDGs have introduced new criteria for investment decisions, namely, the impact of a business or program on global progress toward sustainable development.

CEO Larry Fink of Blackrock, the world’s largest asset management firm, sums up the spirit of sustainable investment eloquently in his 2019 letter to CEOs, titled “Profit and Purpose.” “Profits and purpose are inextricably linked,” he says. “Profits are essential if a company is to effectively serve all of its stakeholders over time. . . . Similarly, when a company truly understands and expresses its purpose, it functions with the focus and strategic discipline that drive long-term profitability.”[17]

The days of twentieth-century-style market fundamentalism, when greed was good, are drawing to an end. We are entering a new era of responsible capitalism in which profits go hand in hand with social purpose. The path ahead may not always be smooth or straight, but the SDGs can help light the way forward.

[1] https://www.unpri.org/pri/an-introduction-to-responsible-investment/what-are-the-principles-for-responsible-investment. Underline added by the author for emphasis.

[2] https://www.unpri.org/pri/an-introduction-to-responsible-investment/what-is-responsible-investment.

[3] https://www.gpif.go.jp/en/investment/pdf/signatory_UN_PRI_en.pdf.

[4] PRI, A Blueprint for Responsible Investment, https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=5330, p. 17.

[6] https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/POSITIVE-IMPACT-PRINCIPLES-AW-WEB.pdfhttps://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/POSITIVE-IMPACT-PRINCIPLES-AW-WEB.pdf. The participating institutions are Australian Ethical, Banco Itaú, BNP Paribas, BMCE Bank of Africa, Caisse des Dépôts Group, Desjardins Group, First Rand, Hermes Investment Management, ING, Mirova, NedBank, Pax World, Piraeus Bank, SEB, Société Générale, Standard Bank, Triodos Bank, Westpac and YES Bank.

[7] https://www.unpri.org/sdgs/the-sdg-investment-case/303.article.

[8] https://www.globalgoals.org/17-partnerships-for-the-goals.

[9] UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2014, p. xi.

[10] https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/June-2019/Mapping-SDGs-to-Green-Social-and-Sustainability-Bonds06-2019-100619.pdf.

[11] http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GSIR_Review2018.3.28.pdf.

[12] http://japansif.com/2018survey-en.pdf.

[13] http://www.jsda.or.jp/en/activities/SDGs/files/sdgsdeclaration180322_e.pdf.

[14] https://www.zenginkyo.or.jp/en/conduct/.

[15] https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/30/20190315_CSFO.html.

[16] http://www.env.go.jp/policy/01_Recommendation%28full%29.pdf.

[17] https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter.