- Article

- Tax & Social Security Reform

Agenda for Post-Pandemic Tax Reform: Targeting Inequality, Climate Change, and Tax Avoidance

December 16, 2020

Tax expert Shigeki Morinobu outlines three critical social and economic issues facing post-pandemic Japan and the tax reforms needed to meet those challenges.

* * *

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated major social and economic adjustments, triggering changes in lifestyle, consumption patterns, and values that are likely to persist long after the epidemic has subsided. Among other things, the crisis has raised our expectations of what the government can and should do. Taken together, such changes are bound to impact the tax system, which performs the dual function of funding public services and redistributing income.

In the following, I discuss some of the tax reforms Japan should pursue in order to address the problems highlighted by the pandemic and build a more advanced, equitable, and humane society.

Problems Highlighted by the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic repercussions have drawn renewed attention to three overarching issues with major implications for tax reform.

The first is the global issue of growing economic inequality. It has been well documented that COVID-19 infection and fatality rates tend to be higher among lower income groups, and the pandemic’s rapid spread among the poor has become a serious social issue in countries around the world. Unemployment resulting from the pandemic has also had a disproportionate impact on middle- and low-income earners. In Japan, the economic and social gap between regular and nonregular employees has been a festering issue for some time now, but the coronavirus has thrown the problem into high relief.

The second issue is the environment. Climate change and environmental degradation have been cited as factors contributing to the emergence and spread of new pathogens, not to mention the rising number and intensity of extreme weather events, wildfires, and other disasters. The Japanese government must get busy formulating concrete environmental policy measures if it wishes to achieve the 2050 target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions announced by Prime Minister Yoshihisa Suga in October.

The third issue is the challenge of taxing the digital economy. The COVID-19 crisis has been a windfall for such multinational tech giants as Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon. The problem is that these big tech firms do not pay their fair share of taxes. Using algorithms and artificial intelligence, they are able to convert the user data they collect at no cost to themselves into highly profitable assets, and those intangible assets are easily transferred to low-tax or tax-free jurisdictions, escaping corporate income tax.

Under current international tax rules, Japan lacks the authority to tax the profits that Japanese consumers generate for these US-based tech giants, and the same is true for other so-called “user jurisdictions.” For some time now, negotiators from countries all over the world, including many developing nations, have been working in collaboration with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to reach a consensus on new tax rules adapted to the digital economy, but progress has been slow.

To some degree, these are all global issues requiring coordinated action. But Japan can take important steps in the right direction with some well-thought-out tax reforms for the post-pandemic era.

Promoting Economic Equality

In his 2014 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the French economist Thomas Piketty called attention to the growing problem of economic inequality worldwide and made the case for a global progressive wealth tax. Even leaving aside the political hurdles, the technical challenges to the direct taxation of wealth remain formidable. Where financial assets are concerned, the widespread adoption of the OECD’s standards for automatic exchange of financial account information has made it possible for tax authorities around the world to track capital outflows and combat tax evasion (as by the use of tax havens). But that still leaves a number of high hurdles, particularly the difficulty of valuing real assets.

A more realistic option for Japan would be to enhance the redistributive function of our income taxes, particularly as regards income from assets. One proposal under discussion targets such investment income as dividends and capital gains, which are currently taxed separately from employment income at a flat 15% rate. The simplest solution might appear to be an across-the-board increase in the tax on financial income, but that would penalize the roughly 80% of taxpayers who currently pay either 5% or 10% on their employment income.

The best answer for now is probably to exempt financial income under a certain threshold from the increase. This should not be difficult now that a My Number taxpayer identification number is required to open an investment account, allowing tax authorities to track each taxpayer’s total income from dividends and capital gains, regardless of the number of accounts he or she holds. Farther down the road, the government may want to consider taxing aggregate income, but that would require mandatory linkage of all savings accounts to taxpayer numbers.

Another item on the tax-reform agenda is addressing inequities in the tax treatment of self-employed individuals engaged in “employment type” work. The number of gig workers, crowdworkers, and freelance teleworkers has soared in Japan, as elsewhere, and the coronavirus has accelerated the shift. Although many of these nontraditional workers are de facto employees, their tax status as self-employed individuals makes them ineligible for the generous standard deduction automatically granted to payroll employees. This anomaly is producing a lopsided distribution of the tax burden. It is time to think about offering the standard deduction to all workers engaged in employment-type work and earning less than a specified amount per year.

Ensuring fair taxation and income redistribution in the age of nontraditional employment will necessitate a more advanced, up-to-date tax-administration infrastructure, including a system for digital reporting of payments associated with each taxpayer number. Multinational tech firms should not be exempt from such reporting. It is up to the government to set this process in motion as soon as possible.

Stemming Climate Change

Experts agree that the Japanese government will need to leverage carbon pricing if it hopes to meet its goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. One obvious way of putting a price on carbon emissions is to impose a carbon tax. A carbon tax makes CO2-emitting fuels more expensive, thus reducing demand. It is an effective and efficient means of mobilizing the market mechanism to fight climate change.

Japan already has a carbon tax, but pressure from industry has helped to keep it very low—one of the reasons Japan gets poor marks on environmental policy, compared with the developed countries in Europe and elsewhere. It is time we started doing our part for global sustainability (bearing in mind the UN Sustainable Development Goals) by raising our carbon pricing to a level on a par with the world’s environmentally progressive nations.

