Changing Corporate Behavior to Jump-Start the New Capitalism: The North Wind Versus the Sun

March 10, 2022

R-2021-058E

There is broad agreement within Fumio Kishida’s policy team on the need for change in corporate behavior to jump-start the “virtuous cycle of growth and distribution” that is central to the prime minister’s “new capitalism” strategy. But how can such change be achieved?

* * *

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has called for a “new capitalism” in which growth yields economic resources that are distributed to fuel further growth. But what is the best way to establish and sustain this “virtuous cycle of growth and distribution”? There are a number of policy options, divided broadly between what, in Aesopian terms, might be described as the North Wind and the Sun.

Spotlight on Corporate Behavior

The November 2021 Emergency Proposal Toward the Launch of a “New Form of Capitalism,” issued by a council in the Cabinet Secretariat, summarizes the problem of stronger corporate earnings not leading to benefits for ordinary households or bullish capital spending. Citing the Japanese management philosophy of sanpo yoshi—good for the seller, good for the buyer, and good for society—the proposal stresses the need for companies “to enhance their mid- to long-term earning power by strengthening their investment in the future in areas such as human capital, and to achieve sustainable growth by circulating the profits through wage increases and other distributions as well as through further investment in the future.”

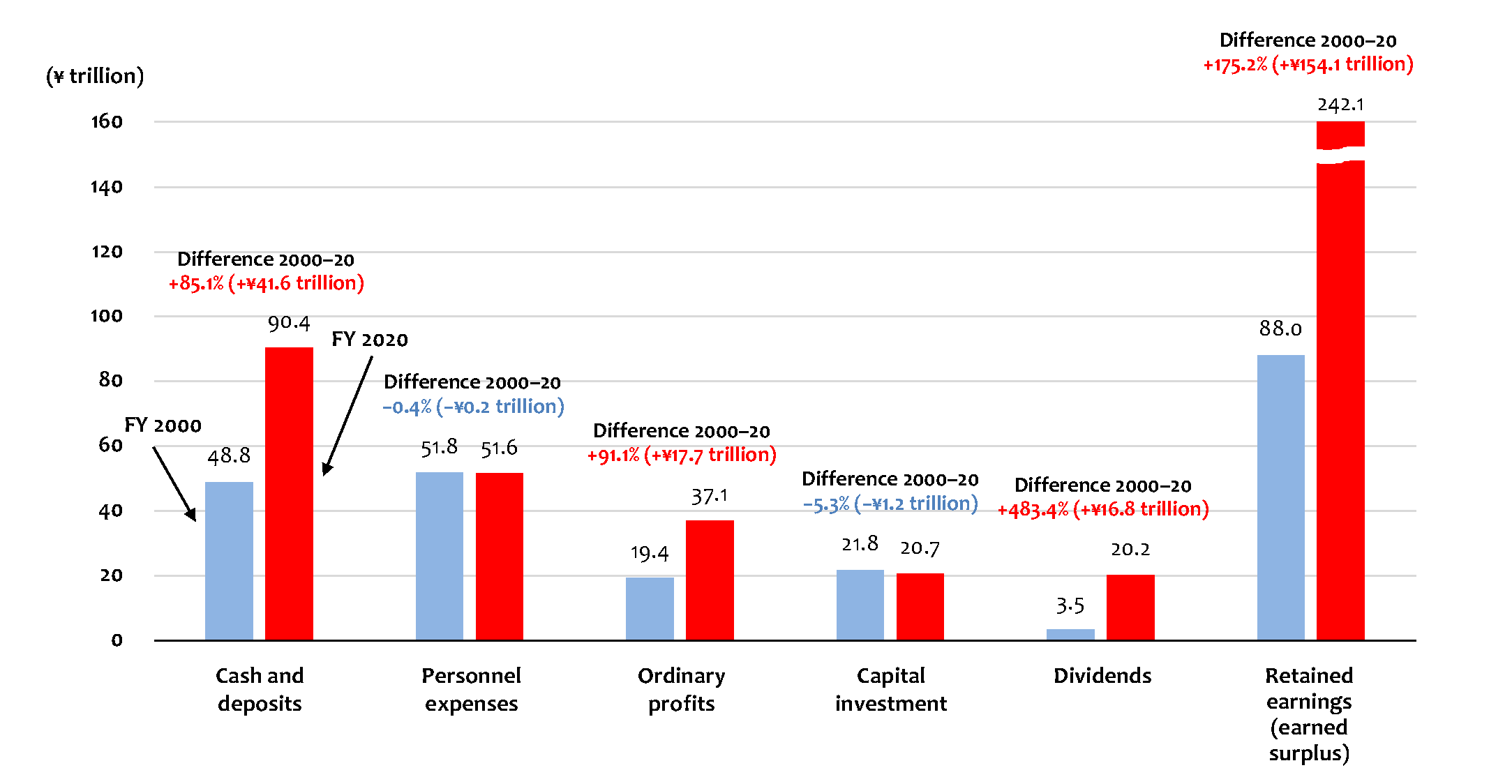

With these premises in mind, policy deliberations within the government’s Council for a New Form of Capitalism have focused on the behavior of Japanese companies, particularly as regards the distribution of profits. Analyzing corporate financial data collected over the past 20 years, the council has noted a decline in personnel expenses and investment in plant and equipment, even amid rising profits. By contrast, dividend payouts have surged, as have cash and deposits and retained earnings—the surplus profits companies have accumulated over time. The graph below, based on materials distributed at the council’s third meeting on November 26, 2021, charts these trends among Japan’s large corporations (market capitalization of ¥1 billion or more).

Financial Trends Among Japan’s Large Corporations (market cap of ¥1 billion or more)

Notes: Excludes data from financial services sector. Cash and deposits consist of cash, bank deposits, and liquid securities. Personnel expenses consist of salaries and wages, bonuses, and employee welfare expenses.

Source: Data Concerning Wages and Human Capital, distributed at the third meeting of the Council for a New Form of Capitalism, November 26, 2021. Based on Ministry of Finance survey data published as Financial Statements Statistics of Corporations by Industry.

To sum up, between 2000 and 2020, the combined ordinary profits of Japan’s large corporations rose 91.1% (up ¥17.7 trillion). During the same span, cash and deposits increased by 85.1% (up ¥41.6 trillion), and dividends rose 483.4% (up ¥16.8 trillion). Meanwhile, personnel expenses decreased by 0.4% (down ¥200 billion), and capital investment fell 5.3% (down ¥1.2 trillion). Accumulated retained earnings at large Japanese corporations rose by a full 175.2% for an increase of ¥154.1 trillion.

The council found a similar pattern among small and medium-sized enterprises (market cap between ¥10 million and ¥100 million). Between 2000 and 2020, ordinary income rose 14.9% (up ¥1.6 trillion). Meanwhile, capital investment increased by just 8.3% (up ¥800 million), and personnel expenses fell by 15.9% (down ¥12.5 trillion), while dividends soared 216.6% (up ¥1.6 trillion), cash and deposits rose 49.6% (up ¥40.1 trillion). Retained earnings jumped 92%, an increase of ¥73.4 trillion.

Based on these numbers, the council has noted that Japanese businesses have been far more intent on rewarding their shareholders than on giving back to their employees. The growing consensus is that companies need to start boosting wages in order to kickstart the virtuous cycle of growth and distribution, instead of using the bulk of their rising profits to enrich shareholders or build up their ever-growing cash reserves. Essentially, the call for a new capitalism is a push for a change in corporate behavior.