To prevent such a tax from putting Japanese industry at a competitive disadvantage, Japan should consider a “carbon border adjustment mechanism” similar to that being considered by the European Union. A CBAM seeks to eliminate the cost disadvantage that a carbon tax might impose on domestic industry by levying an offsetting tax on more carbon-intensive imports. Conversely, a carbon refund can be offered when a domestically produced item is exported.

The revenue raised by such a tax could be applied in a number of ways, including green public investment, subsidies for renewable energy, or other measures to reduce carbon emissions. Some mechanism might also be introduced for returning any surplus directly to households. Our tax and energy experts will need to put their heads together to come up with the optimal policy mix.

Taxing the Tech Giants

For several years now, the OECD has been working to broker a global agreement for updating international tax rules to facilitate fair taxation of the digital economy. Initially, there were high hopes for a plan to tax the “residual profits” (defined as anything in excess of a 10% profit margin) arising from the intangible assets of the tech giants (highly digitalized, “consumer facing” multinationals). Unfortunately, the Trump administration flatly rejected such an approach as disadvantageous to America’s tech firms, and talks were put on hold. In the coming year, we need to make up for lost time and reach an international agreement before a confusing patchwork of national taxes takes shape

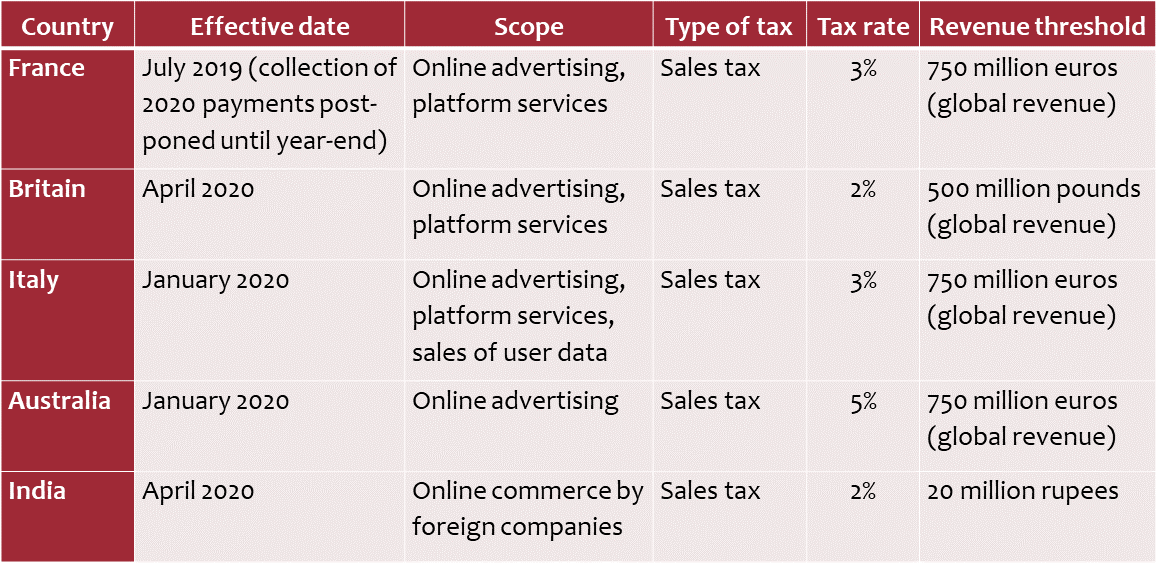

Australia, India, and several European countries are already moving to institute digital services taxes (DST), which target sales of online advertising and other digital services. Unlike corporate income taxes, which are subject to international tax treaties, these are indirect taxes and can be levied by domestic legislation alone. The Trump administration got France to postpone collection of its 2020 DST payments by initiating a Section 301 investigation and threatening high retaliatory tariffs. Nonetheless, France has announced that it intends to begin collecting the tax at the end of the year.

Major Digital Services Taxes by Country

Source: Compiled from materials published by the Japan Ministry of Finance and the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

If countries move unilaterally to tax the revenues of tech companies, the resulting chaos could hinder the sound development of digital businesses. That said, ongoing tax avoidance by multinational tech giants gives those firms an unfair cost advantage and adversely affects the ability of governments to raise much-needed tax revenue. Japan needs to begin formulating a strategy for imposing its own DST in the event that the United States continues to block an international agreement.

In addition to addressing key social and economic issues facing post-pandemic Japan, the foregoing reforms will have the effect of boosting tax revenues, thereby contributing to fiscal retrenchment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to acknowledge the need to strengthen the role of government, but that takes money. Now that the consumption tax has been raised to 10% under a comprehensive plan intended to cover the Japan’s social security needs for the foreseeable future, the nation will need to engage in a deeper conversation on the kind of safety net the government should provide and the appropriate distribution of burdens and benefits.

Translated from “Kakusa, kankyo, kyodai IT taio isoge: Korona-go no zeisei kaikaku,” Keizai Kyoshitsu, Nihon Keizai Shimbun, November 16, 2020. (Courtesy of Nikkei Inc.)