But what is the best way to bring about the desired change? Some politicians are advocating new taxes on retained earnings or on cash and deposits. These calls doubtless reflect a growing frustration with Japanese industry, which has benefited from substantial cuts in corporate tax rates in recent years without passing those benefits on to society in the form of higher wages or capital investment. But is the North Wind of taxation the best way to make the new capitalism a reality? To answer that question, let us consider some of the options available.

Drawbacks of a Retained-Earnings Tax

Retained earnings, also known as earned surplus, are a company’s accumulated surplus profits—what shows up on the balance sheet after all expenses, taxes, and dividends have been paid. It is a cumulative figure that increases with each accounting period as long as net income is in the black.

Retained earnings are not just leftover funds. This figure represents that portion of the business’s own earnings that are available (along with funds from bank loans and corporate bonds) for further business investment (including capital investment and mergers and acquisitions). On the corporate balance sheet, the results of such investments show up in the assets column under such headings as tangible and intangible fixed assets, securities, and cash and deposits. We should note in this connection that Japanese companies’ holdings of securities have increased by about the same amount as their retained earnings in the last 20 years, reflecting spending on M&As and overseas subsidiaries.

In contemplating a new tax on retained earnings, we need to keep in mind, first of all, that this money has already been taxed once as net income. A retained-earnings tax thus amounts to double taxation, something that is frowned on in principle.

As for the effect of such a tax on corporate behavior, we should consider the example of South Korea, which has actually tried a retained-earnings tax. In 2015, spurred by similar concerns over corporate “hoarding” amid wage stagnation and slow economic growth, South Korea enacted the Corporate Income Feedback Tax. Targeting companies over a certain size, the CIFT was essentially a tax penalty that was set to expire after three years. If target companies used less than 80% of their after-tax profits for investments, wage increases, and dividends in any given accounting period, then the unused “excess” was subject to a 10% surtax. About one-third of the 3,000 companies within the law’s scope ended up owing extra taxes.

The hope of the tax’s proponents was that it would induce companies to plow their profits into wage hikes (which would spur growth through consumer spending) and capital investment (which would strengthen the competitiveness of South Korean industry). But this was not the outcome. It turns out that businesses need a degree of confidence in the economy’s long-term prospects in order to raise wages and invest in fixed assets. Lacking that confidence, many South Korean firms chose instead to boost shareholder dividends to reduce their retained earnings and avoid the CIFT. Moreover, because corporate shareholders—including foreign companies—account for about 80% of the shares on the South Korean stock market, a significant portion of those dividends flowed overseas.

As the foregoing suggests, a retained-earnings tax raises problems both from a theoretical perspective and from the standpoint of efficacy.

Taxing Liquid Assets

Some have suggested that the focus of taxation should be, more narrowly, on the “cash and deposits” entry in the assets section of the corporate balance sheet. For example, perhaps the tax code could be tweaked in such a way as to penalize unreasonable increases in companies’ cash holdings.

As noted above, large Japanese companies’ cash and deposits have increased by about ¥42 trillion over the past 20 years, prompting some to accuse them of hoarding their profits. It could be argued in big business’s defense that, as a share of total corporate assets, cash and deposits have remained more or less steady at around 7%. Some have also noted that, taken together, the cash and deposits of large companies and SMEs combined (about ¥210 trillion) amount to only about 1.7 months’ worth of sales, and that, on average, this represents a reasonable amount of cash for a company to keep on hand as working capital.

It is true that companies need to keep one to two months’ worth of sales on hand as working capital to insure against short-term cash-flow problems. But the averages cited obscure the fact that some of Japan’s top corporations have squirreled away more than a year’s worth of sales while stinting on pay raises and investments. When corporations neglect their basic responsibilities to society, taxation can be viewed as a legitimate tool for modifying their behavior

Designing and implementing such a tax could be tricky and costly, however. Defining the acceptable level of cash assets for any given sector and industry would be one challenge. Another would be coming up with ways to prevent companies from converting their cash and deposits into stocks and bonds to avoid taxation. All of this could turn tax assessment into an administrative nightmare.

Liberal Democratic Party politician Sanae Takaichi, now chair of the ruling party’s Policy Research Council, discusses a possible alternative in her book Utsukushiku, tsuyoku, seicho suru kuni e (Toward a Beautiful, Strong, Growing Country). Instead of levying a surtax, she suggests imposing a flat 25% corporate income tax on businesses and eliminating all breaks except one: a 5% rate reduction for companies that raise wages by at least 5%.

Stock Buybacks and Dividends

Soaring dividends are another source of dissatisfaction with companies’ distribution of profits. Although Japanese corporations have been criticized in the past for their relatively low payouts to shareholders, some experts now believe that the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction. Professor Tomo Suzuki of Waseda University’s School of Commerce has called for a shift in management policies, arguing that the rapid regulatory reforms of the post-bubble era have opened the way for the excessive use of stock buybacks as a means of boosting share prices and dividends. Suzuki calls on Japanese corporations to reduce their ratio of dividends to equity capital and divert a greater share of their earnings to wage increases, research and development, and so forth.

In the United States, there are legislative moves afoot to address similar concerns. In September last year, Democratic Senators Ron Wyden and Sherrod Brown (chairmen of the Finance and Banking committees, respectively) unveiled legislation that would assess a 2% tax on the money corporations spend buying back their own stock. “Rather than investing in their workers, mega-corporations used the windfall from Republicans’ 2017 tax cuts to juice their stock prices and reward their wealthiest investors and their executives through massive stock buybacks,” Wyden explained in a statement announcing the initiative.

Incentivizing Good Behavior

Now, let us consider a fundamentally different strategy. Instead of using taxes to coerce companies into changing their behavior—in the manner of the North Wind in Aesop’s fable—perhaps we could create a climate conducive to the kind of corporate behavior we seek, similar to Aesop’s Sun. What might this entail in terms of concrete policy goals and measures?

First, we need an economic environment in which businesses will feel motivated to share and invest their profits with an eye to the future. The government can help create such an environment by using deregulation to encourage the expansion of growth industries and by providing financial support for green innovation and digital transformation.

Second, productivity gains are needed to sustain wage increases. The government should pursue policies to boost spending on productivity, including investments in education to build human capital. A number of targeted tax breaks have already been introduced with this in mind. (See my Making the New Capitalism a Reality: Hints from Britain’s Third Way.)

The markets can also influence corporate behavior with the aid of such government guidelines as the Stewardship Code and the Corporate Governance Code. A growing number of asset managers in Japan and around the world have begun to apply ESG (environmental, social, and governance) criteria in their investment decisions, and employee pay has recently emerged as an indicator of sustainability and social responsibility.

Prime Minister Kishida has suggested that the distribution of corporate profits through wage increases should be treated not as a business cost but as an investment that lays the foundation for further value creation. For this reason, he argues that nonfinancial reporting should include disclosures on the value of companies’ human capital, appropriately visualized.

Professor Tsutomu Watanabe of the University of Tokyo offers another perspective on the issue of wage stagnation. Watanabe points out that the Japanese public has become intolerant of price increases, regardless of the reason, so companies are reluctant to pass on even unavoidable cost increases to consumers. To maintain their profit margins, they instead feel compelled to compensate for such increases by holding down wages.

Watanabe argues that it is only natural for companies to adjust their prices to reflect the rising cost of materials and fuel, and that consumers must accept such “fair pricing” as a prerequisite for wage increases. Watanabe is hopeful that the cost-push inflation that has hit Japan as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic will jolt Japanese consumers out of their deflationary mind-set, setting the stage for sustained wage increases.

Of course, inflation alone is unlikely to jump-start the virtuous cycle envisioned by Kishida and his policy team. But Watanabe’s thesis serves to remind us that it will take a concerted effort by industry, government, and the public to break free from established patterns and usher in the new capitalism.